March 13, 2014

Driving home from her second shift at Ev’s Eleventh Hour Tavern, it is just after 3 a.m. She is returning to her girlfriend Mary Ann, on the first anniversary of their decision to become “roommates.” Her parents—despite their kindness to Mary Ann over the holidays—don’t approve. Her father won’t set foot in their Austin Street apartment.

There’s no street parking to be had, so she pulls into the Long Island Rail Road lot next to her building. Not much commuter traffic at this hour. She kills the ignition and steps out of her red Fiat. It’s a safe neighborhood, quiet except for the train and the occasional Q10 bus during the day; people keep their doors unlocked, that kind of thing. But she must see the man at the far end of the parking lot, because something is wrong. Somehow she knows. Maybe he already has out his knife.

Her apartment is around back, but she runs toward the light on Austin Street, uphill toward Lefferts Boulevard and a local bar. She doesn’t know that the new bartender closed early tonight. The block is quiet. Across the street are the Mowbray Apartments, nine stories of windows looking down on her. He’s chasing her now. The sidewalks have been icy off and on for weeks, and she makes it as far as the street lamp. She screams for help, and screams again as he stabs her. She keeps screaming. Eventually a voice comes down from the Mowbray: “Leave that girl alone!”

Her attacker looks up at the sound. He leaves reluctantly, but not before his knife has punctured a lung—the wound that will kill her. She half-crawls to her feet, stooped over, and starts around the building to her apartment. She’s alone. No one is coming. She makes it around back, out of sight, but she won’t make it any farther. She opens the closest door, the stairwell to a friend’s apartment, and collapses.

But she is still alive when her attacker returns, and without air she screams again for help.

STANDING ON AUSTIN STREET 50 years later, it is easy to replay the whole thing, at least what we know of it. Her two-story building still stands next to the Long Island Rail Road station. The Mowbray Apartments continue to tower over them both. The bookstore by the lamppost now sells comic books, and the light itself is brighter thanks to Mayor John Lindsay, fulfilling a campaign promise he made right here after the murder. Stand on this block long enough, and the Q10 still comes through on its way to JFK Airport.

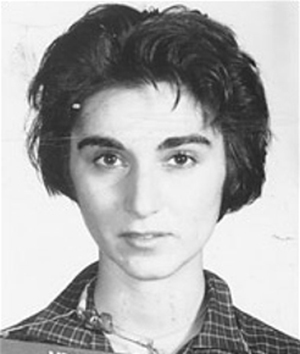

For two weeks, Catherine Genovese’s murder at the hands of Winston Moseley received little attention. It surprised people, certainly—an intensely violent crime in a safe part of Queens—but it was hardly yet one of the crimes of the century. On March 27, on a tip from police commissioner Michael Murphy, the New York Timespublished the A1 story that made Kitty Genovese a household name: “For more than half an hour,” read Martin Gansburg’s famous lede, “38 respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens.”

The number 38 is contested (and it’s generally accepted that there were two attacks, not three), but Gansburg’s lede is still ubiquitous, generating thousands of Google results today.

Just as famous is the explanation given by Genovese’s friend and neighbor Karl Ross: “I didn’t want to get involved,” he said.

In the press over the next weeks, Kitty Genovese became the victim not of her knife-wielding killer but of the apathy of her half-awake neighbors. They hadn’t called the cops, let alone intervened, and almost everything—city living, moral decline, fear of the police, the numbing effects of television—was to blame. For the rest of 1964, as Kevin Cook writes in a new book, Genovese’s screams for help appeared in “newspapers, magazines, television and radio editorials, Sunday sermons, dinner-party conversations, schoolyard rumors, and back-fence gossip.”

In the years that followed, her murder inspired a song by folksinger Phil Ochs, episodes of Perry Mason and Law & Order three decades apart, a Harlan Ellison short story, a History Channel documentary, a chapter in Malcolm Gladwell’s Tipping Point, and another in Superfreakonomics. The Genovese case accelerated the implementation of the 911 emergency system. It led to a golden era in social psychology—from the discovery of the bystander effect (people are more likely to intervene when there are no other onlookers) to dozens of experiments on empathy and samaritanism.

“The case touched on a fundamental issue of the human condition, our primordial nightmare,” said Stanley Milgram, whose work on obedience and responsibility won him the AAAS Prize for Behavioral Science Research the same year, at a conference two decades after the murder. “If we need help, will those around us stand around and let us be destroyed or will they come to our aid?”

Now, on the murder’s 50th anniversary, two new books offer the definitive account: Kevin Cook’s Kitty Genovese: The Murders, the Bystanders, the Crime That Changed America, quoted above, and Catherine Pelonero’s Kitty Genovese: A True Account of a Public Murder and Its Private Consequences.

Comparisons between the two seem all but inevitable. For Cook, this book adds to a long list of non-fiction works, including a history of the 1970s NFL and a biography of gambler Titanic Thompson; Pelonero, in contrast, is a playwright by trade, and this uncharacteristic project feels like the culmination of a particular, long-time fascination with Genovese. In this light, the books’ differences make sense. While Pelonero seemingly draws on deeper, longer, more obsessive document research, Cook organizes what he has into a smoother narrative. Sometimes the context he provides tends toward fluff (Kitty and Mary Ann’s occasional trips to Greenwich Village become a digression on Bob Dylan and Dave Van Ronk, for instance), but his storytelling is a welcome change from the second half of Pelonero’s book, which descends into newspaper block quotes and long chapters of court transcripts.

IF YOU READ EITHER Kitty Genovese, you’ll find that it clarifies what happened quite nicely. But if you read both, you may find yourself more confused than before. Was Mowbray resident Greta Schwartz a side character who placed a concerned phone call to a neighbor (Cook) or was she the woman who found Genovese’s body (Pelonero)? Was the bar on the corner called Bailey’s Pub (Cook) or the Austin Bar & Grill (Pelonero)? Did the police initially suspect Kitty’s girlfriend Mary Ann or their friend Karl Ross? Did Alphonso Moseley, the man who raised Winston Moseley, give Winston a gun in 1963 or did he keep it himself? Was Winston’s wife named Betty or Bettye?

Cook and Pelonero also disagree on the central historical controversy of that early morning in Kew Gardens: How many witnesses were there? Cook, building on a three-decade trend toward Genovese revisionism, argues convincingly that there were only a handful who knew what was happening, far short of the infamous 38. Others were asleep; or they mistook her screams for a drunken argument; or they watched her stand up and walk out of sight, not realizing that they had witnessed a stabbing. Pelonero, meanwhile, stands by Gansburg’s number. No one since has investigated as thoroughly as the Times reporter, Pelonero says (even as she repeatedly corrects Gansburg’s claim that there were three attacks), and too much time has passed to know otherwise. According to Pelonero, the revisionists, drawing on assertions by a handful of Kew Gardens residents, have simply outlived the detectives and newspaper reporters who knew better.

Try on either of these arguments for size, and it sounds reasonable. What’s harder to explain is why the dispute over numbers matters. Were there more than 38 people within earshot of the first attack? Yes. Did 38 of them know what they were witnessing? Almost certainly not. Was the New York Times story geared toward sensationalism? Absolutely. But even in Cook’s conservative assessment, there were two men who were watching and chose not to intervene, and at least four or five other neighbors who were awake and had a pretty good idea. If the story of Kitty Genovese is that her neighbors did nothing while she was murdered, it is not an “intractable urban myth,” as a paper in American Psychologist described it in 2007. There were witnesses, and no one helped her. That’s no urban legend.

KITTY GENOVESE DIDN’T CARE for fiction. Cook quotes the explanation she gave Mary Ann: “I like what’s real.” Yet her story, used so often to demonstrate the bystander effect, illustrates another, equally interesting psychological phenomenon: the surprising fallibility of memory.

Research on eyewitness testimony has revealed that even our sincere, sworn statements often misrepresent what happened. However static and objective they feel, our memories are the ever-changing product of a subjective mind. Sometimes our biases and assumptions color our perception, and sometimes we simply make mistakes; all told, we’re just not very good at recounting events accurately. And time compounds these errors: Each time we call up and review a memory, we refine it, make it cohere with other narratives, and gradually reshape our own history. When we remember, we are actually recalling what Barbara Tversky calls “memories of memories.” Separate two witnesses for 50 years, and, like a game of telephone, enough small changes will accrue to give you two very different stories.

“People are never surprised when they forget things that happened but are always surprised when they remember things that didn’t happen,” says Tversky, professor at Columbia, professor emeritus at Stanford, and one of the world’s foremost cognitive psychologists. “We are constantly rewriting our memories in light of the present. The residents have one narrative they want to tell, and the police have a different narrative. It’s storytelling: what you think is interesting and what you’re being called on to tell.”

If you read the Cook and Pelonero books back to back, you almost can’t help but notice the discrepancies. Their interviews make a Venn diagram: There are the people they both talked to, who have their stories set after 50 years and provided nearly identical details, and then there are those who spoke to only one author, who send the books in disparate, sometimes contradictory directions—not only in their conclusions about the number of bystanders, but in the basic facts of what occurred. (Ten years after the murder, to take another example, Martin Gansburg was still citing eyewitnesses to say that Moseley attacked Genovese three times, when all forensic evidence pointed to twice.)

Fifty years later, do we have any chance of knowing just what transpired on Austin Street? So many questions—how many witnesses were there; what did they see; where was Greta Schwartz; who, if anyone, suspected Mary Ann or Karl Ross—were difficult in 1964 and seem nearly impossible now. “History,” Tversky says, “is so much based on people’s memories and diaries and written accounts, and you know those accounts have flaws in them. Ultimately, memories don’t have the form of words. They don’t come with interpretations. We impose all that at the time something is happening.”

Which raises another question: Why are we so insistent on piecing it together? What part of human nature so obsesses us with historical details, lingering mysteries, true crimes? We know the broad outlines of Kitty Genovese’s murder, and we have years of social science to teach us the morals of the story, yet every decade sees new books and new articles in the Times and American Psychologist, and recently in the New York Post and the New Yorker, reconstructing and debating the final 30 minutes of her life. It’s addicting, I can testify—reading old newspapers, traveling to Kew Gardens, retracing her steps, weighing one possibility against another.

Cook and Pelonero try to balance this morbid fascination with humanizing portraits of Kitty Genovese, the person. Cook promises “to show that Kitty Genovese was more than a name in a newspaper.” He succeeds, drawing upon long interviews with Mary Ann to provide a charming sketch and a sense of the heartbreaking discrimination faced by a gay couple in 1964, even in New York City. But isn’t this odd as well, delving as a public into the intimacies of one unsuspecting person’s life? And to interview Mary Ann again and again about the most painful episode in her life… for what? It’s disconcerting that something so involuntary as being murdered turns you, your partner, and your family into the subjects of five decades of investigation and public biography.

When I saw that Mary Ann had opened up to the press in 2004, 40 years after the murder, and had since been interviewed a number of times, it seemed only natural to approach her. Almost every interview came with disclaimers about how painful she still finds the topic, but they gave me little pause. She had accepted the interviews, after all, and 50 years is a long time. So I called her.

We had an intense 10-minute conversation, a choppy, uneven one in which I never got to my questions. We talked mostly about her willingness to be interviewed. She seems motivated by a sense of duty, that telling and retelling Kitty’s story might motivate some future bystander to act. “Maybe it will help save some lives or help some people,” she says, speaking slowly. “I believe that people should help each other instead of watching. The human condition seems to be to observe and not to do anything.”

I’ll leave that as Mary Ann’s message 50 years after her tragedy, and only say that, after hanging up, I wished I had left her alone.