(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Oral arguments began this week in a religious freedom lawsuit brought by the Satanic Temple that challenges Missouri’s abortion restrictions. The lawsuit argues that the state’s law requiring “‘informed consent’ materials, ultrasound, and [a] 72-hour waiting period” for women who request an abortion impedes the religious freedom of Satanic Temple members.

In 2015, a member of the Temple drove three hours to the nearest Planned Parenthood seeking an abortion, and was told that the law required her to review an informational booklet and wait 72 hours before ending her pregnancy. Owing to the fact that the inviolability of one’s own bodily autonomy is among the church’s central tenets, the lawsuit argues that these restrictions forced the woman to violate her will for her body—namely, her desire to have the abortion she wanted, immediately and without state interference.

While this argument might sound more sophistic than sophisticated, the United States has a rich history of religious exemptions to law. Perhaps unsurprising for a country with origins as a sanctuary for religious persecution, loopholes for religious belief are as old as our laws. Still, it hasn’t been a straightforward path from those founding ideals to the religious exemptions the Satanic Temple argues its members deserve. Centuries of legislation, court rulings, religious discrimination, and religious liberation all culminate in the Temple’s curious argument. An examination of that history shows the separation of church and state to be … actually rather confusing.

Atheists in the Foxholes

(Illustration: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

One of the oldest and most familiar belief-related exemptions to U.S. law is that of the “conscientious objector,” which dates back to the Revolutionary War—at least for the rich. When George Washington asked for a military draft, he called for exempting “those with conscientious scruples against war.” Laws varied by colony, but many conscientious objectors could pay a fine equal to the salary that would have been earned through service. However, in Pennsylvania, Quakers who objected to the fees were forced to pay for their beliefs with their property and their freedom. Some of these Quakers were imprisoned for as long as two years, and, overall, hundreds of thousands of pounds of Quaker property was seized in retaliation for principled pacifism.

When Congress instituted peacetime conscription in 1940, it stipulated that draftees “conscientiously opposed to participation in war in any form” for religious reasons could choose an alternative service “of national importance.” A few decades later, during the Vietnam War, many Seventh Day Adventist draftees were funneled into Operation Whitecoat, a controversial biodefense project in which participants were infected with various strains of bacteria that the military feared could be used by the Soviets as a biological weapon. The Adventists endured yellow fever, hepatitis A, Q fever, equine encephalitis, and many more diseases. Though none of the soldiers died during Operation Whitecoat, U.S. Army colonel Philip Pittman told PBS that a study done in the early 2000s showed increased rates of asthma and headaches among participants, even decades later.

An Old Wives’ Tale

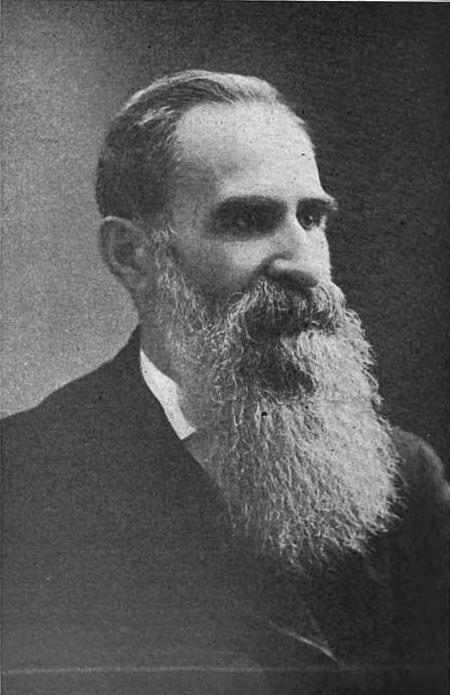

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

One of the earliest Supreme Court cases that ruled on religious exemption was centered around bigamy, the possession of multiple wives. The court’s opinion in the case, Reynolds v. United States, was resolutely unfavorable to belief-based law-skirting, though it later played an important (if indirect) role in the creation of legislation supporting these kind of exemptions. Reynolds emerged from the mid-19th century conflict between the Mormon church and the government over the practice of bigamy, which was banned by federal law. George Reynolds, a prominent LDS Church member and secretary to Brigham Young, turned himself in to be arrested after he married his second wife in Utah territory in 1874, as part of the church’s plan to challenge the constitutionality of the anti-bigamy law. Following his conviction 1875, Reynolds sued the state, arguing that his First Amendment-guaranteed freedom of religion had been violated. Bigamy was a fundamental practice of his Mormonism, he and the church argued.

Finding this argument unconvincing, the Supreme Court ruled that Mormons were not exempt from anti-bigamy laws. The court concluded that the establishment clause forbids only the legislation of opinion, not behavior. An 1879 article in the New York Times admitted that the law was intended to target Mormons, but praised the decision as necessary to prevent legal exemptions for a possible “sect which should pretend, or believe, that incest, infanticide, or murder was a divinely appointed ordinance.” Religion in the U.S., it would appear, was to be subservient to law. At least, for a time.

A Long, Strange Trip

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Though Reynolds primarily concerns the marriage practices of 19th-century Mormons, it returned to center stage more than a century later in another fight between law and religious practice. This time, the bone of contention was the use of psychedelic drugs in the long-marginalized Native-American community. In 1983, two members of the Native American Church were fired from their jobs at a drug rehab facility in Oregon after testing positive for peyote, which they used in church rituals. Because they had been fired for illegal drug usage, their subsequent filing for unemployment benefits was denied by the state.

A series of appeals led the case, Employment Division v. Smith, to the Supreme Court, which ruled in 1990 that, since the general ban on peyote did not specifically target Native American Church members, it did not violate the religious freedom guaranteed by the First Amendment. To justify the burden that the peyote ban put on members of the Native American Church, the government needed only to prove it had a compelling interest in doing so. Justice Anthony Scalia authored an opinion that relied heavily on Reynolds in its assertion of law over religious practice. The opinion also re-asserted the illegality of laws directed at specific religious groups—an irony, given that the case providing grounds for the ruling was so rooted in anti-Mormonism.

Legislative Loophole as Religious Remedy

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The ruling in the peyote case was wildly unpopular. Progressives feared that the decision could provide grounds for the oppression of minority groups, such as the Native Americans in Smith. Unsurprisingly, religious groups across the ideological spectrum were dissatisfied with the ruling, and heavily lobbied Congress to overturn the ruling with legislation. This led to the passage of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which President Bill Clinton signed into law in 1993. RFRA codified religious exemptions to federal laws, except in special cases that meet “strict scrutiny,” the most stringent standard of judicial review.

Speaking at the bill signing, then-Vice President Al Gore presented the bill as doing uncontroversial things like preserving the architectural autonomy of the good congregations of America. “Those who want churches close to where they live have seen churches zoned out of residential areas,” Gore said. “Those who want the freedom to design their churches have seen local governments dictate the configuration of their building.” At last, these small indignities would be remedied. Who could object? Few in Congress, to be sure. The bill passed 97–3, ushered through the chambers by bipartisan co-sponsors such as Chuck Schumer (D-New York) and Orrin Hatch (R-Utah).

Hobby Horse, Unhobbled

(Photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

However, intentionally or not, the RFRA would become a broadly influential law, with wide-ranging implications. Two decades later, it would provide the basis for a chain of arts and crafts stores’ challenge to an Affordable Care Act provision requiring employer health insurance to cover contraceptives like IUDs and the morning after pill. The chain of stores, Hobby Lobby, is owned by a family of evangelical Christians who devote significant portions of their profits to the furtherance of Christianity. “We want to share this book with people all over the world,” Steve Green, one of the family members behind Hobby Lobby, told The Atlantic. “And the more resources we have, the more we’re able to do that.”

Hobby Lobby filed a lawsuit against the enforcement of the contraception rule in 2012, arguing that the rule forces the owners of Hobby Lobby to violate their religious beliefs. The company argued that RFRA made clear their right to religious exemption from such a requirement, despite the fact that the law was written with people—not corporations—in mind. However, in 2014, (with a district court decision from future Supreme Court member Neil Gorsuch along the way) the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Hobby Lobby. Under RFRA, the opinion concludes, even corporations are worthy of exemptions to laws based on religious beliefs.

States Rights!

(Photo: Marc Piscotty/Getty Images)

But the RFRA reign has not been limited to federal law. Since 1993, 21 states have enacted their own state Religious Freedom Restoration Acts (including Missouri, whose RFRA is the basis for the Satanic Temple’s lawsuit). In states such as Indiana and Arkansas, RFRAs were passed in apparent response to the nationwide legalization of gay marriage. “It is vitally important to protect religious freedom in Indiana,” Eric Miller, a conservative lobbyist, said. “In order to help protect churches, Christian businesses and individuals from those who want to punish them because of their Biblical beliefs!”

But Indiana’s RFRA might protect more than just Christian businesses. Later this fall, the First Church of Cannabis will argue in Indiana state court that Indiana’s RFRA allows them a religious exemption to the state’s strict marijuana laws. “I don’t think they deserve the finger,” the church’s leader, Bill Levin, told the Indianapolis Star, when asked if his church was intended as a figurative middle finger to the state legislature. “I think they deserve gratitude. They helped clear the pathway to a bright, new, exciting religion that’s going to dominate the world.”

It remains to be seen whether the First Church of Cannabis will, in fact, dominate the world, but it’s undeniable that, in the U.S., religious exemptions keep a significant check on governmental authority. The RFRA permits corporations to shirk their federally mandated health-care obligations via religious objection; 47 states and Washington, D.C., explicitly permit children to remain unvaccinated for reasons of belief; and—surely to the chagrin of many religious lawmakers throughout our history—a Satanic church may have legitimate claim to religious exemption for a state law. Perhaps the implication of the Satanic Temple’s lawsuit is: If you think our religious exemption is absurd, look in the mirror.