George Nickel was on the last can of a case of beer when it dawned on him that his dachshund was missing. He’d been drinking a lot since coming back from the military hospital to his home in Boise, Idaho. That was understandable. His tour in Iraq as a U.S. Army combat engineer had ended with a roadside bomb attack that killed the rest of the crew on his armored vehicle and landed him in the hospital for 11 months. To top it off, his wife, an army sergeant, was away in Texas awaiting her own deployment to Iraq. Nickel insisted to his friends that he was fine, but he knew he wasn’t. By that July night in 2009, he hadn’t slept in three days.

He had to go find his dog, he decided. Through the slurry of his thoughts, his army experience kicked in. Nickel suited up like he had for all those patrols in Falluja and Ramadi. He slipped on his tactical vest, holstered his pistol, and slung on his AR-15 rifle.

Nickel climbed the stairs to the apartment above his, shot two bullets into the lock, and kicked in the door. No one was inside. Across the hall, he heard a woman screaming.

“I want my dog back,” yelled Nickel.

“I don’t have your dog,” the woman shrieked.

Nickel shot the woman’s door lock off. But before he could move inside, he heard shouting and saw lights from the parking lot below. He stepped onto the landing to see 11 men piling out of their cars. Nickel drew his pistol and pointed the flashlight attached to its frame at them, hoping to see them better.

Big mistake. The men in the parking lot were cops, and they opened fire. Nickel dove for cover as at least a dozen bullets slammed into the wall where he had just been standing. It was only at that moment, he says, that he realized the men were police.

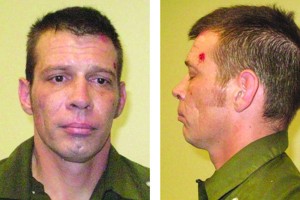

U.S. serviceman George Nickel

Nickel surrendered. After months in jail, he wound up in a Veterans Health Administration hospital, diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and a traumatic brain injury from the blast in Iraq.

Dramatic as it was, Nickel’s arrest was far from an isolated case. As American soldiers stream back from Iraq and Afghanistan, many of them are running into serious troubles with police. The FBI is called in to about 20 hostage situations involving veterans each year, and police report many more dangerous confrontations. As many as 20 percent of America’s hundreds of thousands of Iraq and Afghanistan vets may be, like Nickel, battling PTSD, brain injuries, or other mental health problems. Many also struggle with unemployment and substance abuse issues. Those factors make legal problems more likely. A recent survey by researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill of 1,388 Iraq and Afghanistan vets found that those with PTSD and high irritability were more than twice as likely to have been arrested as other veterans; those abusing substances were more than three times as likely.

Vietnam taught us how often soldiers traumatized by conflict overseas can wind up in trouble with the law back home. As of 1988, almost half of all male Vietnam War combat veterans with PTSD had been arrested or jailed at least once, according to a study by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

This time around, though, a growing array of police, court, and correctional officials are trying to help. The federal government has hired more than 200 outreach workers to help connect veterans with legal services, and has doled out over $20 million in grants to special courts and other programs helping veterans in the criminal justice system.

The Department of Justice is also funding a program to train police in 15 towns and cities in veterans’ issues. In Maine, after four fatal standoffs between police and veterans, a county sheriff launched a de-escalation seminar open to any cop in the state.

“It’s so different from Vietnam, when we all got drafted. Now, many officers haven’t served,” says Wayne Shellum, a retired police chief who is leading the Justice Department–funded training sessions. Treating a traumatized vet the same way you’d treat any other troublemaker, says Shellum, “could cost you your life.”

But many law enforcement officials don’t think such special treatment is warranted. In California, bills to create veterans’ courts statewide have been defeated several times in recent years.

“There are a lot of defendants who will use PTSD as a defense. Does it matter what caused the PTSD? I’m not sure it does to the victims,” says Scott Thorpe, head of the California District Attorneys Association, which lobbied against the bills. California, he adds, already has “too many specialty courts. It draws unfairly on the resources of the criminal justice system.”

Nickel was eventually put on probation that included substance abuse and mental health counseling. “All this has made me realize how crazy it was that I told myself to suck up my problems and drive on” after returning from Iraq, he says.

Now, he volunteers with the local veterans’ court. He has also worked with Boise Police Chief Mike Masterson to help teach officers how to de-escalate conflicts with troubled veterans. Masterson says that training has helped save lives in dozens of incidents already.

“If we don’t take care of these folks,” says Masterson, “what message does it send when we ask the next generation to go to war?”