The Marysville Pilchuck High School shooting in Washington on Friday was the 39th school shooting in the U.S. this year. Most of those got little press coverage. Unless someone is actually killed, a shooting might not even get coverage in the local news.

Friday’s did.

Why would an apparently happy kid shoot several classmates? That seems to be the question that’s getting the attention of the press and perhaps the public. “Struggling to Find Motive,” said one typical headline. That’s the way we think about school shootings these days.

Asking how a 14-year-old got a handgun is like asking how he got a bicycle to ride to school.

It’s unlikely that any of the motives that turn up will be all that strange. Freshman student Jaylen Fryberg may have been upset by a racial comment someone had made the day before or by a break-up with a girl. He may have had other conflicts with other kids. Nothing unusual there.

But “why” is not the question that first occurs to me. What I always ask is how a 14-year-old kid can get his hands on a .40 Beretta handgun (or whatever the weaponry in the shooting of the week is). For Fryberg it was easy. The pistol belonged to his father. Nothing strange there either. Thirty million homes in the United States, maybe 40 million, are estimated to be stocked with guns.

Do European countries have school shootings like this? Surely kids in Europe get upset about break-ups; surely they must have conflicts with their classmates; and surely, some of them may become irrationally upset by these setbacks. So surely there must have been school shootings in Europe too.

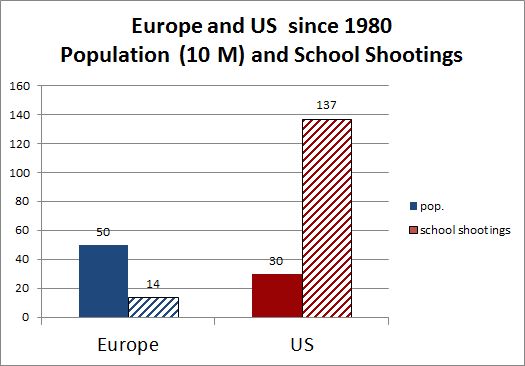

I went to Wikipedia and looked for school shootings since 1980 (here and here). I eliminated shootings by adults (e.g., Adam Lanza in Sandy Hook, Anders Brevik in Norway). I also deleted in-school suicides even though these were done with guns and were terrifying to the other students. Of course, my methods are not fast, and not perfectly accurate, and the population estimate in the graph below is based on current numbers; I didn’t bother to find an average over the last 35 years. Still, the differences are so large that I’m sure they are not due to technical problems in the data.

Does the U.S. have a much greater proportion of kids who are mentally unstable? Do our schools have more bullying? Are European kids more capable in dealing with conflicts? Are they more stable after break-ups? Do they spend less time with violent video games? Do their schools have more programs to identify and counsel the potentially violent? I’m not familiar with the data on these, but I would guess that the answer is no and that our kids are no more screwed up than kids in Europe. Or if there are differences, they are not large enough to explain the difference in the body count.

No, the important difference seems to be the guns. But guns have become the elephant in the room that nobody talks about. Even asking about access to guns seems un-American these days. Thanks to the successful efforts of the National Rifle Association and their representatives in government, guns have become a taken-for-granted part of the landscape. Asking how a 14-year-old got a handgun is like asking how he got a bicycle to ride to school.

When the elephant’s presence is too massive not be noticed—for example, when the elephant kills several people—the elephant’s spokesmen rush in to tell us that “No, this is not the time to talk about the elephant.” And so we talk about video games and psychological screening and parents and everything else, until the next multiple killing. But of course that, too, is not the time to talk about elephants.

This post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “School Shootings: What’s Different About Europe?.”