In 2006, I set out to investigate the history of what had really happened with Northwestern psychology researcher Michael Bailey and his transgender critics. I thought I knew from my background in science studies and a decade of intersex patient-rights work how to navigate an identity politics minefield—but the results shocked me. Letting the data lead me, I uncovered a story that upended the simple narrative of power and oppression to which we leftist science studies scholars had become accustomed.

I found that, in the Bailey case, a small group had tried to bury a politically challenging scientific theory by killing the messenger. In the process of doing so, these critics, rather than restrict themselves to the argument over the ideas, had charged Bailey with a whole host of serious crimes, including abusing the rights of subjects, having sex with a transsexual research subject, and making up data. The individuals making these charges—a trio of powerful transgender women, two of them situated in the safe house of liberal academia—had nearly ruined Bailey’s reputation and his life.

Science and social justice require each other to be healthy, and both are critically important to human freedom.

To do so, they had used some of the tactics we had used in the intersex rights movement: blanketing the Web to make sure they set the terms of debate, reaching out to politically sympathetic reporters to get the story into the press, doling out fresh information and new characters at a steady pace to keep the story in the media and keep the pressure on, and rhetorically tapping into parallel left-leaning stories to make casual bystanders “get it” and care. Tracking their chosen techniques was occasionally like reading a how-to activist manual that I could have written, but there was one crucial difference: What they claimed about Bailey simply wasn’t true.

You can probably guess what happens when you expose the unseemly deeds of people who fight dirty, particularly when you publish a meticulously documented journal article detailing exactly what they did, and especially when the New York Times covers what you found. Certainly I should have known what was coming—after all, I had literally written what amounted to a book on what this small group of activists had done to Bailey. But it was still pretty uncomfortable when I became the new target of their precise and unrelenting attacks. The online story soon morphed into “Alice Dreger versus the rights of sexual minorities,” and no matter how hard I tried to point people back to documentation of the truth, facts just didn’t seem to matter.

Troubled and confused by this ordeal, in 2008 I purposefully set out on a journey—or rather a series of journeys—that ended up lasting six years. During this time, I moved back and forth between camps of activists and camps of scientists, to try to understand what happens—and to figure out what should happen—when activists and scholars find themselves in conflict over critical matters of human identity. This book is the result.

It seems that, especially where questions of human identity are concerned, we’ve built up a system in which scientists and social justice advocates are fighting in ways that poison the soil on which both depend.

I understand that some people on an exploration like this might have tried to just clinically observe it all and to write an “objective” third-person account of scientific controversies over human identity in the Internet age. But already by the time I set out, I knew way too much about individual human bias to kid myself into thinking I could work simply as a stateless reporter above all the frays. I also felt too strongly the need to honor both good science and good activism to remain uninvolved when I saw crazy stuff happening on one side or the other. I believed—and still believe—too much in the importance of facts to sit idly by when I saw someone, be it a scientist or an activist, actively misrepresenting what is really known. As a consequence, as I traveled through scientist-activist wars over human identity—first in psychology, then anthropology, then prenatal pharmacology—rather than being merely embedded, I kept getting uncomfortably embroiled.

In spite of how difficult some of it has been, this journey of discovery proves something really important: Science and social justice require each other to be healthy, and both are critically important to human freedom. Without a just system, you cannot be free to do science, including science designed to better understand human identity; without science, and especially scientific understandings of human behaviors, you cannot know how to create a sustainably just system.

As a consequence of this trip, I have come to understand that the pursuit of evidence is probably the most pressing moral imperative of our time. All of our work as scholars, activists, and citizens of democracy depends on it. Yet it seems that, especially where questions of human identity are concerned, we’ve built up a system in which scientists and social justice advocates are fighting in ways that poison the soil on which both depend. It’s high time we think about this mess we’ve created, about what we’re doing to each other, and to democracy itself.

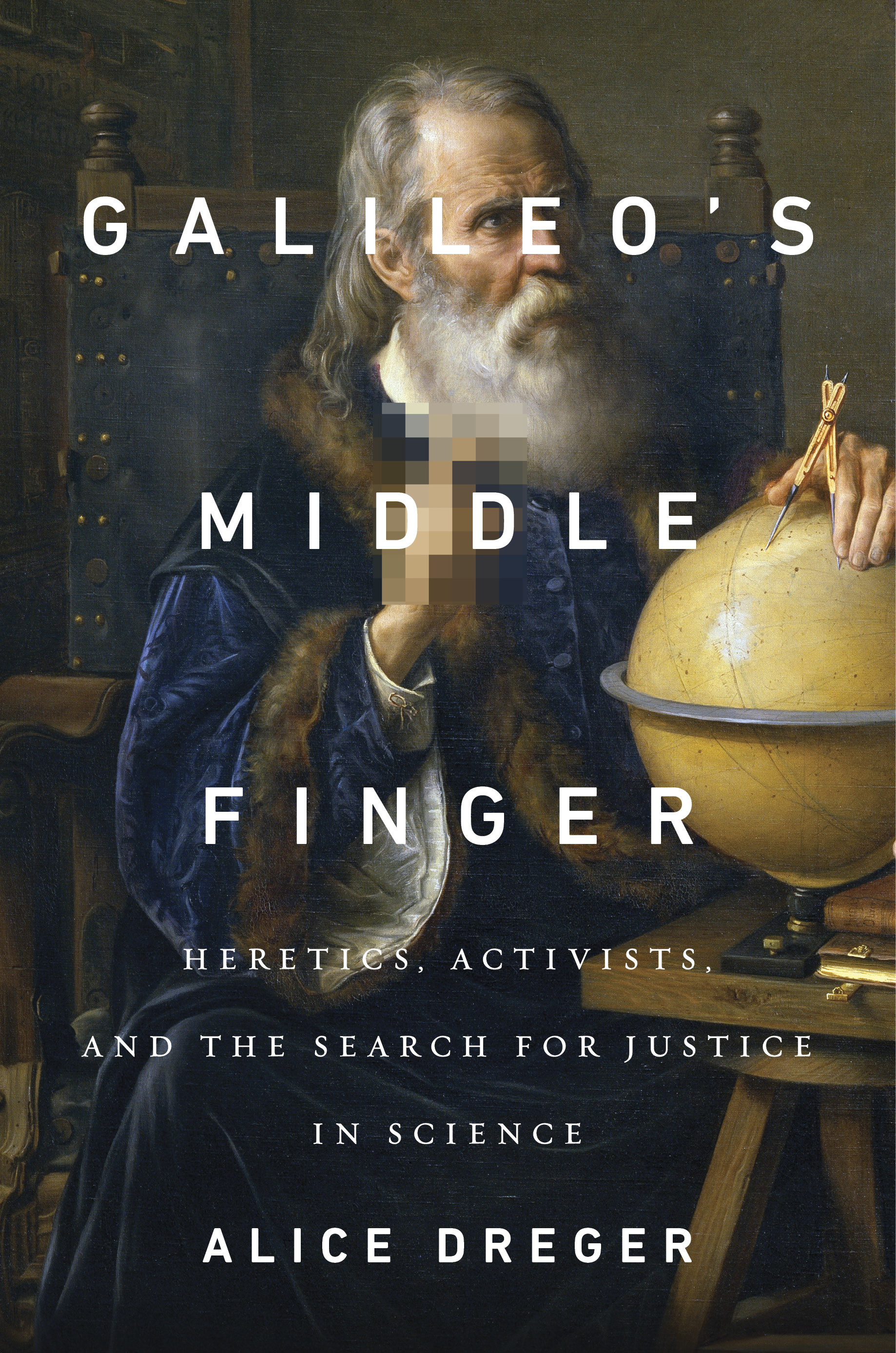

Excerpted and adapted from Galileo’s Middle Finger: Heretics, Activists, and the Search for Justice in Science by Alice Dreger, published in March 2015 by Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © Alice Dreger, 2015.