I lean back against Jim Hines’ chest as he poses, his hands on his hips and one leg propped up on a chair, as he gazes out at a small audience. “I might be bare-chested and obviously put on display for your pleasure,” he observes, but still, “strong and powerful and competent.”

“Oh Jim,” I sigh, providing the punch line.

On a ballroom stage at the Minicon science fiction convention in Minneapolis, Hines is showing a crowd of fans how he became Internet-famous. Though Hines is a respected author of speculative fiction, he’s best known for his viral collections of photographs that parody the gender tropes of fantasy and science-fiction book covers. With his photos, which he publishes on his blog, Hines poses as women to show how they are depicted on covers in physically impossible or uncomfortable positions to make them sexually appealing. At the same time, men maintain their power even when positioned as sex objects (such as in romance novels), Hines says.

To make that latter point, he needs someone to serve as the ingenue while he pretends to flex his pecs. Suddenly, the interview I’m doing with him onstage turns surprisingly interactive.

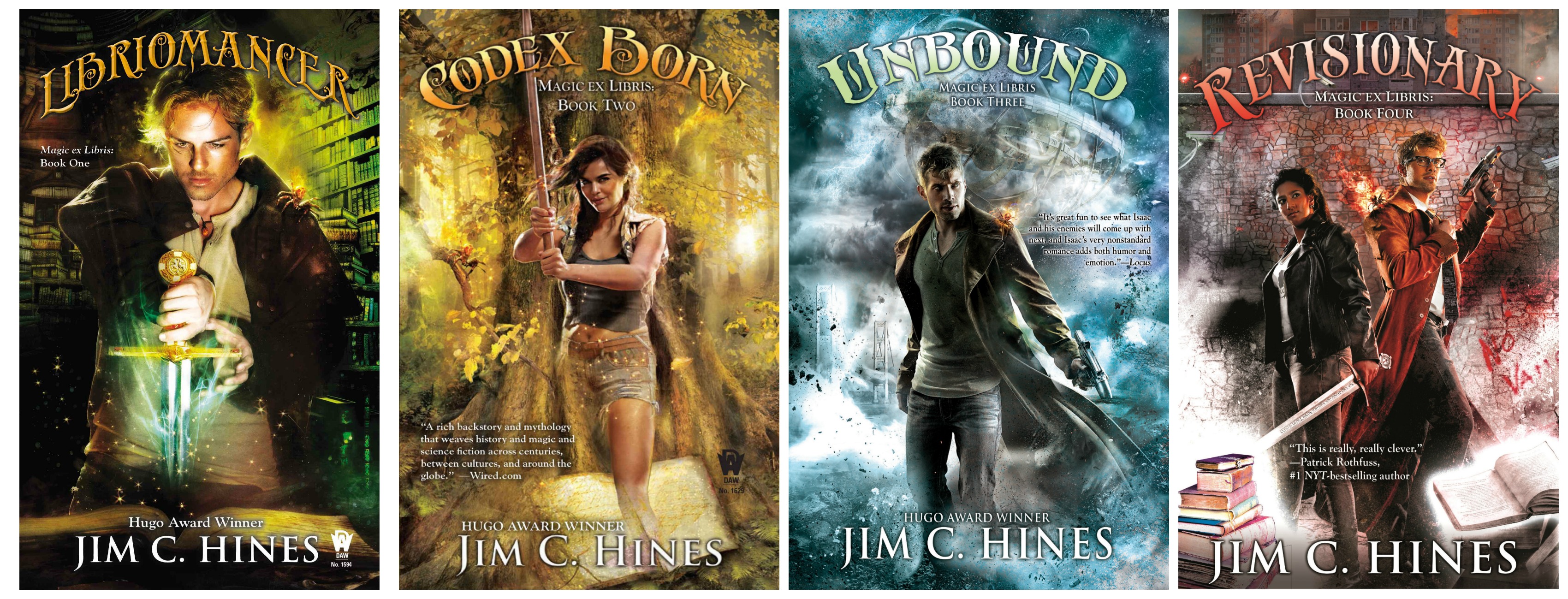

Hines pays attention to representation in his novels too. His Magic Ex Libris series, a quartet of books in which a mild-mannered Michigan librarian discovers he can pull both spells and artifacts out of his favorite works of fiction, features a depressed protagonist, an autistic major character, and storylines about the ethics of curing illness or disability through magic. (The series is also playful: Hines says that his initial goal in creating it was to kill a sparkly, Twilight-like vampire with a lightsaber.) On his blog, Hines has written transparent posts about the difficult financial aspects of writing for other prospective authors, and penned stories about managing diabetes and struggling with depression.

Overall, Hines tells me in our interview at Minicon, each step in his career has been about “trying to fix the world.” At the convention we talked about why he writes and blogs, and why one day he decided to jump in front of the camera and pretend to be a cover model.

I’ll start by asking you for your superhero origin story. How did you become a writer?

I really want to start with the whole “My planet was exploding … and my parents sent me off in a ship before being gunned down in an alley, at which point I was re-built out of clay.”[Really, though,] go back in time about 22 years, it was 1995, I was an undergraduate, and I had a friend who liked to write and he was writing these science-fiction stories and fantasy stories. I’ve always been a geek. I’m reading these stories and thinking: “Oh, this is really cool. I should try this. How hard can it be?”

How hard was it?

I have probably close to 600 rejection letters sitting in a box at my house.

A lot of people would have stopped.

I enjoyed the writing process and I sent off that first story thinking I was brilliant and [author and Sword & Sorceress publisher] Marion Zimmer Bradley said “No.” She gave me a list of her magazine’s guidelines and highlighted all of the things I had done wrong. And it hit. It was painful, but it was helpful because I didn’t make those mistakes again, I found new mistakes. Eventually, I did sell her a story for Sword & Sorceress. I’m signing the contract and it’s like, “You don’t remember me, but I remember that letter, I still have that letter.”

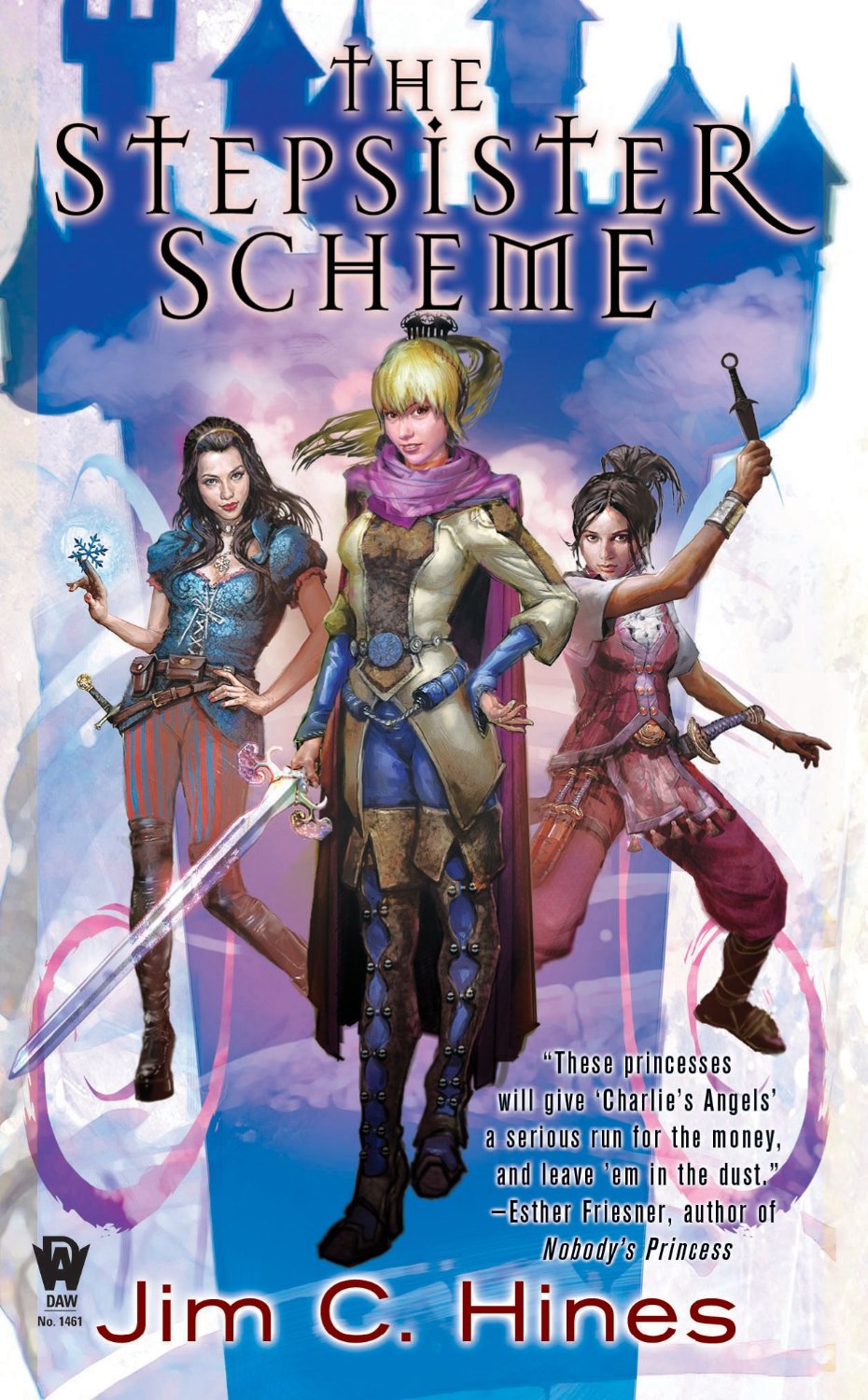

(Photo: DAW/Pacific Standard)

When did you figure out that you wanted to write about your experience of becoming a writer in your blog?

Pretty much from the beginning. It felt like there was this big, gaping, hole in a lot of areas where we talk about the business side [of writing].

And then you decided to start blogging about gender and cover art, and to take off most of your clothes and pose in really exciting ways. How did that happen?

It was around 2012, and I had been blogging for a while and some of the issues that I write about are representation, sexism, and discrimination, especially as it pertains to science-fiction/fantasy, because this is my world. One aspect of that is the portrayal of women in science-fiction/fantasy. We got some issues. And so I sat down and started writing a blog post about it making no sense that we put women in these overly sexualized poses, they’re completely impractical, and it felt boring. So I called my wife and said: “Let’s try something different. Can you take some pictures of me doing these poses?”

We started with one of my book covers, The Stepsister Scheme. It doesn’t look that bad, but then she throws her hip out a little and there it is: a back cramp, and I hadn’t gotten into the pose fully yet. My wife’s going there: “OK, twist more. Ehh, a little more.” I did not expect that [it would be so] surprisingly painful.

This is what I went viral for. If I had known that, I would have worked out a little more.

That was one of the more interesting things. The project wasn’t just about bodies being exposed, but that they’re being exposed and then put into impossible or improbable and painfully weird contortions.

I’ve got nothing [against] people taking off their clothes and showing off their bodies.

Let’s talk a little about disability, a new issue that’s been cropping up on your blog and in your fiction.

It goes back really to the same stuff I’m trying to do with everything else. Trying to fix the world.

Did you hesitate at all? What went into deciding you were going to talk about yourself as a person with disabilities?

It’s a weird thing in my head, whether or not I considered: Am I disabled? Because, generally, I don’t think of it that way. But I also got into a conversation on Twitter when we were talking about disability and somebody said, “Well, it feels like this is more of a conversation that people with disabilities should be having.” I said, “Well, I’m a Type 1 diabetic and I’m on antidepressants for my mental illness, do I count?” and we weren’t sure.

The diabetes came first. I’m trying to de-stigmatize it and to say, “Look, this is all it is.” I will check blood-sugar in the middle of panels sometimes. Partially because I need to check blood sugar and partially [to say] “Look, it’s not a big deal.” With the depression, I did think: “Is this something I want to talk about? Is this something I want to expose to people?”

It’s important to me in terms of [accepting], yes, my brain does this messed up thing with its neurochemicals, and I need to accept that and deal with it because it was messing up my life. I knew, intellectually, that I wasn’t alone, but we don’t talk about it. Depression knows those insecurities and it will tell you that you’re just weak. It tells you you’re alone and it shuts people out. Talking about it was both a way for me to tell other people with depression, “Hey, me too, fist bump,” and also to get that peace back.

There was much more of a response than I expected. Both online, [with] people commenting and saying, “Hey, thank you for this, I’ve been fighting this for a while,” or “Hey, I thought I was just weak and stressed but maybe I should talk to somebody.” I’ve had people come up to me at conventions and say, “Hey, because of that blog series you did talking about depression I went and talked to my doctor. I’m seeing a therapist now.”

Finally, let’s talk about your fiction. When you introduce magic and start talking about disability and cures, how do you tell compelling stories about health when you can wave the magic wand?

Yay, we can fix people! But why are we assuming some of these people are broken? Isaac [the Libriomancer protagonist] is depressed, clinically depressed. You know they say, “Write what you know”: I wanted to write it and portray it in a way that felt true instead of that romanticized or quick-fix story, “Oh, you are so depressed, but then this thing happens and now life is good again!” It doesn’t work that way. I was trying to make it real, so there were reasons that [the character’s depression] could not just be fixed by magic—some of which are spoilers, some of which is because depression is neurobiological, but also [because] it can be situational. I’m proud of the way I portrayed that, trying to keep that piece of Isaac’s story true.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.