Dispatcher: Which entrance is that that he’s heading towards?

Zimmerman: The back entrance… fucking punks.

Dispatcher: Are you following him?

Zimmerman: Yeah.

Dispatcher: Okay, don’t do that.

Zimmerman: Okay.

If you followed the Zimmerman/Martin killing at all, you probably recognized that this is not what the dispatcher said. The correct transcript is:

Dispatcher: Okay, we don’t need you to do that.

Nowadays, we don’t tell people what to do and what not to do. We don’t tell them what they should or should not do or what they ought or ought not to do. Instead, we talk about needs—our needs and their needs. “Clean up your room” has become “I need you to clean up your room.”

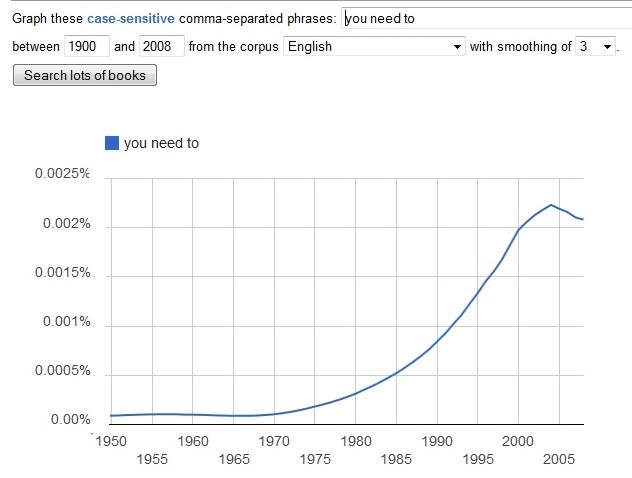

The age of “there are no shoulds,” the age of needs, began in the 1970s and accelerated until very recently. Here are Google n-grams for “you need to” and “they need to.”

We don’t say, “The writers on Mad Menought to watch out for anachronistic language.” We say that they “need to” watch out for it. It was Benjamin Schmidt’s Atlantic post about Mad Men that alerted me to this ought/need change. Schmidt created a chart showing the relative use of “ought to” and “need to.”

All of the films and television shows in the chart are set in the 1960s. But the scripts that were actually written in the ’60s are more likely to use “ought;” the ’60s scripts written in the 21st century use “need.”

Real imperatives (“Stop that right now”) claim moral authority. So do ought and should. But need is not about general principles of right and wrong. In the language of need, the speaker claims no moral authority over the person being spoken to. It’s up to the listener to weigh his own needs against those of the speaker and then make his own decision.

No wonder Zimmerman felt free to ignore the implications of the dispatcher’s statement. It was not a command (“Don’t do that”), it did not assert authority or the rightness of an action (“You should not do that”). It did not even state what the police department needed or wanted. It merely said that Zimmerman’s pursuit of Martin was not necessary. Not wrong, not ill-advised, just unnecessary.

If the dispatcher had spoken in the language of the 1960s and told Zimmerman that he should not pursue Martin, would Trayvon Martin be alive? We cannot possibly know. But it’s reasonable to think it would have increased that probability.

Philip Cohen, for what it’s worth, tells me that a TV commentator said that dispatchers have a protocol of not giving direct orders. If such an instruction led to a bad outcome, the department might be held accountable. So police departments’ efforts to avoid lawsuits may also have contributed to Martin’s death or, at least, the not-guilty verdict for Zimmerman.

This post originally appeared onSociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site.