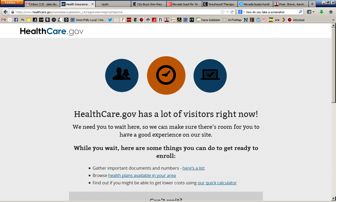

When I initially tried to sign up for health care in October, I was met with the inevitable:

As an unmarried freelance writer over the age of 26, the notion of public health care is deeply appealing to me. I would have greatly preferred a single-payer health care bill to this distinctly American brand of universal health care—an inefficient market-oriented plan that excludes millions of poor people of color—but it’s here, so I’m giving it a try. I never thought there was any likelihood that the law, if there were to be one, would be anything more than what it is: a safety net expansion bought with giveaways to most of the big players in the medical industrial complex. As anyone who honestly looks at America’s political institutions will tell you, our system is best at preserving the status quo. In a country without strong unions or other social movements, our politicians either work with industry or don’t work at all. And as Ezra Klein pointed out to my 23-year-old self, a single-payer system was too radical for the vast majority of Americans who already had health care in 2009: “You can’t underplay the fact that people do not want you to take away what they have. … There is a reason single payer has failed every time it comes up on a state ballot.” (This is no longer true: In 2011, the state of Vermont passed a law that would implement a state-level single-payer system by 2017.)

In the years since the Affordable Care Act was passed, I got health care from my parents’ plan until I turned 26, then received it from an employer, and after a round of downsizing, via COBRA. (This 1980s response to the mass plant closings of that decade allows workers to stay on their employers’ group plan for the low, low price [PDF] of the entire premium, plus administrative fees.) As a reasonably spry young man—with a chronic pain condition—I could have shopped on the individual market for a reasonable rate, but I liked the health care plan I had and was hired by a new employer who was willing to subsidize it. As I calculated it, my COBRA “benefits” would come to an end just as the Affordable Care Act got rolling in early 2014.

Living in Pennsylvania, one of the many states that refused to institute its own exchange, meaning I’d have to use the federal website, I read the doom-laden headlines about HealthCare.gov’s rollout with alarm.

AS NOVEMBER CAME TO an end, and the White House assured us the website was finally functional, it was time to take another shot at it. The complaints of those whose premiums went up didn’t seem too worrisome: That is what happens when insurance companies suddenly have to cover everyone and not just cherry pick young and healthy customers while preying on, or forsaking, the old and sick. Over 100,000 had signed up in November, so I decided it was time to join the December rush. (To get coverage that starts on January 1, you had to sign up by December 23, although open enrollment for 2014 ends on March 31.) After the first two days of the month, a further 29,000 had signed on the federal exchange, a higher count than all of October.

But while the White House waxed enthusiastic about the improved consumer experience, as The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf noted, they didn’t talk much about the part of the process where the website connects my order with whichever insurance company I chose. Friedersdorf cites this New York Timespiece on the efforts to fix the damn thing:

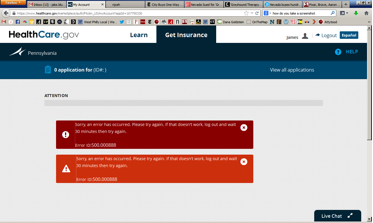

… it remains unclear whether the enrollment data being transmitted to insurers is completely accurate. In a worst-case scenario, insurance executives fear that some people may not actually get enrolled in the plans they think they have chosen, or that some people may receive wrong information about the subsidies for which they are eligible.

Further reporting from the Washington Post didn’t make me feel much better. In the autumn, 25 percent of enrollment files contained errors; now that number has fallen to a still-high 10 percent.

There are situations where HealthCare.gov doesn’t generate any transmission at all, times when it generates duplicate transmissions and situations where the transmission occurs but contains inaccurate information.

Worse, there’s no way to tell if you are one of those unlucky tens (if not hundreds) of thousands. You don’t want to learn of their error on January 6 while picking glass out of your face in an emergency room.

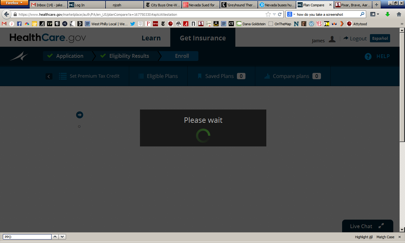

I STARTED MY EXPERIMENT on a Monday night, as I’d been advised that even though the website could now handle 50,000 users simultaneously, it was best to avoid the busiest times of day. Stick to the early mornings or late nights.

I found HealthCare.gov perfectly easy to use and, to my delight, literally every offering on the precious metal spectrum—from Bronze plans to Platinum—was substantially cheaper than what I’d been paying for my hideously expensive COBRA coverage. Even with a Platinum plan, the best on the exchange, I’d be paying almost $50 less per month in premiums, with co-pays, deductibles, and prescription plans that are comparable (although no dental), if not cheaper, than what I currently pay.

There is a problem with navigating HealthCare.gov at night, though. You eventually have to interact with the insurance companies, and their websites don’t make it easy to see if your doctor(s) take the HMO plans that are, of course, the cheapest options on the site. Since I’d be saving roughly $1,200 a year if my doctor did take the HMO in question, it was best to postpone completion until morning.

I awoke to find a world blanketed in snow. After calling my doctor—HMO plan: accepted—I tried to log on and was met with the chirpily dreadful: “HealthCare.gov has a lot of visitors right now!” It appeared as though all of my snowed-in neighbors had the same idea as me and the poor pajama boy. It was like October—except with all-new our-website-still-doesn’t work pages.

After staring in dazed horror at this medley of annoying backdrops, I resolved to wait a few hours, and then, when my neighbors had sunk into the inevitable hot chocolate-induced fugue state, continue my applications. In the meantime, I checked in with my dentists, who didn’t take the dental plans on offer. However, they offer teeth cleanings at such a reasonable rate that I’m just going to pay out of pocket which, at twice a year, is substantially cheaper than the amassed premiums.

Night finally fell, and I chose my plan—a Blue Cross Blue Shield HMO, available under the Gold plans—with a premium of $259.37 a month, no deductible, an out-of-pocket maximum of $6,350, and primary care co-pays of $15, specialist co-pays of $40, and $10 for generic drugs. Like many HMOs, my new plan will have two in-network tiers, the second with substantially higher co-pays, leaving me with the responsibility of wasting my life trying to figure out which is which.

But as soon as the confirmation flashed across my screen, I realized I hadn’t yet paid. Baffled, and a bit creeped out (wait, did they know my credit card information?), I called the HealthCare.gov mainline—a 20-minute wait—only to have the attendant tell me he couldn’t possibly help and that only the insurance company could do so (and no, they hadn’t craftily jacked my financial data without my consent). In the morning, I called the insurance company, and I was informed that I should be receiving a confirmation letter sometime in the next two weeks. (As of December 19, this has proved inaccurate.) Not to worry though, I’d have until the 31st of December to pay. They did not offer to review my information to confirm if I had, indeed, been signed up.

This wasn’t particularly reassuring. White House press secretary Jay Carney recently divested the White House of the responsibility for any screw-ups: “If consumers are not sure if they are enrolled, they should call our customer call center or the insurer of their choice so they can be sure they’re covered by Jan. 1.” I’d called both. Neither helped much.

Carney’s comment crystallizes one of the worst faults of Obamacare. It still sticks the individual with too much responsibility, which will be an especially difficult barrier for working parents—already chronically strapped for time. What about those who aren’t particularly skilled at navigating websites or who don’t have home Internet access? Medicare for all would, among other advantages, involve substantially less paperwork for the individual Americans not being paid to figure this stuff out. Signing up for health care on the national exchanges wasn’t an arduous process for me, but it was an annoying and distasteful way to use my free time. I ended up spending several hours over the course of multiple days on HealthCare.gov, and I’m still not sure that I will be covered next year. I hope I’ll receive that letter—why not an email sent as I signed up?—soon. If not, well, I’ll just have to cultivate agoraphobia until I figure out if it’s safe to leave my house this January. Or maybe I’ll get snowed in with some nice European in the interim, and this time next year I’ll be enjoying actual universal health care on the French Riviera.