You don’t walk through Centre Memorial de Gisimba alone. Step inside the gate of this orphanage in the Rwandan capital of Kigali, and soon you’ll have a child holding firm to each hand. You’ll acquire more instant friends with each step. Little arms wrap around yours. Little hands clutch at your clothes. Toddlers reach their arms skyward in the international signal for Pick me up! Smiling children sing, dance and thrust toys, vying for a precious resource: attention. Though their caregivers seem committed and affectionate, the children crave one-on-one time. Like most Rwandan orphanages, this place is full. The matrons and patrons must spread themselves around to accommodate the needs of so many.

Kevin Kalisa, 26, says visitors never got an exuberant greeting when he was at Gisimba. “Everyone was so sad,” he remembers. As a child, Kalisa says, he just wanted to be left alone, so he could focus on a single ambition: Killing the people who had murdered his family. Perhaps revenge that specific was out of his reach, but there was plenty of opportunity to kill génocidaires, the men who terrorized Rwanda during the mass murders of 1994 and the preceding years of sporadic violence. All he needed was an opportunity to go to Congo, where so many of the killers had fled and where the battles between Tutsi and Hutu that scarred his childhood have never stopped raging. “My plan was for bad things only,” he says.

He even ran away to become a kadago, or, literally translated, a “little one.” Kadago are child soldiers, often servants to their adult counterparts. Kalisa was especially attracted by the chance to learn how to use a gun. He was 12 years old. For Kalisa, however, military life was brief. A relative in the army found the boy, beat him and commanded him to leave kadago training. At the time, it was a disappointment.

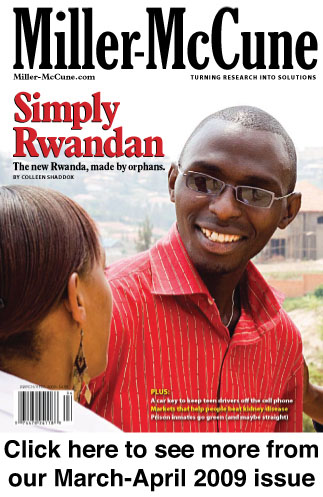

But Rwanda has since demobilized its child soldiers, and today Kalisa is an outgoing man with a broad grin and a firm handshake. He’s also a law student, thanks to funding from the nonprofit Orphans of Rwanda Inc. While education aid in the developing world tends to focus on primary education, Orphans of Rwanda devotes itself to students in college. Two Americans with nonprofit backgrounds, Dai Ellis and Oliver Rothschild, co-founded the organization in 2004 to focus on developing a generation of Rwandan leaders through college scholarships and links to other opportunities. They envisioned young Rwandans assuming key positions in business, government and nonprofits. Kalisa was in the first cohort of students. There are now more than 160.

Like many Rwandans of his generation, Kalisa was orphaned by genocide. He lost most of his family in a wave of persecution against ethnic Tutsi in 1992. It was a precursor to a larger genocide in 1994 that staggers the imagination. In 100 days, between 800,000 and 1 million Rwandans were murdered by their neighbors, ordinary people mobilized to unspeakable violence through a carefully orchestrated campaign of government-led hate. The victims were minority Tutsi and “Hutu traitors” who tried to help them. Institutions crumbled in a country already gripped by desperate poverty and an AIDS epidemic. Schools closed. Hospitals had no doctors, no medicines. It seemed that the country — and children like Kevin Kalisa — had no future. But that was in another time and what seems like another country, when people were either Tutsi or Hutu, before the time when you could be just Rwandan.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xON22c7pZ6chttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eDYMFyKV3pUOptions to Vengeance

The pre-colonial history of Rwanda is unrecorded. This much is certain: Tutsi owned cattle and comprised the aristocracy. Hutu farmed. Some historians believe that Tutsi and Hutu were merely job descriptions. A Hutu who acquired enough cattle could become a Tutsi. English explorer John Speke maintained during the Victorian Age that the Tutsi were of Ethiopian origin and could trace their lineage to King David, while the Hutu were children of Noah’s son Ham, cursed by his father to be “a slave of slaves.” It was an ethnographic fairy tale based on no evidence whatsoever. But its influence has been far reaching.

When the Belgians actively colonized the country after World War I, they naturally aligned themselves with the Tutsi, who were already in charge and boasted a romantic lineage in the Speke account. The Belgians encouraged a more polarized division between the groups and even began printing identity cards that labeled the holder as Hutu or Tutsi. After World War II, however, the Belgians switched their allegiance to the Hutu. A new generation of clergy, many from humble stock, was evangelizing Africa and quick to point out the inequality of Tutsi rule. By the time the country gained independence in 1962, Hutu dominated the government and began a quota system that froze Tutsi out of jobs and educational opportunities.

Like many Tutsi, Kalisa’s family fled to Uganda. He was born there in 1982. Most of these refugees continued to consider themselves Rwandan and dreamed of returning. Kalisa’s family came home to Rwanda in 1987 when civil war broke out in Uganda. They settled in Nyamata, an area that then was predominantly Tutsi. He has fond memories of helping his stepmother tend the family cattle on the rolling green hillsides that dot this country. Rwanda is called “Land of a Thousand Hills,” which seems an understatement. Cattle constitute more than material wealth. They are an extremely powerful symbol in Rwanda, important in marriage contracts and other social matters. Kalisa’s family had 150 head of cattle. Surrounded by this extended family, he grew up dreaming of being a doctor, inspired by his father’s career in nursing. He was a happy child with a bright future before him.

But a whirl of political events ended that happy, pastoral life. Many Tutsi refugees were still fighting for the right to return to Rwanda. The Rwandan Patriotic Army, formed by exiles in Uganda, began crossing into Rwanda in 1990. A three-year-long civil war began, and ethnic tensions reached new heights. In 1992, Kalisa saw 28 members of his family murdered and their cattle stolen by machete-wielding killers. With a surviving twin sister and younger brother, he shuffled between orphanages in search of safety before arriving at Gisimba. The younger brother was adopted by a French couple and taken out of the country. “They never give any news,” says Kalisa, who knows nothing about the whereabouts or well-being of his brother. “This is very common,” he adds. For the first time in the telling of his story, he looks visibly distressed.

In 1993, the civil war ended when the Hutu-led government agreed to concessions. But the official end of the war did not bring peace. A plane carrying President Juvénal Habyarimana was shot down over Kigali on April 6, 1994. Rwanda’s government barred United Nations investigators from the site. Who assassinated the president is a source of ongoing controversy. Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines, a broadcaster of hate programming, declared that the assassins were Tutsi “cockroaches.” For months leading up to this day, groups of young men had been organized in a militia, the Interahamwe, and supplied with machetes by people linked to the Habyarimana government. After the assassination, they were ordered to “do their work,” to kill Tutsi and moderate Hutu. The radio even broadcast the location of Tutsi hiding places. In the 100 days that followed, the Interahamwe went on a ghastly spree of murder, rape and torture. The U.N. forbade the small force it had in Rwanda to do anything more than observe, despite pleas from the commander on the ground to send more troops and authorize them to defend Rwandans from the death squads. The genocide ended when the Rwandan Patriotic Army marched into the country and seized control. Many members of the Interahamwe and the old government’s military fled Rwanda, where some of their comrades fell victim to revenge killings, to neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo. Many refugee camps were controlled by Interahamwe who used them as a base to launch raids into Rwanda. By then, Rwanda was controlled by the Rwandan Patriotic Front, a government established by the rebel army. For years afterward, the Rwandan army would launch raids into Congo to seek out the Interahamwe raiders.

Kevin Kalisa very much wanted to go along. At 22 years old, he had only a high school diploma. He lived in a society where family connections can be useful in the competition for scarce jobs. Kalisa had very little in the way of family. He had nowhere to go when he left the orphanage. He applied for and was accepted into military training. “I wanted to avenge,” he recalls. And it was not as if he had many alternatives.

He credits Dai Ellis with talking him out of his plans. “He was so close to me,” Kalisa says. “He was the first person to whom I told my problems.”

Ellis remembers it differently: “We were talking to them about what their future could look like. I don’t think I actively tried to talk him out of the army. But I think we tried to talk him into the idea that if you can qualify for university and we can make a commitment to you — we can support you through all four years — that might open up quite a few doors for you. Most kids don’t really need to be sold on that.”

Their Own Wings

Because of the genocide, Rwanda doesn’t just have an orphan problem; it has a huge cohort of orphans who are reaching their 20s — that is, “aging out” of the orphanages — without any means of supporting themselves. Meanwhile, the AIDS epidemic has created a new group of younger orphans. Because education was so disrupted by the genocide, it is common for people in their 20s to still be attending the equivalent of middle or high school. Until recently, even in good times, there was no standard age to begin school. Kalisa, for example, did not start school until he was 8 because of his responsibilities with his family’s cattle.

Seeing the gap in services for young adults in the wake of the genocide, Rothschild and Ellis decided in 2004 to form a nonprofit that would focus on leadership development by providing college scholarships to orphans. They had been working for the Access Project, a branch of Columbia University’s Earth Institute that focuses on building management capacity in public health systems in impoverished countries. Their working life seemed to involve more spreadsheets and high-level meetings than contact with needy Rwandans they were trying to help. Both speak passionately about the importance of building good business practices into international development. But both were hungry to act on a more personal level.

They started by raising funds to send 11 orphans to college. Kalisa was one of them. There was no selection process. They were simply young people ready to leave the orphanages that these two Americans had already been assisting. It was an enormous undertaking. Rothschild, then 24, was on his way to medical school; Ellis, 28, had been accepted into law school. Asked if he had any hesitation about starting up a formal organization, Ellis laughs and says, “I should have.” For more than two years, there was no American-based staff for Orphans of Rwanda and only one staffer in Rwanda. In addition to attending law school, Ellis had taken a job with the William J. Clinton Foundation. With the demands of running Orphans of Rwanda, “There was a point where law school was third on my list,” he recalls.

Rothschild and Ellis were studying at Yale but remained committed to Rwanda, taking classes in Kinyarwanda, the Bantu language that is spoken only in Rwanda, a country the size of Vermont. On their trips to Rwanda, they continued to learn just how much support students would need to succeed.

Today, Orphans of Rwanda has five Rwanda-based staffers, whose efforts are augmented by those of volunteers and consultants. They provide a broad range of services to the 167 students, including housing, a monthly living stipend and health care. A few of the students live independently in apartments paid for by the nonprofit. But most live in single-gender group homes near whichever university they attend.

The nonprofit also invests in academic support; for example, it tests students for computer skills, provides computer classes for those who need them and has a computer lab in the organization’s Kigali office for students to use. The organization recently put a computer in each of the group homes.

Students enter the program in October, when most Rwandan schools are in recess. Some apply soon after completing secondary school; others have been working for several years when they learn about the opportunity. Most are in their early 20s. They come to the organization’s Kigali headquarters for months of preparation. They will continue to get supplemental academic assistance when school starts in January and throughout their four years at university. Often, language is the area where students are in most dire need of help.

At home, most Rwandans speak Kinyarwanda, but secondary and higher education are conducted in English and French, usually depending upon the language preference of the instructor. Recently, the government announced that all instruction would be conducted in English by 2010, though French is a more common second language in this former Belgian colony. Those who have been refugees in Uganda or Congo usually have some grounding in English, but most are not fluent. So all students get supplementary language instruction, including formal classes in English as well as discussions of English-language videotapes donated by the U.S. Embassy. (Imagine 15 college students discussing Annie Get Your Gun.)

Orphans of Rwanda constantly monitors student performance to see what other types of support could boost success. Many students see their textbooks clearly for the first time in their lives when the organization buys them eyeglasses. Others get long-needed trauma counseling. But the most striking benefit that students mention — in conversation after conversation — is the chance to regain something precious: a family.

“Many Brothers and Sisters”

A half-day’s drive from Kigali, National University of Rwanda nestles at the edge of old-growth forest. National University is in Butare, where the kings of Rwanda made their capital. It is easy to understand the royal choice. Even in a country with a nearly ideal climate, Butare is exceptional for its almost constant cool breezes. Many streets are sheltered by a canopy of trees. Sometimes monkeys venture to the roadway leading up to the university and stare down at arriving students from perches high in eucalyptus trees.

This is a college town, albeit with more dirt roads than most. Some buildings are European-style; others are the signature local mud brick construction, often painted in white, yellow or robin’s-egg blue. Still more are a mixture of the two. There are restaurants, cybercafés and — an oddity for Rwanda — nightlife. Ubiquitous signs for Fanta soft drinks and Primus beer invite passers-by in.

National is the most selective university in the country. It was ranked 30th among Africa’s 100 top universities in a recent independent ranking and has a strong research base, which is by no means standard in Rwandan higher education. Every year, more Orphans of Rwanda students are being admitted here; in the fall, there were 35. Sylvère Mwizerwa is one; he’s also a big man on campus, with high-fives and jokes for half the people he passes. The first-year student is chief of promotion, elected by his fellow students to serve as a liaison to the school administration. “I’m building my CV,” he explains.

Mwizerwa is focused on the future because the past is nothing but “regret and problems.” He plans to be an entrepreneur. “Our background is very bad. So there is only one way to change the history of my country. (Through) the opportunity of ORI, I can choose my change, and I have to exploit it very good because this is my chance,” he says.

He shares that chance with nine other young men and a newly acquired kitten in a small house just off campus. It is one of the group homes that Orphans of Rwanda provides for students. At lunchtime, the men gather around the table to eat rice, beans and avocado. They pool their ORI stipends and share expenses. They also tease each other mercilessly. Mwizerwa, a sub on the university basketball team, explains that his housemate Emmanuel Maboneza can’t play because “he’s very old!”

There is much more going on here than banter between roommates.

“Instead of crying, we are laughing now,” says economics student Venant Msamzimfura. “We have brothers and sisters. We are in the whole family.” He refers to Orphans of Rwanda as a “father,” as do many of the students in the program. Though he is grateful for the college scholarship, he says the organization’s greatest gift to him was the chance to live with these housemates who call themselves brothers. “We have ORI to teach us how to live in society without living alone,” he says.

It is impossible to overstate the importance of family in Rwanda. “How many children do you have?” is a common icebreaker. If the answer is fewer than four, incredulity follows; Rwanda has always been a country of large families. So consider Jean Baptist Niawangiwabo, 27, who lost his father at 4 and his mother at 7. He spent his childhood homeless or shuffling between orphanages, with only two sisters to call family. Then, he lost one of those sisters in the genocide. “I see that God was looking at me,” Niawangiwabo says. “I have many brothers and sisters, as you can see.”

Orphans of Rwanda sponsors 10 women students who attend the Kigali Institute of Science and Technology, the country’s leading technology university. All of them live together in a stone house with exotic tiling that would not look out of place in Morocco. The house is in Kigali’s Muslim quarter, the city’s Bohemian neighborhood. The streets here are narrow and so full of pedestrians that cars often inch down the roads, which are hard packed with the red dust that is everywhere in Rwanda. Women in brightly colored saris or in batiks of the traditional Rwandan style stop and chat outside the Chinese market. Men and women in Western-style garb weave though the crowds while talking on their cell phones. Every café seems to spill onto the sidewalk, with overhead Christmas lights illuminating plates of goat brochettes.

The KIST students call each other sisters. They share clothes and casually play with each other’s hair as birth sisters might. They also make a righteous case for an expanded role for women in Rwanda. They are all studying some branch or another of information technology. This is out of step with the traditional role of women in Rwanda, which one of them describes as, “Look after the cows.” But it is very much in step with a widely held vision of the country’s future.

Julliet Busingye and her housemates plan to be among Rwanda’s vanguard of knowledge workers — or, more accurately, leading them. Male students outnumber females in her computer courses at the technology institute, a situation she says is common in higher education. When families have limited resources to educate their children, she says, “The boy goes on. The girl gets married.” In 2004, the most recent year for which government statistics are available, 60 percent of students at university in Rwanda were men. In the incoming cohort of 47 at Orphans of Rwanda, 55 percent of the students are women.

Busingye and many of her housemates say that they chose technology careers in part to prove that a woman can excel in a male-dominated field. Rwandans typically speak softly in conversation. (Westerners accustomed to louder voices often have to lean in to catch every word.) But when they speak of gender equity, these young women do it loud and clear.

Busingye also serves as head of student government at Orphans of Rwanda, which is one of the reasons she was selected to go on a monthlong fundraising tour in the United States before the January start of the Rwandan school year.

New York, New York

During the first leg of the trip, Busingye is staying in an ORI board member’s apartment in New York’s East Village. In a Brooklyn Theatre Arts High School T-shirt, she curls up on the sofa and describes her visit to the Statue of Liberty and her first encounter with pizza. Her dearest wish for the trip is to check out graduate programs. “It’s been my dream that I want to do women’s studies as my master’s,” she says, noting that there are no such programs in Rwanda.

Actually, though, the highlight of the trip has been a ride over Long Island Sound in a small plane. It is special because it meant so much to her “brother,” Nicholas, another Orphans of Rwanda student on the tour. (They are not biological siblings; Orphans of Rwanda students frequently refer to each other as brother or sister.) Nicholas Rutikanga looks up from his laptop, smiling under a watch cap embroidered with “USA”; he plans to check out aviation schools in the U.S. He has dreamed of being a pilot since he was a boy, tagging along on trips with his mother, who was a flight attendant, until the genocide raged through his country.

When he was 6, Rutikanga’s mother learned she was on an Interahamwe hit list and went into hiding with him and his brother, Rutihinda Joel. An odyssey ensued, nights spent in the backs of trucks, abandoned homes and forests. Rutikanga narrowly escaped the militia once, suffering a serious machete wound to his leg. The family fled to Burundi, later returning to Rwanda and finding most of their extended family dead. Rutikanga’s mother fell seriously ill and couldn’t take care of her sons; she didn’t have any family to help her. So she entrusted her children to the Gisimba orphanage before she passed away. Rutikanga gave up on being a pilot.

Then, two years ago, he was accepted into Orphans of Rwanda at age 21. “It was like a second chance,” he says.

When Rutikanga applied, he was the shyest kid Ellis says he had ever met. But on a night last October, Rutikanga donned a black suit and silver striped necktie. He strode confidently to a podium in the Sunset Terrace at Chelsea Piers and addressed a crowd of Manhattanites — supporters and potential supporters of Orphans of Rwanda. He talked about the services the organization offers but mentioned his hardships only in a veiled way as “things that happen in your life that you never forget.” The focus of his talk was his future — as an engineer and a pilot — and Rwanda’s. He built to a crescendo that any orator would envy, waving his fist in the air and declaring, “I’m ready to change the future!”

Days later, Ellis still beamed when he talked about the performance, in no small part because when Rutikanga began university just two years ago, his English was “almost nonexistent.”

“I Had to Rebuild”

Ellis says there’s a lot of groupthink in Rwanda, and it’s one reason so many Orphans of Rwanda students say they have the same career goals, which fall broadly into three categories: information technology, human services and finance. He believes many of the students are just latching on to careers being touted by the government or talked about by friends. So Orphans of Rwanda is trying to expose students to more choices through internships and career events. The organization also tries to encourage students to develop the habit of asking questions, even of themselves: “Is this what I really want? Why?”

But Kassim Mbarushimana is an exception who’s thinking decidedly out of the box. He wants to start an orphanage, of course; helping orphans is a goal that Orphans of Rwanda students almost universally voice. But he also wants to be a lawyer. “I have a lot of experience about human rights,” he explains. He would also consider a career as a radio announcer and has definite ambitions to be an actor. “I want to know a lot of things, because you don’t know what will help you.”

In fact, Mbarushimana is already an actor. He and his friends made a film, Take a Decision, in which he plays the lead, “Eric,” a young man whose hesitant parents finally talk with their teenage children about HIV/AIDS transmission. The kids get tested and urge their friends to do the same. Two of Eric’s friends are HIV-positive, and he tells them that with anti-retroviral therapy they can have many healthy years ahead of them.

The film is in English, which made it a challenge; Mbarushimana has been speaking the language only since 2007, when he was accepted into Orphans of Rwanda. But, he explains, an English-language film has a potential market that is larger than Rwanda — the East African Community, a regional organization that aims to promote trade and economic development. It’s a point he and his colleagues have been making while seeking financial backers.

Actually, though, Mbarushimana’s ambitions are larger; he’s thinking Hollywood. He wants to write a screenplay based on his life. He was already orphaned when the genocide began and was living with an uncle in Kigali. The first time soldiers shot their way through the front door, his grandmother convinced them that the family was not Tutsi. The drunken leader of the pack believed her. A Hutu neighbor hid the family for a month until it became unsafe to stay. They heard that refugees were safer in Gitarama, about 20 miles to the west, but they had no way to get there. Eventually, a man offered to drive them if an aunt would “be his wife.” She contracted AIDS from the relationship, giving her life to save the family, Mbarushimana says. In Gitarama, they lived in the streets and dodged the death squads.

In ensuing months, Mbarushimana was beaten over the head with a club embedded with glass shards. His aunt was gang raped. Eventually, Mbarushimana and the aunt were rescued by Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers, but the uncle who was his guardian had been murdered. Mbarushimana lived with his grandmother, but she had no means of support. Through the help of survivor groups, he managed to get through secondary school. But the joy was gone from his life. No more soccer, no more music, few friends.

His screenplay idea is such a decidedly sunny adaptation of this almost unimaginably horrifying reality that it is hard even to see its roots in the real story. The screenplay is about a boy and a girl from different sides of the tracks. Mbarushimana identifies with the girl, who is poor and uneducated. Both families disapprove of the match. But she manages to get an education, becomes very rich and teaches all concerned important lessons about equality and courage. In truth, there are just two similarities between the proposed film and reality: a belief in the power of education and the hope for a happy ending.

Today, Mbarushimana is full of ideas and ambitions. He has a wide network of friends, many of them Orphans of Rwanda students. And, of course, there are the people he meets at the local salsa club. He likes music again. In fact, he’s such a good dancer that he’s become an instructor. The obvious and maybe unanswerable question is how. How do Mbarushimana and his peers manage to keep putting one foot in front of the other, let alone dance?

“I couldn’t stay in a negative way. I had to gain my life. I had to rebuild my life,” Mbarushimana says. “I can’t say that I have forgotten all, but I am trying.”

Many Orphans of Rwanda students say that they are quite happy in their daily lives. But there are times when the sadness of the past comes back. One talks about dreading holidays. Another dislikes the rain because the genocide happened during the rainy season. Kevin Kalisa is rarely without a smile as he goes about his business in Kigali. “I am only sad in Nyamata. Just when I pass there,” he says.

“Agonie!”

There is a new road to Nyamata, which has cut the travel time coming out of Kigali from three hours to less than one. This is one of many attempts to modernize Rwanda’s infrastructure. The improvement in the road is most apparent where the new highway crosses the Nyabarongo River. Beside the modern span is an old log bridge that was once the only way across. The new road makes it much quicker to drive to one of the country’s major genocide memorials. There is talk of making the river itself a memorial because during the genocide it was choked with bodies.

Since Rwanda became independent in 1962, when periodic violence broke out, Tutsis would often seek shelter in churches and schools. In Nyamata Church, the strategy failed. Today, every pew is piled with the clothing of the thousands who sought sanctuary there. Their fate is told in the rusty bloodstains on the altar cloth and walls. There are bullet holes in the ceiling, and birds fly in and out through the broken stained glass. In a crypt below, a coffin draped in purple and white rests under glass along with bones and artifacts, including the identity card that one of the fallen carried.

In an outside crypt, more coffins rest, one atop the other. There are thousands of skulls and bones stacked neatly. Some show breaks from the machetes. It seems ancient, archaeological, except that occasionally a family has left a fresh bouquet or a sign, memorializing a loved one. “Tierry Nyrigira Armand. Nè Le 23 March 1993. Morte Le 26 Avril 1994.”

Andre Lamana oversees the Nyamata area’s four genocide memorials. “It’s not a good job,” he says through an interpreter. During the violence that took Kevin Kalisa’s family, Lamana was in Burundi, about 30 kilometers away. Two of his children had stayed behind in Nyamata; they were killed in the church. Lamana describes what it is like to work at the scene of his children’s murder. He clutches all over his torso and repeats a French word that needs no translation: “Agonie!” Lamana says that he comes to work every day “to tell everybody.” He insists that ethnic hatred in Rwanda was a Belgian import, a device to divide and conquer.

There are no more identity cards separating Rwandans by ethnicity. It is illegal to promulgate “genocide ideology.” The most popular bumper sticker in the country proclaims, “Proudly Rwandan.” No one publicly identifies him- or herself as Hutu or Tutsi, though clashes between those groups continue to flare just over the border in Congo. The very idea of being simply Rwandan is a hallmark of President Paul Kagame‘s influence on the country. “Today, everything has changed,” Kalisa says. “The government is no longer about division. The government used to divide.” Ethnic division has been erased not only from identity cards but also from the hearts and minds of Rwandans, Kalisa says; no one knows whether his or her neighbors are Hutu or Tutsi. Pressed on the point, he shrugs. “Well, maybe you know. But you never care about it. It’s not big,” he says.

Kagame, a Tutsi who led the Rwandan Patriotic Army that ended the genocide, was elected president in 2003 and seems to enjoy popularity. Admittedly, his election was accompanied by widespread allegations of voting fraud, and it is hard to gauge public sentiment in a country with little in the way of independent media. Also, Kagame’s rule has been seen as less than democratic, a form of enlightened authoritarianism. But people on and off the record praise the president for his “vision,” and aid workers talk with apprehension about a time in the future known merely as “after Kagame.” The nation’s recovery is so linked to his work that they wonder what will happen someday when Kagame is no longer in power. Where will the next visionary come from?

Kagame’s government had laid out a plan to achieve widespread prosperity by the year 2020 through the construction of a knowledge-based economy. Orphans of Rwanda is playing a part in realizing the plan, “Vision 2020,” says James Kimonyo, Rwanda’s ambassador to the United States. “It is only through education that the developing world and Rwanda in particular … will be able to improve the lives of the people,” Kimonyo says.

Rwanda is tiny and landlocked; it has few natural resources, save the mountain gorillas that draw some tourists. Most of the nation’s rapidly growing population of about 10 million relies on agriculture for support. But there is simply not enough land to provide a living wage for every Rwandan. That’s why the country is turning to technology and banking. Rwanda alternately refers to itself as the Singapore or Switzerland of Africa, even though almost no businesses accept credit cards and Internet connectivity is never a sure thing. But on every street corner, young men sell cellular phone cards. And while many of the streets in Kigali are still unpaved, most are being dug up, because the entire city is being wired with fiber-optic cable.

The government gives out at most 3,000 university scholarships annually, Kimonyo says, but a larger corps of university-educated people is needed to blaze the trail to prosperity. The ambassador is a strong supporter of Orphans of Rwanda, stumping for the organization at fundraisers in the U.S. and praising the group for helping turn the neediest young people in the country into a source of hope. “They have the potential to be good citizens,” he says.

The faith the average Rwandan has in the country’s future is palpable. Many Orphans of Rwanda students have “2020” in their e-mail addresses. It is difficult for these young people to imagine that outsiders would see Rwanda as anything but a land of promise.

Orphans of Rwanda student Gerardine Benimana sits by the buffet in a Butare restaurant, near National University, where she is in her first year. She is preparing to be a psychologist and hopes to work with trauma survivors. She’s looking out the balcony into a typical balmy Rwandan day. What, she would like to know, do Americans think of Rwanda? Informed that most Americans know little about Rwanda save its history of genocide, Benimana’s eyes go wide, and she sits up very straight. “You have to tell them,” she insists. “You tell them that there are university students here working very hard, that many people are working very hard. Tell them that good things are happening in Rwanda.”

Her friend and classmate Aline Umutoni pushes some chips around her plate and listens intently. After a very long pause, she asks a question: “Were you afraid to come to Rwanda?”

No, I tell her; I’m never afraid when I’m working on a story. But my husband was a bit afraid.

“Then next time you come back, you bring him with you,” she says. “You will bring your husband and your son, and they will see that Rwanda has good security.”

The New Citizens

In the wake of genocide, Rwanda has done some large things right. The country instituted universal primary education, Orphans of Rwanda co-founder Oliver Rothschild notes, and cut its malaria prevalence rate by more than 60 percent. Advances like these make it feasible to invest in something like higher education, he says. Krishna K. Govender came to Rwanda from his native South Africa to be rector of the School of Finance and Banking in Kigali. He terms his job “a calling.”

“Clearly, there is a lost generation that needs to be empowered, that needs to be reorientated, that needs to be skilled. They make up the future … managers, leaders, entrepreneurs, mothers, fathers — the new citizens,” Govender says.

Educating those new citizens using old ways will not work, Govender believes, so he is making sweeping changes to the school’s curriculum to give students more of a liberal arts grounding. Traditionally, higher education in Rwanda was oriented toward preparation for a specific profession. Govender says he was drawn to Rwanda in part by the Kagame government’s bold plans for progress. “He’s not stuck in the old way of thinking. He’s a reformer,” the rector says and then pauses and chuckles. “Sometimes I feel sorry for him.”

Govender knows all about being a reformer on a budget. The campus library has a total of three bookcases full of volumes, each about 10 feet wide and ceiling high. The main lecture hall has a chalkboard not visible to at least half the students in the room and a public address system reminiscent of a commuter train. Fewer than 70 faculty members serve 2,500 students, a shortage Govender blames on low pay. Master’s-prepared teachers earn about $400 monthly. Govender waves his hands about the courtyard, where students have dragged desks because there is no room to study in the library. “Despite all this, there’s still a success story,” he declares.

The School of Finance and Banking is one of the country’s best universities, Ellis says, and Orphans of Rwanda works with universities to improve the quality of higher education. Still, Ellis talks about a “pipe dream” — the organization starting its own university some day. His musing raises an open question: What will this young organization eventually become? “Are we really trying to be a GI Bill, or are we trying to be a Rhodes scholarship?” Ellis asks.

Orphans of Rwanda started out with no selection criteria. Today, only about 4 percent of the applicants make it through an extensive selection process that includes an interview where prospective students must answer in French or English. The organization is, Rothschild likes to say, “more selective than Harvard.” Newer students are the best and the brightest, high achievers who have overcome unthinkable obstacles. They are, the organization holds, destined to be the nation’s leaders.

But what about young adults who cannot meet Orphans of Rwanda standards? Ellis says the board may end up discussing a vocational track. A key to any decision will be gathering data about the current programs, with two goals in mind: to hook new graduates with alumni who might offer them employment and to measure the impact of people who have gone through the program. Ellis says his vision is to build a network of highly skilled people “feeling like they have a kind of collective mission to change the future of Rwanda.”

Ordinary Time

On a Saturday morning, women with buckets of sudsy water and stiff brooms are scouring the floors and wooden benches of Sainte Famille Church in Kigali. The parish priest, Father Wenceslas Munyeshyaka, was sentenced inabsentia to life in prison by Rwandan authorities for his role in the massacre that took place here. Survivors say that Munyeshyaka participated in rapes and murders. He fled to France shortly after the genocide. The United Nations’ International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda gave France jurisdiction over the priest. France and Rwanda have severed diplomatic relations, so extradition is highly unlikely.

Stephanie Nyombayire is frustrated with what she sees as foot dragging on the part of international authorities that have yet to hold the masterminds of the genocide accountable. “They have impunity,” she says. While a student at Swarthmore College, Nyombayire co-founded the Genocide Intervention Network. Originally formed to organize on behalf of genocide victims in Darfur, the group’s goal is to create “a permanent constituency against genocide.”

When she graduated from college in 2004, Nyombayire considered staying in the U.S. to continue building the Genocide Intervention Network. But she returned to Rwanda, where she’d spent much of her childhood and where she now works for Orphans of Rwanda. She says she is as passionate about helping Rwanda recover as she is about preventing genocide.

“Genocide is always planned, and it is planned by the educated,” she says. “But it is committed by the uneducated.” Today she is organizing a career workshop for new Orphans of Rwanda students in a hall behind Sainte Famille. Unlike other Rwandan churches where genocide occurred, there are no grim memorials here. The church continues to function as a place of worship, and the hymns of the congregation can be heard wafting up the hill to Kigali’s commercial district twice a day. Banners depicting Jesus, Mary and Joseph hang behind the altar, which is draped in green cloth. Decorations throughout the church are green because this is Ordinary Time, the longest season of the Roman Catholic liturgical calendar. Green is the color of Ordinary Time and meant to symbolize hope and growth.

The workshop will offer students tips on résumé building and writing, as well as some inspirational speeches by successful professionals. This morning, the nonprofit will break its own rule and offer a program in Kinyarwanda because it is the one common language for the incoming class.

It is clear — whether one speaks Kinyarwanda or not — that the talk given by Odette Nyiramilimo is the highlight of the morning. Her animated speech has students on the edges of their seats. Sometimes they laugh. Sometimes they hold their collective breath. Nyiramilimo does not tell her own harrowing genocide story, well known through the movie Hotel Rwanda. (Nyiramilimo, her husband and her children sheltered at the Mille Collines.) Instead, she holds them spellbound with the story of her careers in medicine and politics.

Nyiramilimo resolved to be a doctor when her mother suffered a miscarriage and the woman’s only option for medical care was a son-in-law. The mother found it humiliating to have an obstetric exam given by a male relative. Nyiramilimo promised her mother she would become a doctor one day and always care for her. At university, she was not placed in the medical track and could only be transferred with a letter from the minister of education. She camped out in the man’s office until he signed the letter; she believes he did so just to get rid of her. She became a gynecologist and after the genocide was a vocal advocate for rape survivors. This activism led to a Senate seat, and she is now Rwanda’s deputy to the East African Community.

A young man raises his hand and asks how she was able to discern the design that God had for her life.

“God helped me, maybe by giving me a brain or whatever,” Nyiramilimo replies. “But you design your own life.”

“I Was the One”

In the office of the Centre Memorial de Gisimba orphanage, Kevin Kalisa takes a pushpin from the bulletin board to remove a color snapshot that has nearly faded to sepia. “My first Communion,” he says. He’s about 14, looking very pious in a black blazer as he receives the sacrament. He smiles and puts it back. The office bulletin board is his family album. The little boys and girls following him around are “brothers and sisters.” At least three times a week, Kalisa returns to the orphanage to teach staff members English and computer skills. He reasons that if the matrons speak better English, the children will as well. That’s going to be important for their success. The director, Damas Gisimba, tries to pay Kalisa, but the young man won’t take the money. “I can never pay (the orphanage) back,” he explains.

He says that he is extraordinarily lucky to have gotten the chance at a university education and that his good fortune comes with an obligation. “I was the one,” he says. “And now I promise them to do the best thing and assist others who are in danger.”

Kalisa has friends and a cashier’s job at the city’s hottest restaurant, a place called Heaven, where expatriates and the growing ranks of prosperous Rwandans enjoy live music, martinis and a SoHo-style menu as they look down on the lights of Kigali. He works there while he finishes his memoir, a senior thesis. When done, he will be an attorney, a profession one can enter in Rwanda with a bachelor’s degree.

In fact, Kalisa has already been busy serving his local election commission, for which he educates his neighbors about their voting rights. “I was the only one with a legal background,” he explains.

He can’t stay at Gisimba long today. He’s got to be at Heaven to get organized for the lunch shift. After his day at the restaurant, there is that memoir to work on. Kalisa is also focused on finding a place to practice law. That, even more than these tutoring sessions for the matrons, is the best way he knows to help the children here. He laughs when asked about the demands of his schedule. “I’m always on my way somewhere,” he says.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.