Immigrant rights advocates warn that thousands of American residents of Vietnamese origin are at heightened risk of deportation, particularly as President Donald Trump prepares for a diplomatic visit to Vietnam, where he could pressure authorities—as he has done already in Southeast Asia and Africa—to take in more deportees.

A joint community alert issued Monday by a group of Southeast Asian-American community-rights organizations warned that Vietnamese immigrants with final removal orders are, more than before, “vulnerable to potential arrest, detention, and deportation.” Late last month, the notice said, Washington submitted 95 cases to Hanoi to be processed.

The alert, coupled with reports of rampant detentions of Vietnamese and other Southeast Asian-American communities is cause for worry for those who fear seeing their communities become yet another flashpoint in the administration’s anti–immigration policy.

“There is urgency now because [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] has ramped up their aggression against immigrant communities,” says Dieu Huynh, a community outreach coordinator for San Jose Vice Mayor Magdalena Carrasco and an organizer with the grassroots group VietUnity-PACT.

Historically, Hanoi refused to accept deportees from the United States, largely owing to Washington’s attempt during the Vietnam War to overthrow the country’s ruling administration. So those deportees’ cases remained in limbo until January of 2008, when Washington signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Hanoi allowing U.S. residents who arrived before July 12th, 1995—the date the two countries restored diplomatic relations—as well as those without criminal convictions to remain in the U.S. The agreement also laid the foundations for Hanoi to accept the deportations of those who did not fall in those categories.

But, by aiming to deport pre-1995 arrivals with removal notices, the Trump administration stands to upend the MoU. Less than a week after Trump’s presidential inauguration, he signed an executive order establishing that the Department of State would make “efforts and negotiations with foreign states” conditional on their acceptance of deportees. With Trump expected to travel briefly to Vietnam next week as part of a regional tour, it remains uncertain whether he will exert economic and other diplomatic pressures on Hanoi to accept deportees from the U.S. Meanwhile, a delegation of Vietnamese officials have arrived in the State of Georgia, which has a large Vietnamese community, to conduct interviews with people who arrived both before and after the 1995 date, the joint community alert said.

Trump’s Vietnam trip will be key, many advocates believe. “Donald Trump is set to visit Vietnam this coming week, and indications point to the Trump administration ramping up their efforts to separate Vietnamese families,” says VietUnity-PACT’s Huynh, who recalls that, last month, the administration imposed visa sanctions against four countries—Cambodia, Eritrea, Sierra Leone, and Guinea—for refusing to take deportees.

Others agree that Trump’s visit to Vietnam and how Hanoi reacts to this may represent a sea change in how the U.S. removes people of Vietnamese origin.

“Vietnam has historically only accepted individuals with deportation orders if they arrived in the U.S. after 1995, with the purpose of protecting individuals who came into the U.S. as refugees,” says Katrina Dizon Mariategue, the immigration policy manager at Southeast Asia Resource Action Center, the organization that sent Monday’s alert.

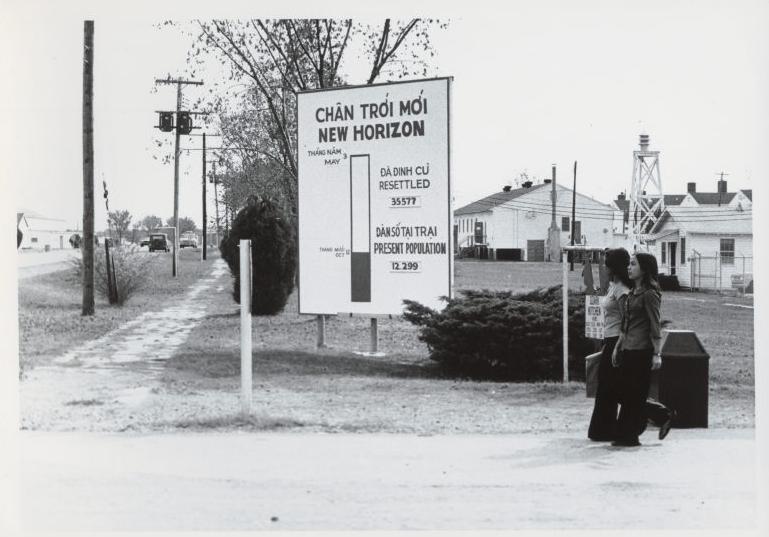

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

As the community faces more ICE raids and detentions, it appears that the Trump administration is not honoring the MoU—or the 1995 date it establishes. Advocates estimate the affected population—U.S. residents of Vietnamese origin, many of whom arrived as refugees, with removal orders—is over 10,000.

“The U.S. doesn’t seem to care about respecting the MoU as they just try to deport as many people as possible. We still don’t know if this will result in the ultimate deportation of those who came as refugees prior to 1995—that will be determined by the Vietnam government. But from what we can tell, this administration is pushing more aggressively for them to do it,” she says.

The fears wrought by this administration are par for the course, according to Dizon Mariategue. “All immigrants under Trump are living in constant fear,” she says.

Other advocates agreed.

“This confirms what we already know about Trump and this administration,” Huynh says. “Trump’s campaign promise was tied to separating families, to take a punitive approach to immigrants and refugees. The rescinding of DACA was coming and we knew that. … Now, it seems the U.S. is poised to step away from their 1995 agreement with the Vietnamese government as well.”

Many, like Orange County, California, resident Tung Nguyen, fear the Trump administration will ramp up efforts to separate Vietnamese families.

Nguyen, now 42, was a permanent U.S. resident when he says he fell in with the wrong crowd. He was convicted of charges related to a fatal robbery committed when he was 16 and ended up serving close to two decades at San Quentin State Prison. He was released in 2011 thanks to an executive order from Governor Jerry Brown. But as a non-citizen convicted of a crime, he was still subject to a removal order.

Now, Nguyen has a wife and child, and he is a vocal advocate against the school-to-prison pipeline that appears to funnel the children of underserved communities like his own into cyclical interactions with the justice system. In the little over six years since his release, he founded Asians and Pacific Islanders Reentry of Orange County, an organization that aims to address the stigma and other barriers that keep former prisoners from integrating back into their societies—and that lead, ultimately, to recidivism.

Many in the Southeast Asian-American advocacy community consider Nguyen to be a leading authority on and champion of the rights of former inmates, in particular juvenile delinquents. But with a final removal order, he worries his days may be numbered.

“Life is uncertain and fearful,” Nguyen says. “Uncertain, because you have no hope for the future—fearing for the day when I’m going to be torn from my family for something I did a long time ago, and I’ve paid my debt to society.”

Still, Nguyen remains hopeful. Dizon Mariategue’s SEARAC is advocating for members of Congress with voters in districts with large Vietnamese populations to denounce the deportations; Huynh is reaching out to his own community members. Together with other advocates, they are educating people about what to do when loved ones are detained for deportation.

“There’s sympathy in this country,” Nguyen says. “People give help when you ask for help.”