In the next installment of this series, conservation and restoration efforts on the Mexican side of the International Border will be explored. With less money and less water available, several nongovernmental organizations are busily dedicated to preserving key wetlands in the Colorado River’s Delta, as well as restoring riparian habitat along its corridor. In the third and final segment, cooperation between American and Mexican entities will be examined. The Colorado River conservation community is tight-knit, but there are transnational political considerations to be made when working with a natural resource that isn’t confined by political boundaries.

Part I: SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE

Part II: JUST ADD WATER: COLORADO DELTA RESURRECTS

Part III: THE RISKY BUSINESS OF SLICING THE PIE

Along its 1,450-mile length, the Colorado River crosses some of the wildest and most barren landscapes in North America, weaving through parts of Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, California, and the Mexican states of Baja California Norte and Sonora before emptying into the Gulf of California. With headwaters in northern Colorado and tributaries throughout its course, the river is fed by snowmelt and the terrific storms, which only occasionally slam the parched American Southwest, dropping thousands of feet in elevation before it snakes across the broad alluvial plain downstream from modern-day Lake Havasu.

Before the dawn of the 20th century, the Lower Colorado could instantly change from a mere trickle after dry summer months into a muddy, raging torrent, carrying tons of sediment from the dry terrain above, after a winter storm. Since that distant time, human progress — in the form of several massive dams — has put a chokehold on the once mighty river, and what was an unpredictable beast has been tamed into a vital asset to millions of acres of profitable farmland and tens of millions of urban water customers.

The river’s drastic transformation began during the first half of the last century, starting with the institution of the Colorado River Compact in 1922 — a complex agreement between states in the river’s water shed dividing its resources: essentially dividing the river into two basins — the Upper Basin covering Utah, Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico, and the Lower Basin encompassing California, Arizona and Southern Nevada. Based upon an estimated average annual flow of 17.5 million acre-feet per year, each basin received 7.5 million acre feet annually in the Compact, with an extra 1 million thrown in for obstreperous California Compact conference delegates, and 1.5 million acre-feet set aside for Mexico.

Although the average annual flow projection sounded good at the time, it may not have been realistic. Measurements taken at Lee’s Ferry, Ariz. — the spot arbitrarily selected to take the measurements ensuring the Lower Basin was getting its fair share — since 1921 indicate that the average annual flow has steadily decreased over the years as use has been ever on the rise.

Next came the construction of several monumental dams. Hoover Dam — which, when it was completed in 1936, was the largest dam and reservoir project in the world — was the first big dam erected on the river. Over the next 30 years, two more large dams — including Glen Canyon Dam, completed in 1966, standing at a height close to that of Hoover, but with a much greater width — and several smaller diversion dams for agricultural operations in California’s Imperial Valley were completed. On the Lower Colorado River, this has meant nearly 58 million acre-feet of water storage capacity and almost 4 million kilowatt hours of electricity production from the hydroelectric turbines included in dam construction.

While harnessing the Colorado’s resources has fueled development in the booming Southwest, at the same time putting an end to the damaging floods that once ravaged flat sections of the river’s course, as well as putting into existence some of the most magnificent dams ever built by humankind, there has been a cost. Today, nearly every drop of the river’s water is spoken for, sometimes above what’s actually available, leaving little for the once teeming ecosystems along the banks of the river’s lower reach.

The Colorado River Delta, once an immense wetland the size of Rhode Island and the most important stopover along the route of migratory waterfowl in North America, has shriveled to a tenth of its original size. Cottonwood, willow and mesquite, which a century ago shaded river banks, have largely disappeared with the water; nonnative, and very hearty, salt cedar has taken their place. Insects, birds and fish that were common are now more difficult to find.

But as the dams were built and the waters diverted during the 20th century, the seeds of a greater awareness of the river’s resources were planted. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the agency largely responsible for most of the damming and diversion, began to listen to a growing amount of scientific study and popular discontent directed at the dams’ environmental impacts.

Many educational institutions, nongovernmental organizations and government agencies on both sides of the international border have a hand in habitat conservation and restoration efforts along the banks of the Colorado River. But the Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado River Multi Species Conservation Program — better known in bureaucratic lingo as MSCP (pronounced “em-skeep”) and covering a reach of the river stretching nearly 300 miles from the International Border to the upstream edge of Lake Mead — is perhaps the largest and best financed effort currently in place.

Since its initiation in 2005, MSCP overshadows the spending of any other conservation or restoration program. According to a Congressional Budget Office report, the program will receive approximately $70 million over the next five years alone, with nearly $600 million more over its 50-year lifespan. Its budget includes federal dollars already allocated to the bureau by Congress as well as money from state wildlife management agencies, which cover half of the overall cost. Of the states’ portion, California pays 50 percent, and Nevada and Arizona 25 percent each. The Bureau of Reclamation is the program’s lead agency, but there are more than 50 entities involved, including university research groups, farm advisory boards and other federal agencies.

Some form of conservation activity has been going on along the river’s lower reach since the 1970s, when the Bureau began dredging oxbows lakes — long disconnected from the river’s main stem — to create waterfowl habitat.

But MSCP is the first attempt to find ecological solutions that work within the big-picture context of intense irrigation and urban water supply demands. “Even before the MSCP, we had MSCP-like activity,” said Terry Murphy, the program’s Restoration Group manager based out in Boulder City, Nev., office. “Lots of people divert water from [the Colorado River], so reasonable goals have to be set for wildlife conservation over the next 40 to 50 years.”

The program’s stated goal is to preserve 26 species, a list that includes native plants, mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and invertebrates, among the more charismatic animals like the red western bats, southern willow flycatchers and razorback suckers. Conservationists hope the species targeted by the project will be bolstered by 8,132 acres of restored habitat called for in the plan.

“The way I would look at it is advanced mitigation. Basically, this will take care of the potential impacts of continued river operations,” said Murphy, highlighting fish augmentation, species research, system monitoring, habitat creation and existing habitat protection as the program’s main tenets.

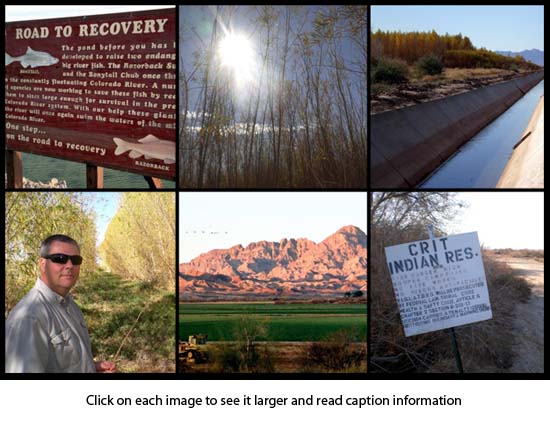

There are 14 conservation areas scattered up and down the Lower Colorado River, and each one is unique. Murphy pointed out when he took this reporter on a tour of some of the project sites near Blythe, Calif., that different places have different needs, based on the topography, water table, wildlife, the people living nearby and myriad other considerations. Most are fed with water from nearby irrigation districts, and depending upon the plants being established, different irrigation techniques are used.

At one such site, the Palo Verde Ecological Reserve, several different methods of growing cottonwood trees are used. The trees are evenly planted in close rows on one plot. On another, cottonwoods, mesquites and willows — the main type of tree needed for this type of habitat — are planted together to see how they fare among one another. One thing that Murphy’s team and its partners have found is that salt cedar tends not to supplant native plants, but fills in after lack of water kills them.

Downriver a few miles, nestled in a bend on the Arizona bank, is the Cibola National Wildlife Refuge. Although owned and operated by the National Fish and Wildlife Service, there are several large plots dedicated to MSCP restoration projects.

“At this scale, you really have to run this like a business, like a farmer would — break it up into manageable chunks and keep it going,” said Murphy. He added that forming relationships with farmers and other federal agencies working in the area relieves some of the pressure from his seven-person Boulder City-based staff. The scale of their collective efforts could be seen as he pointed out distant stands of trees at various stages of growth set against a backdrop of jagged brown mountains. They are the result of planting operations that have been going on since before MSCP was instituted.

Several miles back up the river, just outside the impoverished town of Ehrenberg, Ariz., lies a huge tract of federal land owned by the Colorado River Indian Tribes. This land is administered by the federal bureaus of Indian Affairs and Land Management, but the MSCP is working to restore stands of mesquite among the unsightly tangle of salt cedar that has filled in. Not only do residents occasionally use mesquite cuttings for ceremonial purposes, but the salt cedar creates a layer of fluffy detritus that has led to more wildfires.

With huge swaths of land staked out for restoration, there is still much for the MSCP to accomplish and many ways for each area to be approached. Once all of these now-barren patches are planted, the project will be able to focus more heavily on making the work that has been finished last.

A big question that pops up when considering the Colorado River water scenario is how all of this affects Mexico, which lies at the end of the river’s long course, and is, by treaty, guaranteed 1.5 million acre-feet of water every year to feed the fertile desert farmland and bustling population centers just south of the border.

“It really doesn’t affect their water at all. What was growing alfalfa last year is growing trees this year,” said Murphy, explaining that the bureau has to buy its water rights like everyone else. “We like to think that it’s more beneficial to the entire river corridor because it provides habitat for all the species that use it.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.