Paul Nyden, a longtime investigative reporter at the Charleston Gazette, used to say he had two tenets that guided his work. The first was: “Figure out who the bad guys are, and fuck ’em.” And the second was: “Then fuck ’em again.” Not exactly what they teach in J-school. But in West Virginia, where the entire arc of the state’s history has been perverted by a seemingly endless run of bad guys, it’s not only a justifiable approach to journalism; it’s an essential one.

Guys like Johnson N. Camden, one of the state’s founding fathers, who sold out to Standard Oil in the 1870s and then conspired with John D. Rockefeller Sr. to crush West Virginia’s nascent refining industry, before retiring to a private island off the Florida coast. Or William MacCorkle, a son of the Confederacy who got rich helping outside investors get control of the state’s timber and mineral wealth (“I smiled, and the money came,” he wrote in his memoir), then exploited racial fears to get elected governor in 1892.

Or, more recently, Governor Wally Barron, who went to prison in 1971, for—stick with me here—bribing the jury foreman during an earlier trial on charges of, yes, bribery, of which he had been acquitted. Or Arch Moore, the three-term governor who was dogged for years by corruption allegations, and who finally was put away (thanks in part to Nyden’s reporting) in 1990 after pleading guilty to five felonies, including extortion and obstruction of justice.

Losing the News, by Brent Cunningham. Listen to more Pacific Standard stories, read out loud.

L.T. Anderson, a columnist who worked at both the Gazette and its afternoon rival, the Charleston Daily Mail, liked to say that state officeholders would “take hemorrhoids if they were being given away.” Such disregard for the commonweal among those in power helps explain West Virginia’s enduring place at or near the bottom of so many measures of prosperity, from rates of poverty and tobacco use to obesity and drug overdoses. Whether Nyden meant his creed in earnest, or as merely a bit of bravado uttered late at night in the smoky confines of the Red Carpet Lounge, the bar in the shadow of the capitol building where reporters and pols mixed off the record, is beside the point. The reason those lines became part of Charleston’s journalism lore is because they distilled, in thrillingly profane fashion, what the Gazette stood for.

In the waning decades of the 20th century, the Gazette was the state’s alpha watchdog, going after the coal industry—the dominant economic, political, and cultural force—and the corruption and environmental abuse that accumulated in its wake, with persistence and ferocity. Led by publisher W.E. Chilton III, the Yale University-educated scion of the family who had owned the paper since 1907, the Gazette‘s unofficial motto, which Chilton coined in a 1983 speech to the Southern Newspaper Publishers Association, was “sustained outrage.” Chilton, known to all as Ned, was a cantankerous liberal, unapologetically so. He was an early champion of racial equality, denounced capital punishment as “legal murder,” and was willing to lash the pillars of local advertising, such as car dealers (in a series called “Ripoff?” that found evidence of odometer tampering) and realtors (accusing them of “bigotry” when they sought to block enforcement of fair housing laws). Until his death in 1987, at age 65, Chilton wielded the Gazette‘s editorial page like a cudgel against anyone and anything that ran afoul of his uncompromising sense of right and wrong.

(Photo: Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Getty Images)

Not surprisingly, Chilton and the Gazette made a lot of enemies. Even before his conviction, Governor Moore referred to the paper as “the morning sick call.” Complaints that it was “too negative,” “too liberal,” and an impediment to economic development, have simmered for decades among the business and political establishment—a sentiment that has sharpened in recent years, as the state turned from solid blue to the reddest of reds, handing the legislature to the GOP for the first time since 1930, and giving Donald Trump nearly 70 percent of its votes.

Nyden, who retired in 2015 when the Gazette and the Daily Mail merged, died of a heart attack on January 6th, 2018, at age 72. It was nine months after the Gazette-Mail won a Pulitzer Prize—its first for reporting—for a Nyden-esque investigation of the ocean of prescription opioids pumped into the state by pharmaceutical giants, and just weeks before the paper filed for bankruptcy, felled by debt and plummeting ad revenue. (The announcement prompted a coal-industry lawyer to publicly mock the Gazette-Mail‘s star environmental reporter, Ken Ward Jr., suggesting he might soon be unemployed.)

A little more than a month later, the Chiltons sold the paper to a group of investors for $11.5 million, ending more than a century of family ownership. Some of the new owners, including the lead investor, Doug Reynolds, a businessman with political ambitions, have financial ties to the natural gas industry. As coal fades, natural gas is being hyped as the “cleaner” fossil fuel (a debatable claim) that can fill the economic void and usher in a new era of prosperity in the Mountain State.

I grew up in Charleston and began my journalism career there. When I visited last summer, the extreme swings of fortune at the Gazette-Mail—from the Pulitzer to the auction block in less than a year—had people wondering about the paper’s fate. What kind of newspaper did the new owners want? Would “sustained outrage” be replaced by something more complacent? And if so, what would that mean for the future of West Virginia?

The concern was understandable. The Gazette-Mail bankruptcy was another chapter in the protracted decline of local journalism in America that has played out over the last 20 years. As digital media undercut the advertising-based business model that had supported newsrooms for more than a century, newspapers across the country shed reporters and lowered their ambitions as they searched—so far in vain—for a solution. “Do more with less” became the industry’s pitiable battle cry. When the Great Recession hit, private equity funds, pension funds, and other investment partnerships began buying up these “distressed assets,” squeezing out profit by strangling what remained of the newspapers’ public-service muscle—the accountability journalism that kept readers aware of what the powerful were up to in their communities. Between 2007 and 2015, the number of full-time daily newspaper reporters in America dropped 40 percent, from 55,000 to 32,900.

(Photos: Unsplash & Getty Images; Illustration: Ian Hurley/Pacific Standard)

That loss of coverage has been described, without exaggeration, as a threat to democracy. In November of 2018, a trio of political science and communications professors published the findings of a long-term study of communities where local newspapers have died. They found that, as local papers close, political polarization grows, and accountability in the public sphere may shrink. “Residents of cities without sources of local news are losing their ability to hold their political representatives accountable in ways that encourage ethical and effective representation,” said Johanna Dunaway, one of the study’s authors.

Doug Reynolds sees opportunity in this decline. “When things are bad in an industry, that’s the time to get in,” he told me. In 2013, he launched HD Media, which now owns half a dozen other newspapers in the state besides the Gazette-Mail, including the Herald-Dispatch in Huntington, the state’s second-largest city. But Reynolds insists there is no plan to strip these papers; to the contrary, he says he will “grow” the Gazette-Mail newsroom once he shores up the paper’s finances. “The truth of it is, we could lay off half the newsroom tomorrow, and our profits would go up the next day,” he said. “But over time, it would be a bad business decision.”

Everything, it seems, is a business decision to Reynolds. When he bought the Gazette-Mail, he laid off 11 people—four from the newsroom, including the executive editor, leaving 42 employees. Since then, several people have left, and those vacancies have not been filled. “We had to get sustainable with the revenue we got,” he told me. “Newspapers are first and foremost a business.”

We were sitting at a conference table in the old Daily Mail newsroom, across the hall from the Gazette-Mail. The newsroom, vacant since the merger in 2015, was eerily intact—including the cubicle where I sat a quarter of a century earlier—like a scene from one of those day-after films. It was the end of June, and the air outside was heavy with the promise of a thunderstorm. It was heavy, too, with more political chicanery: the legislature had begun debating whether to impeach “one or more” of the state’s Supreme Court justices, and a mysterious scandal was brewing involving $150 million in federal flood relief that, as one reporter put it, got lost in the “blender of state bureaucracy” and was never spent on what it was intended for—replacing or repairing homes lost to a flood in 2016 that killed 23 people. The whole town felt weary.

(Photo: Ty Wright/Getty Images)

Reynolds, though, exuded confidence. His face was thin and boyish, his sandy-blond hair clipped short. He had spent a decade in the legislature, lost a bid to be attorney general in 2016, and had been mentioned as a possible candidate for higher office. His father is Marshall T. Reynolds, the tobacco-chewing tycoon from Huntington, where Doug was born. The elder Reynolds rose from working-class roots to build a business empire that includes banking and real estate. And he did it by bucking the stuffy establishment in Huntington, where who one’s father is has historically mattered more than anything else. So there is affinity for the striver in Doug Reynolds’ DNA.

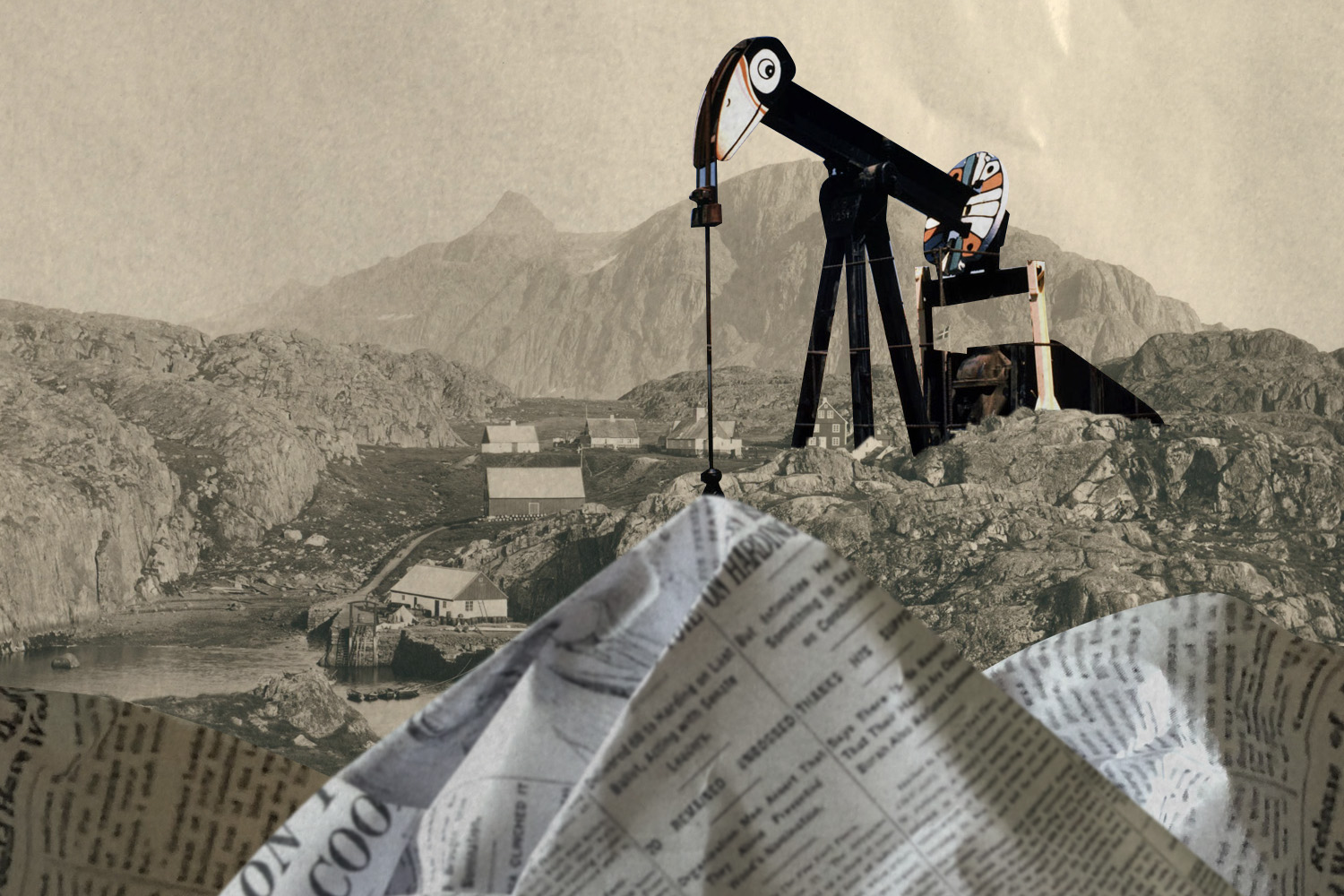

I asked him to describe his journalism philosophy, and he did so in a single sentence: “You’ve got to kind of balance what people want to hear with what they need to hear.” It wasn’t “sustained outrage,” but it wasn’t the rapacious indifference of the vulture capitalists either. Finding that balance, never easy, will be even harder in a newspaper business that continues to struggle. It will be harder still given that Reynolds is entangled in what could be the biggest economic shift in the state since industrialization: the pursuit of shale gas.

West Virginia sits atop a large swath of the Marcellus Shale, the 400-million-year-old rock formation that stretches across the Appalachian Basin and is one of the largest reservoirs of recoverable gas in the country. Since the mid-2000s, energy companies have been tapping the Marcellus, using a combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking, for short) to pump water, sand, and chemicals into the ground to free gas from deposits that were previously thought unreachable. Thanks to this new technology, natural gas production in West Virginia surged more than five-fold in less than a decade, from more than 240 billion cubic feet in 2008 to nearly 1.4 trillion cubic feet in 2016.

This is the most important story Doug Reynolds’ papers must cover, one that is likely to shape the post-coal future of the state. And it is a story in which Reynolds is a player on both sides. In addition to owning his newspapers, he is president and chief executive officer of Energy Services of America, which makes natural-gas pipelines. Brian Jarvis, another principal in the group that bought the Gazette-Mail, also is a two-way player. He is president of NCWV Media, which owns newspapers in the north-central part of the state, and also of Hydrocarbon Well Services, an oil and gas service operation.

Some of the biggest energy companies in the country are chasing gas in West Virginia, including Pittsburgh-based EQT, Denver-based Antero Resources, and Richmond-based Dominion Energy. There are several major pipelines underway and numerous smaller projects. In the fall of 2017, as part of President Trump’s trip to China, West Virginia signed a memo of understanding for China Energy to invest $83 billion over 20 years in the state’s natural gas infrastructure. “For crying out loud, it absolutely takes your breath,” gushed Governor Jim Justice, a billionaire who was elected in 2016 and who touts his friendship with Trump, over the size of the China deal. His administration has refused to release the details of that memo.

The grand vision, according to gas proponents, is that the boom will revitalize the state’s chemical industry, which thrived in the middle of last century when the region around Charleston was known as “Chemical Valley.” Plants run by Union Carbide, Monsanto, and others made everything from Agent Orange to methyl isocyanate (the stuff that killed thousands in Bhopal, India, when it leaked in 1984) and employed some 40,000 people in towns up and down the Kanawha River with names like Alloy and Nitro. What the backers of this vision are less interested in recalling is how effluent and emissions from those plants fouled the river; tainted the air, soil, and groundwater; and did untold damage to the health of residents. Leaks and explosions, sometimes fatal, were not uncommon. But the local economy grew, and in West Virginia such collateral damage has always been the price of development.

There is a lot of money on the table, a lot of big talk, and a lot of competing interests swirling around the current gas boom. It is at this point when things have often gone cockeyed in West Virginia. Some things already have. In 2017, Bray Cary, a local businessman, joined the governor’s administration as an unpaid “citizen volunteer.” At the time, Cary sat on the board of EQT, the Pittsburgh-based energy giant that is the second-largest producer of gas in West Virginia, and he is also a major stockholder in the company. Yet it was only after the Gazette-Mail raised questions about his role in the administration that Cary was made to sign a non-disclosure agreement. State lawmakers, acknowledging the myriad potential problems with this situation, passed the so-called Bray Cary bill, requiring “public servant volunteers” who work in official capacities in the government to file ethics disclosures.

But it remains the case that a guy with close ties to, and a financial stake in, a multi-billion-dollar energy company that intends to make a lot of money in West Virginia is whispering daily in the governor’s ear. What could go wrong?

The debate over economic development in West Virginia, and particularly the role of extractive industries, is an emotional one with a deep and troubled backstory. Coal has defined West Virginia for more than a century, giving tens of thousands of people a livelihood and an identity. As a friend who mined coal for 13 years said to me, “Coal put my kids through college.” But it also gutted the state physically, shortchanged it economically, and left a legacy of environmental ruin, shattered communities, and shattered bodies. It’s hardly a stretch to see how the rush to shale gas, which has been shown to pollute both surface and groundwater, could end in a similarly dismal cul-de-sac.

If there is one person who embodies the complexity Reynolds faces in trying to strike the balance he seeks in the Gazette-Mail‘s coverage, it is Ken Ward Jr., the paper’s 51-year-old environmental reporter. Ward, who grew up in a manufacturing town in Mineral County, near the Maryland border, joined the Gazette in 1991. Four years earlier, when Ned Chilton died, the outpouring of tributes contained a note of anxiety that corruption would flourish in the state without him to keep it in check. “If it had not been for Ned Chilton,” one law-enforcement official said at the time, “the politicians would have carried away the statehouse, the courthouse, and city hall.” But Ward, as much as anyone, helped ensure that “sustained outrage” continued to define Gazette journalism. He embraced Paul Nyden’s belief that journalism’s highest calling was not some feckless notion of “objectivity,” but rather to follow the paper trail and expose the many ways the powerful exploit the powerless. Fuck ’em, in other words, but do it with the facts.

Over the next 20 years, Ward gained national prominence for his reporting on mine safety and the environmental costs of coal; among industry leaders and their political allies, he gained a reputation as a major pain in the butt.

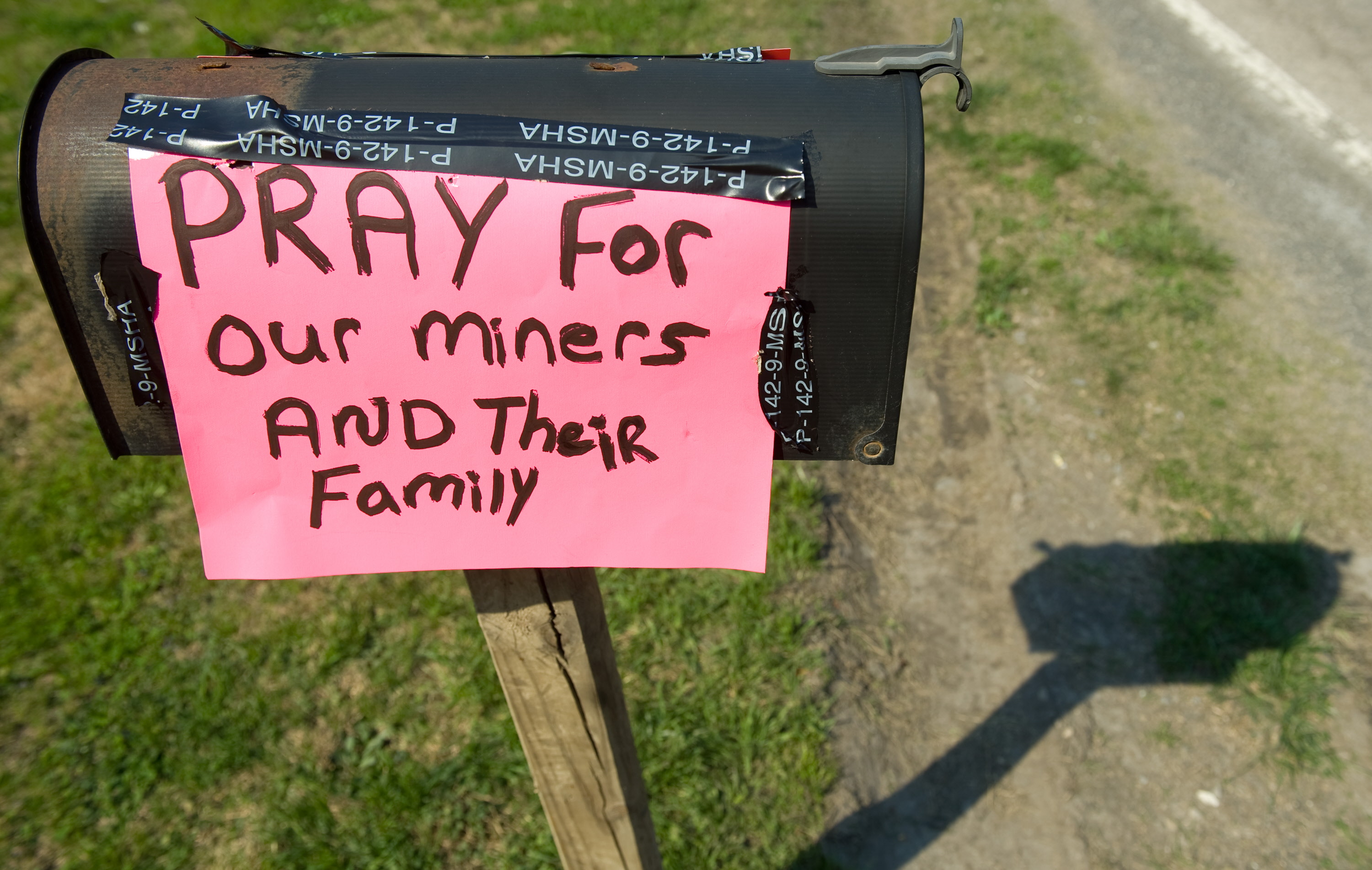

Then, on April 5th, 2010, an explosion at Massey Energy’s Upper Big Branch mine in southern West Virginia killed 29 miners. It was the country’s deadliest coal-mining disaster in 40 years. The ensuing investigation described a culture of disregard for safety and environmental regulations within Massey, the nation’s fourth-largest producer of coal at the time. Eighteen corporate officials refused to cooperate with the investigation, invoking their Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination.

(Photo: Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images)

What happened at Upper Big Branch was the culmination of the state’s legacy of corruption—a choice made a century earlier to surrender its soul to the coal industry, underfunding regulatory enforcement even as it made endless concessions to coal’s economic, political, and cultural power. It also was the start of a six-year-long story that was unprecedented in the state’s history, one that resulted in Don Blankenship, the Massey chief executive officer and a powerful figure in the state and beyond, going to prison for conspiring to violate safety and health standards.

And it was a story for which Ward had been preparing since he started at the paper. The entire media ecosystem seemed to rely, to varying degrees, on his reporting and institutional knowledge during the days and months after the explosion. He even made a cameo, indirectly, at Blankenship’s trial, when prosecutors played a recording of Blankenship on the phone, less than a year before the explosion at Upper Big Branch, fretting about the prospect of a memo from one of his safety inspectors becoming public. The memo was damning, citing not just specific safety concerns but a culture of putting profit before safety. On the recording, Blankenship describes the memo as “worse than a Charleston Gazette article.”

But the piece of this story that means the most to Ward, that still causes his voice to crack years later, happened during one of the least consequential moments in the Blankenship saga. When the verdict was on appeal, Ward drove five hours to Richmond, Virginia, to hear oral arguments. “We don’t typically go to Richmond to cover trials,” he says, “but when I walked into the federal courthouse there, I saw some family members of the victims, and one of them saw me and said, ‘We knew the Gazette would be here.'”

(Photo: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images)

In 2018, Ward was selected for the inaugural class of ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network, an effort to support investigative journalism at smaller papers around the country by paying reporters’ salaries for a year, helping them develop stories around a theme, and then co-publishing those stories. Ward’s project was to scrutinize the state’s natural-gas boom from a provocative standpoint: Is West Virginia making the same regulatory mistakes with gas that it made more than a century ago with coal? It was a line of inquiry Ned Chilton would have applauded.

In an early story for the project, Ward got right to the point: “Elected officials have sided with natural gas companies on tax proposals and property rights legislation,” he wrote. “Industry lobbyists have convinced regulators to soften new rules aimed at protecting residents and their communities from drilling damage.”

The litany of ominous decisions about the regulation of fracking that Ward unpacked was depressing, from Governor Justice vowing, in his first state-of-the-state address, that his Department of Environmental Protection would stop saying no to business and industry, to the governor’s hasty retreat, in the face of industry complaints, from the idea of hiking the severance tax on natural gas to give striking teachers a pay raise. It also was depressingly familiar. As Ward notes, miners, too, were promised prosperity, but “today some of the places that have produced the most coal are among the region’s poorest.”

It can sometimes seem that, if it weren’t for Ward, no one would be pointing all this out. In August of 2018, for example, federal courts halted work on two major pipelines being built through West Virginia after finding that several agencies had failed to follow environmental regulations when approving the projects. Ward, along with two other reporters, dug into the record and produced a story that showed that federal and state watchdogs tasked with enforcing environmental laws had “moved repeatedly to clear roadblocks and expedite” the pipeline projects. Two days later, a website for some of the papers owned by Gazette-Mail investor Brian Jarvis weighed in with a story that assured readers the pipelines were moving forward, despite the temporary setback; and the Exponent-Telegram, another of Jarvis’ papers, published an editorial warning that “lengthy delays could cost the state a future residents richly deserve and throw us further behind our neighbors.”

When I asked Reynolds about Ward’s series, he called it “the most important thing we’ve done in my short time here. There’s a huge change happening, and an incredible amount of wealth is being created. So the logical question is, where are we going to be at the end of all this?”

And what about Ward’s contention that the state could lose out on its fair share of that “incredible wealth” the gas boom is generating, as it did with coal?

Reynolds paused before he answered. “There is not a doubt in my mind that the state, in this current environment, will take less than other states are going to take.”

Why? “Because the people who run the gas industry have more influence here,” Reynolds said. “The public decides the kind of people they want running the state. They want less regulation, less environmental regulation—things that both Governor Justice and President Trump talk about all the time. No one has won elections in West Virginia lately saying they’re going to make sure these mining permits are held to the highest standard.”

The most obvious effort so far to “balance” the kind of reporting that Ward is doing with more positive coverage is a new weekly section called Daily Mail WV. It launched in June of 2018, designed to appeal to potential readers and advertisers who either think the rest of the paper is too liberal or anti-business, or who just miss the Daily Mail. After the merger, a few thousand Daily Mail subscribers dropped out, and overall circulation continued to decline; it was enough to convince Reynolds and his team that the Daily Mail brand still had value.

The Charleston Daily Mail, where I worked from 1990 to 1994, entered a joint operating agreement with the Gazette in 1958, which meant the two papers shared advertising and circulation services, as well as a building. The Daily Mail was the more conservative paper, particularly on the editorial page. The newsrooms were sharply competitive. Separated by a hallway, we had different cultures, different physical vibes. At the Daily Mail, a dress code mandated coats and ties, while at the Gazette jeans were fine. Our newsroom was bright and airy; the Gazette‘s was cavelike, dug-in. The desire to outdo your counterpart fostered a vibrant news culture that surely benefited readers. It was the tail end of the good years for daily newspapers. Watergate remained a palpable touchstone of great journalism; the Internet was a few years off. And the idea that Charleston, West Virginia, still had competing dailies was a point of pride.

Kelly Merritt, a former public-relations guy who edited the new section during its first 10 months (he left in March for a job with a gas company), said the idea was to evoke something of the old Daily Mail, particularly its business features. “The spirit of those features was being open to looking at anything in a positive light, not always from the standpoint of ‘somebody’s out there doing something bad, and we’re going to catch ’em by golly.'”

The Daily Mail I knew wasn’t a fire-breathing crusader like Chilton’s Gazette, but it was a good newspaper that produced its own brand of watchdog journalism, winning a Pulitzer for editorial writing in 1975. I don’t recognize much of that paper in Daily Mail WV, which offers a mix of business-focused opinion pieces and features that is singularly bullish on the future of West Virginia.

The first installment featured Governor Justice assessing, “in his own words,” his first two years in office. Unemployment in West Virginia is among the highest in the country, at 4.8 percent; it’s one of only a very few states where the poverty rate has risen in recent years; and, according to a 2017 report, the state has the third-highest percentage of residents living in “economically distressed” zip codes. Yet the governor was allowed to proclaim, without contradiction: “The goodness is just going to come and keep coming. … It is truly unbelievable what’s happening.”

(Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Once the governor set the tone, the section went on to address, among other things, the gas boom’s potential to revive the chemical industry (of course); the importance of commercial river traffic in the state (including a half-page ad from the main source in the lead story and a “hats off” editorial to that source); and the governor’s road-building program (with two stories that quoted no critics of the program, and a full-page ad from the Contractors Association of West Virginia saying how great the program is).

An issue on recycling celebrated A. James Manchin, the late uncle of United States Senator Joe Manchin, for his work in the 1970s purging junked cars and appliances from the state’s hills and hollows. The column included only a couple of gently worded sentences about Manchin’s “fall from grace.” Allow me to fill in the picture. Manchin, who served as state treasurer from 1985 to 1989, was impeached for losing nearly $300 million from the state’s Consolidated Fund through bad investments, and then covering up the losses for a year, in part by falsifying records. (His assistant treasurer, Arnold Margolin, went to prison for lying about the losses and his role in the cover-up.) The special prosecutor who investigated the case said Manchin “would have had to be blind, deaf, and dumb not to have been aware … of precisely what was transpiring.” Yet that is what A. James claimed, insisting he was “a victim of the system.” Manchin was no hero. He was just another “public servant” who failed the state and its people.

There is nothing wrong with optimism in news coverage, when it’s warranted. But it’s hard not to see Daily Mail WV in the context of a broader rumbling about the need to counter negative perceptions of the state, to “change the narrative.” West Virginia has spent much of its life in a defensive crouch, poised to take offense at every insult hurled its way, of which there have been many. More than most, the state has been defined by negative stereotype—some of it earned, much of it not: the ignorant hillbilly, the book-banning xenophobe. Of late there has been an increasingly audible retort, mostly from a crop of community-media start-ups, that focuses on stories of reinvention and progress (#uplift).

I sympathize. But I also see how good-faith efforts to complicate the simplistic portrayal of West Virginia in the national media play into Governor Justice’s persistent haranguing of the Gazette-Mail to be more positive. Like Trump, the governor lashes out at any critical story—about his failure to put his billion-dollar businesses into a blind trust, or the history of safety violations and unpaid fines at his coal mines, or the millions in back taxes he owed. He obsessively berates the paper and its reporters. By ignoring this kind of “negative” context, stories like those I described in Daily Mail WV give cover to incompetence and claims of “fake news.”

Reynolds, of course, describes the new section in business terms. He needed revenue fast, and this section provided some—more than $15,000 worth of advertising in the first 11 weeks (compared to less than $1,000 in the two months prior for the section it replaced). “The goal was not to create an anti-Gazette section,” he says. “We’re going to try new things. I’d do a section on rabbits and bunnies if enough people who care about rabbits and bunnies would support it.”

The day after my meeting with Reynolds, I sat in the balcony in the House of Delegates chamber, listening to lawmakers debate the timing of their impeachment investigation into the Supreme Court justices for a range of ethical violations, including elaborate office renovations and misuse of state vehicles and other property. The capitol building, designed by the architect Cass Gilbert, is impressive, its soaring, gilded dome gazing down across a gentle bend in the Kanawha River. But the cool limestone facade and marble corridors always struck me as jarringly mismatched to the lowbrow bullshit that too often transpired within.

(Photo: O Palsson/Wikimedia Commons)

I thought of all the hours I spent in that chamber listening to tedious and inelegant debates, full of righteous claims about “serving the good people of West Virginia.” To be sure, I covered some elected officials who tried their best to do just that. But my time at the Daily Mail overlapped with a spate of public corruption unmatched until, perhaps, this current one. It wasn’t just Arch Moore and A. James Manchin who went down back then, but two successive senate presidents (for extortion) and the head of the state lottery and the lottery’s attorney (for insider trading). Sammy D’Annunzio, a powerful lobbyist who was neck-deep in the statehouse corruption, committed suicide. Good times.

Later, I walked over to the Red Carpet, sweating through my shirt in the steamy afternoon heat. Little had changed there either. Same squat, gray cinderblock box, no windows. I even ran into a couple of people I knew from the old days. Inside, bathed in the dim glow of video gambling machines, the Carpet was still the kind of bar where you could forget what time of day it was—pleasantly so. The beers were still cold and cheap, and before long I was thinking about the past—mine, but also West Virginia’s.

It occurred to me that in all of this—the hyping of natural gas, the clamor for “positive” news—there was more than a whiff of the happy talk that reverberated through West Virginia in the late 19th century, as the new state was quickly being turned into a fuel depot for the Industrial Revolution. The men who built the state insisted that West Virginia, rich with coal and timber and located near the emerging industrial centers of the Northeast and Midwest, was destined to prosper.

J.H. Diss Debar, a land speculator and designer of the state seal who later went to prison for running a confidence game, captured the sentiment with carnival-barker aplomb in an 1870 treatise on the state’s virtues: That “a State … so full of the varied treasures of the forest and the mine … should lack inhabitants, or the hum of industry, or the show of wealth is an absurdity in the present and an impossibility in the future.”

(Photo: Justin Merriman/Getty Images)

That sounds not unlike this bit of puffery, circa 2013, from Earl Ray Tomblin, who preceded Jim Justice as governor: “The shale development and the potential economic growth and jobs that will come with the revitalization of the manufacturing sector are astounding; and West Virginia is right at the center of it all.”

From the start, West Virginians lacked the money they needed to develop the mines and timbering operations for themselves. That’s why Johnson Camden, Governor MacCorkle, and their ilk rigged the political and judicial systems to suit the out-of-state money men. This lack of homegrown capital remains a problem in the gas-boom era; that’s why the big projects are led, once again, by out-of-state companies. The past is never very far away in West Virginia.

In August of 2018, the Republican-controlled House of Delegates voted to impeach all four of the remaining Supreme Court justices. The former chief justice, who—no joke—once published a book decrying the history of political corruption in West Virginia, also was indicted on 22 federal charges, including fraud and witness tampering. A fifth justice, who resigned before he could be impeached, pleaded guilty to wire fraud. Democrats claimed the wholesale impeachment was a political ploy by Republicans to remake the court. Maybe it was. The senate trials were tragicomic, the whole thing a disgrace.

This year, the legislature adjourned without even granting a hearing to a handful of bills that sought to address residents’ concerns about air, water, and noise pollution caused by the gas boom. And EQT, the energy giant, agreed to pay $53.5 million to settle a lawsuit that claimed the company was cheating thousands of state residents and businesses on royalty payments—even as a new report found that the economic windfall promised by gas proponents was overhyped.

At the Gazette-Mail, meanwhile, the post-Chilton future is becoming visible. ProPublica renewed its partnership with Ken Ward for a second year; Report for America, which places journalists in underserved areas, also renewed the reporter it had at the paper last year and added a second one to cover poverty in southern West Virginia; there is a Gazette-Mail podcast; and digital subscriptions are up more than 40 percent from last year, goosed by a temporary deal of 99 cents a month. However, news of at least one additional layoff followed in July.

Doug Reynolds is not Ned Chilton. But maybe Ned Chilton wouldn’t be the same newsman today as the one we celebrate. After all, Chilton’s conviction that a newspaper’s pursuit of profit could and must coexist with its commitment to public service is a far more difficult proposition now. Reynolds is clear that he intends to profit from journalism. And he seems fine with the public-service end of that equation, as long as it can be monetized. “The bottom line,” he told me, “is I don’t care if people are happy or sad about our coverage, as long as they aren’t ambivalent.” Maybe that’s the best we can hope for these days.

I worry, though, that it won’t be enough. West Virginia is at a crossroads. With coal in decline, the state has a chance to diversify its economy, to build a future that is environmentally sustainable, one in which opportunity and prosperity are more broadly shared. But for that to happen, it needs leaders who actually put the public interest first—and a vigorous watchdog to make sure they do.

In his 1976 history of the state, John Alexander Williams explained the problem this way: “West Virginia … remained the way it was because the most powerful West Virginians liked it that way.” There’s an unsettling echo of that sentiment in Reynolds’ comment about the undue influence of the gas industry among the state’s power brokers. And that is the narrative that has to change. Until it does, all the “positive” media coverage in the world won’t make a difference in West Virginia’s economic fortunes, or in the fate of its people. What might, though, is journalism that’s brash and unsparing—maybe even a little outraged. ❖

Author: Brent Cunningham is executive editor of the Food & Environment Reporting Network and a former deputy editor at the Columbia Journalism Review. From 1990 to 1994, he was a reporter at the Charleston Daily Mail.

Illustrator: Imogen Todd is a designer currently based in Washington, D.C. In addition to freelancing, she works as a UX and data visualization designer. She attended Carnegie Mellon University, where she studied human-computer interaction, decision science, and design.

Editor: Ted Genoways

Researcher: James Gaines

Picture Editor: Ian Hurley

Copy Editor: Leah Angstman

This story is part of the Unseen America project, stories about the struggles and challenges being faced by the misunderstood middle of our nation.