I am writing this a few hours after the World Health Organization raised the influenza pandemic alert level from 4 to 5, the second highest level, because “a pandemic is imminent.” This means that there is human-to-human spread of the virus into at least two countries in one WHO region.

But while the virus spreads quickly, information about the virus spreads even faster than the virus itself. By now, almost everyone with access to a news source is aware of swine flu, and people are worried to different degrees and react in very different ways. My colleagues and I who study the spread of infectious diseases would like to know what people think about swine flu, how they feel about it, and how they will eventually react. To achieve this goal, we have created an easy online (and anonymous) survey, which I cordially invite you take. Let me give you some background info on why we believe this is important.

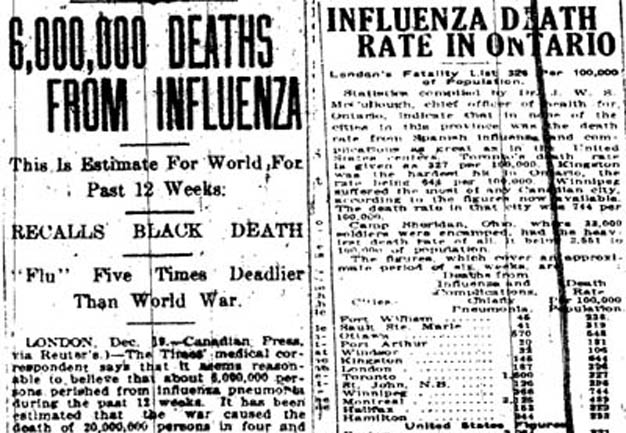

Swine flu is neither the first nor the last virus that we will have to deal with. Last year, a research team reported 335 infectious diseases emerged between 1940 and 2004. Ideally, a disease can be prevented from spreading in the first place, but as we are experiencing now, this is not always possible.

Once there is widespread human-to-human transmission, there are essentially two broad classes of strategies to stop or mitigate a pandemic: pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical. The two main pharmaceutical strategies to combat a spreading virus are vaccines and antiviral drugs, but those are not always readily at hand: Vaccine production is a time-consuming process, and a number of viruses are resistant to some or all of the currently available antiviral drugs.

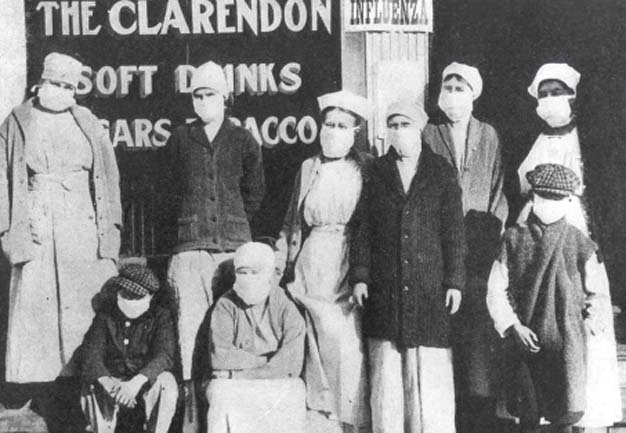

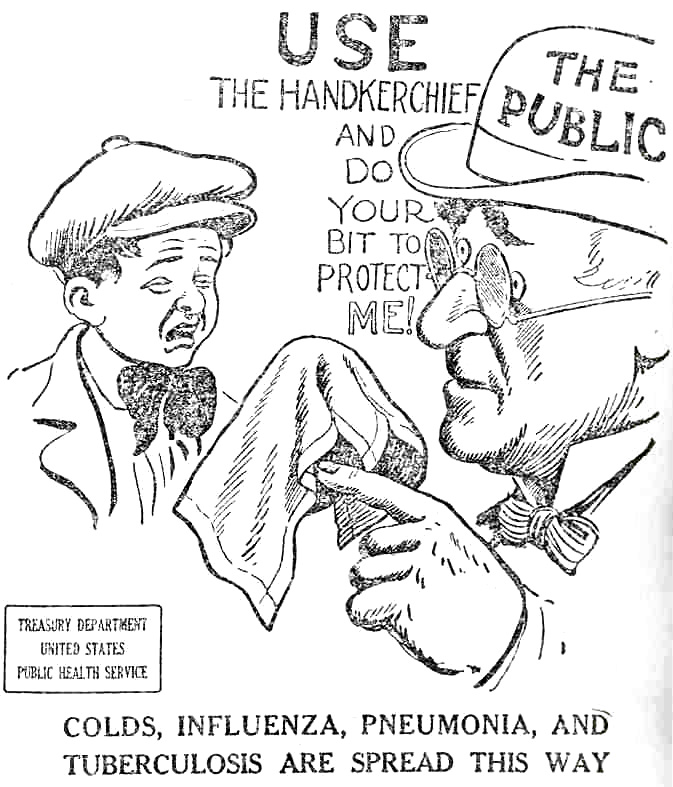

Non-pharmaceutical strategies, on the other hand, are always available and include measures such as closing schools, canceling public gatherings, quarantines, etc. Such measures are also called “social distancing” measures, because if we cannot prevent or treat infections pharmaceutically, at least we can make it harder for the virus to jump from human to human by decreasing the frequency of human-to-human contact.

While social-distancing measures are usually centrally managed by public health authorities, each of us might be developing our own personal strategy to decrease the risk of an infection. This is something most of us do all the time — for example, we instinctively turn away from rotten food or bodily fluids (in particular those of other people). But as the awareness of the threat of a disease grows, we are increasingly alert and might change our behavior accordingly. Awareness comes with news, and the speed at which news spreads these days is orders-of-magnitude faster than the speed at which an epidemic can spread. Once we are confronted with the flow of information pouring in, we react emotionally and behaviorally in our own personal ways.

You can get some idea about the multitude of information and reactions to the current swine flu epidemic by looking at real-time results of a Twitter search — in the past half hour since I hit the search button, 3,699 tweets about swine flu have been sent through cyberspace, including:

all this ‘Swine Flu’ stuff is scaring me. ):

WHO raised swine flu alert to 5! Pandemic!

thinking about this swine flu…im happy i dont eat pork! 🙂

Just read that 36,000 ppl in US die from ‘regular’ flu each year. 13,000 have died since Jan. in US alone. Stay informed, with your TV off.

people, what’s up with this SWINE FLU (gripe suina)??? are you kinda… scared? some of my students are going nuts, freaking out!

Clearly, people are aware of the swine flu, but they perceive the threat very differently and react very differently. How awareness and the consequent behavioral change affects the spread of an epidemic is a topic of intense research — just this past week, my colleague Sebastian Funk at the Royal Holloway University of London published the results of a mathematical model that demonstrates how awareness can alter the progression of an epidemic.

What we need now are good data on the level of awareness, on how people perceive the threat of a pandemic and on how they will react to it. Such data are rare and generally collected only after an epidemic has passed. This is problematic because what we are currently experiencing and what we will remember in the future to have experienced now can be vastly different. The goal of our survey is to gather such data as the epidemic unfolds — that is, right now.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.