In 1996 the Hoover Institution published a symposium titled “Can Government Save the Family?“ A who’s-who list of culture warriors—including Dan Quayle, James Dobson, John Engler, John Ashcroft, and David Blankenhorn—were asked, “What can government do, if anything, to make sure that the overwhelming majority of American children grow up with a mother and father?”

There wasn’t much disagreement on the panel. Their suggestions were (1) end welfare payments for single mothers, (2) stop no-fault divorce, (3) remove tax penalties for marriage, and (4) fix “the culture.” From this list their only victory was ending welfare as we knew it, which increased the suffering of single mothers and their children but didn’t affect the trajectory of marriage and single motherhood.

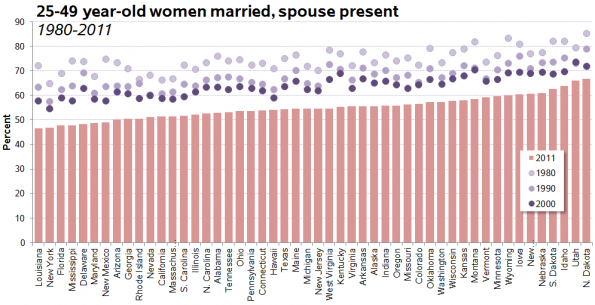

So the collapse of marriage continues apace. Since 1980, for every state in every decade, the percentage of women who are married has fallen(except Utah in the 1990s):

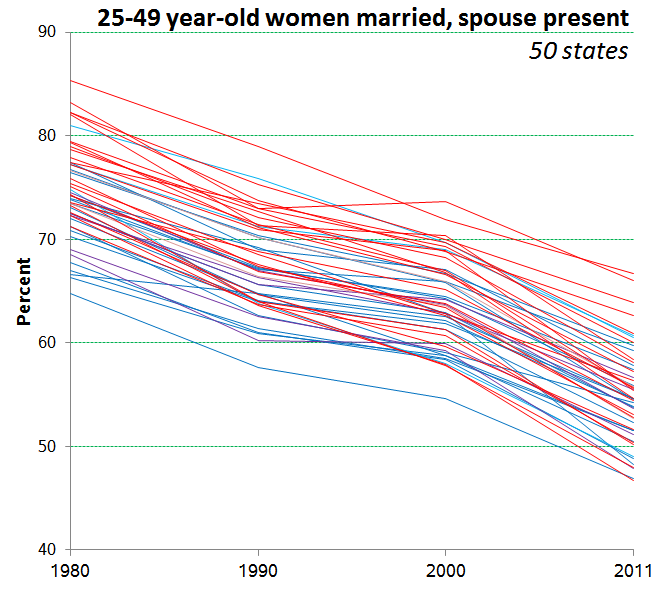

Red states (last four presidential elections Republican) to blue (last four Democrat), and in between (light blue, purple, light red), makes no difference:

But the “marriage movement” lives on. In fact, their message has changed remarkably little. In that 1996 symposium, Dan Quayle wrote:

We also desperately need help from non-government institutions like the media and the entertainment community. They have a tremendous influence on our culture and they should join in when it comes to strengthening families.

Sixteen years later, in the 2012 “State of Our Unions” report, the National Marriage Project included a 10-point list of familiar demands, including this point #8:

Our nation’s leaders, including the president, must engage Hollywood in a conversation about popular culture ideas about marriage and family formation, including constructive critiques and positive ideas for changes in media depictions of marriage and fatherhood.

So little reflection on such a bad track record—it’s enough to make you think that increasing marriage isn’t the main goal of the movement.

PLAN FOR THE FUTURE

So what is the future of marriage? Advocates like to talk about turning it around, bringing back a “marriage culture.” But is there a precedent for this, or a reason to expect it to happen? Not that I can see. In fact, the decline of marriage is nearly universal. A check of United Nations statistics on marriage trends shows that 87 percent of the world’s population lives in countries with marriage rates that have fallen since the 1980s.

Here is the trend in the marriage rate since 1940, with some possible scenarios to 2040 (source: 1940-1960; 1970-2011):

Notice the decline has actually accelerated since 1990. Something has to give. The marriage movement folks say they want a rebound. With even the most optimistic twist imaginable (and a Kanye wedding), could it get back to 2000 levels by 2040? That would make headlines, but the institution would still be less popular than it was during that dire 1996 symposium.

If we just keep going on the same path (the red line), marriage will hit zero at around 2042. Some trends are easy to predict by extrapolation (like next year’s decline in the name Mary), but major demographic trends usually don’t just smash into zero or 100 percent, so I don’t expect that.

The more realistic future is some kind of taper. We know, for example, that decline of marriage has slowed considerably for college graduates, so they’re helping keep it alive—but that’s still only 35 percent of women in their 30s, not enough to turn the whole ship around.

SO LIVE WITH IT

So rather than try to redirect the ship of marriage, we have to do what we already know we have to do: reduce the disadvantages accruing to those who aren’t married—or whose parents aren’t married. If we take the longer view we know this is the right approach: In the past two centuries we’ve largely replaced such family functions as food production, health care, education, and elder care with a combination of state and market interventions. As a result—even though the results are, to put it mildly, uneven—our collective well-being has improved rather than diminished, even though families have lost much of their hold on modern life.

If the new book by sociologist Kathryn Edin and Timothy Nelson is to be believed, there is good news for the floundering marriage movement in this approach: Policies to improve the security of poor people and their children also tend to improve the stability of their relationships. In other words, supporting single people supports marriage.

To any clear-eyed observer it’s obvious that we can’t count on marriage anymore—we can’t build our social welfare system around the assumption that everyone does or should get married if they or their children want to be cared for. That’s what it means when pensions are based on spouse’s earnings, employers don’t provide sick leave or family leave, and when high-quality preschool is unaffordable for most people. So let marriage be truly voluntary, and maybe more people will even end up married. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

This post originally appeared onSociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site.