The story of Philadelphia rapper Meek Mill’s latest prison sentence isn’t over yet. And its new developments are haunted by the specter of an ugly history.

In early November, Meek Mill was sentenced to two to four years of prison for violations of probation. The violations included leaving the Philadelphia area to perform without permission and misdemeanor assault charges resulting from a scuffle with an excitable fan at an airport (those charges were later dropped). The sentencing—delivered against the recommendations of his probation officer—stirred outcry among fans and activists enraged at what looked like a depressingly well-worn story: a talented, young person of color drawn back into a criminal justice system that disproportionately punishes black Americans. Meek Mill’s case is “just one example of how our criminal justice system entraps and harasses hundreds of thousands of black people every day,” rapper and businessman Jay-Z wrote in the New York Times in mid-November.

However, a new development in the story indicates that Meek Mill’s courtroom woes may have as much to do with music-industry scheming as systematic criminal justice inequalities in the United States. A week after Meek Mill was sentenced, Page Six reported that the Federal Bureau of Investigation is investigating the judge in the case, Genece Brinkley, to determine whether she attempted to use her judicial authority to influence business decisions in Meek Mill’s music career. According to a Page Six source, FBI agents have been “in the courtroom” for Meek Mill’s hearings since early 2016, looking into the possibility of an “extortionate demand” made of him by Brinkley. As is their standard practice, the FBI refused to confirm or deny the existence of an ongoing investigation.

Meek Mill’s attorney, Joe Tacopina, who is appealing the sentencing, has previously argued that Brinkley exhibited “enormous bias” in her handling of Meek’s case. Tacopina said that Brinkley has repeatedly suggested that the rapper drop his management team and sign with Philadelphia entertainment mogul Charlie Mack. A source told Page Six that Mack once told Meek Mill that he “knows the judge and he could help him with his case.” Brinkley also reportedly suggested that Meek Mill re-record Boyz II Men’s 1994 hit “On Bended Knee,” and give her a shoutout on the track.

Such an investigation, if it is indeed ongoing, stands in sharp contrast to the FBI’s long history of surveilling and harassing black musicians. These practices spanned decades, genres, and administrative concerns—from fears of communism to gang hysteria—all of which allowed the FBI to amass significant amounts of information on prominent black musicians. Pacific Standard compiled some notable (and egregious) examples below.

The FBI’s focus on black musicians has its roots in the agency’s Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO), which led to the surveillance of several of the most important black jazz musicians of the mid-20th century. FBI documents describe the operation, which officially ran from the 1950s until the early 1970s, as seeking to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” subversive political groups. Though the program targeted many different progressive movements, including anti-Vietnam War groups and feminist organizers, it spent most of its energy attempting to suppress black civil rights groups and prominent black figures with connections to civil rights groups, however small. COINTELPRO infamously sent Martin Luther King Jr. a letter in 1964 encouraging him to commit suicide.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

In 1957, FBI agent Mark Felt (better known as the shadowy Watergate informant “Deep Throat”) wrote to J. Edgar Hoover that a trusted informant had warned Felt of “his most pressing problem at the moment”: Nat King Cole. Cole was a beloved jazz pianist and massively popular singer who recorded over 150 charting singles before his early death. He was not known for his radical politics, and had performed at the Republican National Convention the year before in support of President Dwight Eisenhower. Still, FBI records show that agents repeatedly attempted to determine if he was a communist sympathizer, civil rights activist, or some other kind of troublemaker. Felt’s informant in 1957 was distressed that two hotels in Las Vegas were breaking with the tradition of a segregated Strip and allowing black guests for the duration of Cole’s string of performances at the Sands Hotel. Felt promised Hoover that Vegas would be monitored for the remainder of Cole’s presence.

Other mid-century black jazz greats received extensive FBI attention for anodyne associations with black political organizations. Duke Ellington, the legendary uptown bandleader and jazz pianist, earned a FBI file early in his career for endorsing at the All-Harlem Youth Conference in 1938, which the FBI called “a Communist front.” (The conference was a progressive conference focused on unemployment that received support from Eleanor Roosevelt.) Despite several very public denunciations of communism, including his article “No Red Songs for Me” in the anti-communist magazine New Leader, Ellington was monitored by the FBI for nearly four decades, until shortly before his death.

In 1965, decorated bebop drummer and composer Max Roach received a late-night visit from two FBI agents at home. The agents interrogated him about black nationalist groups he didn’t belong to, later interviewed many of his acquaintances, and kept a file on him for the next decade. The multi-instrumentalist Charles Mingus was also tracked by the FBI for attending an event held by a group dedicated to fighting racism and the Vietnam War, among other matters. Upon seeing a copy of her husband’s file, Sue Mingus called the surveillance “insidious” and “frightening.”

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

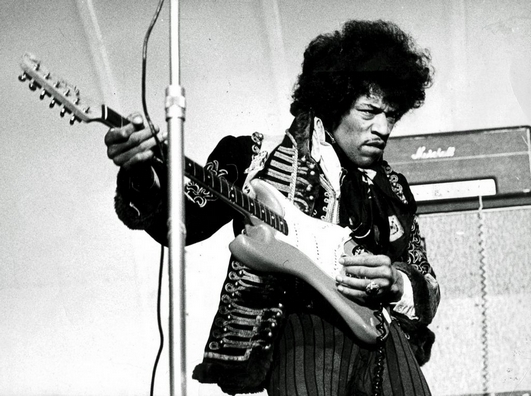

In 1969, the most prominent black musician of the new American counterculture, Jimi Hendrix, caught the FBI’s eye after he was charged with drug possession on a visit to Canada. Despite the radical interpretations of his distorted rendition of “the Star Spangled Banner,” Hendrix regularly expressed hawkish views in support of the Vietnam War and publicly criticized the Black Power movement, once rebuffing the Black Panthers, who were seeking a partnership with him, by telling them “the only colors I see are in my music.” Still, as a racially integrated band playing sex- and drug-infused tunes, the Jimi Hendrix Experience offended many white Americans—the band was threatened with violence and refused hotel rooms in the Southern U.S. on multiple occasions.

While Hendrix was in Toronto for a performance, he was arrested when heroin and hashish were allegedly found in his luggage. (Hendrix’s bandmates later claimed they were warned of the bust ahead of time, and stated their belief that the drugs were planted.) The FBI provided the Canadian government with a folder of past arrests and other incriminating information about Hendrix; nevertheless, he was later acquitted of all charges.

Judging by their surveillance records, the FBI and other policing organizations have repeatedly seen hip-hop and its practitioners as possible threats, from the genre’s earliest progenitors onward. A FOIA request fulfilled this year revealed that the FBI had amassed a 28-page surveillance file on R&B poet Gill Scott-Heron from the 1970s and ’80s, which identifies his speaking at an event held by the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party, a socialist group, as an “extremist matter.” Bridging the musical gap between the earlier jazz cat-targets and the so-called “gangster rappers” on which the FBI would later focus, Scott-Heron often paired explicitly political and Afrocentric spoken word poems with melodies on his his soul-jazz keyboard playing.

A few years later, in 1989, Milt Ahlerich, assistant director of the FBI office of public affairs, sent a strongly worded letter of reproof to Priority Records, rap group N.W.A.’s record label, in response to their 1988 song “Fuck tha Police,” which attacked police brutality. “Advocating violence and assault is wrong, and we in the law enforcement community take exception to such action,” Alterich wrote. Despite admitting in the letter that he had not listened to the entire song, Ahlerich says his reproach “reflect[s] the opinion of the entire law enforcement community.” Though the letter was more censure than censorship, the American Civil Liberties Union, many in the music industry, and the head of the congressional subcommittee tasked with monitoring the FBI all denounced the letter and its use of agency authority to criticize a popular piece of black music.

The FBI has surveilled and investigated many rappers since, including Tupac, Eazy-E, and the Notorious B.I.G. One notable—and extensive—rap related surveillance operation was the FBI’s investigation of the hip-hop collective Wu-Tang Clan, a hip-hop collective. According to FBI files obtained by a FOIA request in 2012, the Wu-Tang Clan has a 281F classification, meaning the FBI sees it as a “major criminal organization.” In 1999, a FBI agent requested permission to travel to a field office in Allentown, Pennsylvania, to learn about “the Bloods street gang” in order to compare their operations to those of the Wu-Tang Clan. The file notes that the FBI was contacted by the New York Police Department, requesting that the FBI pursue a federal conspiracy prosecution against the Wu-Tang “organization” for purported drug-trafficking and execution. No such federal criminal charges ever emerged.

The FBI has continued its war on hip-hop in the current decade. When the FBI National Gang Intelligence Center released their 2011 National Gang Threat Assessment, the report claimed a causal relationship between “gangster rap culture” and an increase in gang membership, and warned of the prevalence of “Gangster Rap gangs” in many states. The report also classified Juggalos (fans of Insane Clown Posse) as a “Caucasian gang,” a designation that Juggalos say caused some to lose jobs, be blocked from the military, and receive stricter terms of probation—suggesting that the FBI’s treatment of music could have discriminatory effects.

To date, that treatment has significantly impacted black musicians and their fans. So while it’s heartening that an FBI investigation might be coming to Meek Mill’s rescue, the FBI’s racist track record should give anyone pause before counting on them as an agency of accountability serving musicians coming from marginalized populations.