Jana Florczak leads the way across a long, quiet corridor with dull grey walls and jimmies open the heavy lock of a giant door. A few steps later, she opens another lock, and enters a storage room. It’s dark and dank, as subterranean, temperature-controlled storage rooms tend to be. But when the light is turned on, relics from the Soviet-era past of former East Germany are revealed: a blue sack here, a brown bag there, another bag over there, all filled with torn pieces of documents left behind by the Stasi—the secret police of the former German Democratic Republic.

Florczak, the chief archivist of these materials, unravels a thick piece of twine binding one of the sacks, and throws the blue bag open. “Too many tiny pieces,” she says, lifting a bunch and letting them slip through the gaps of her fingers like sand. Lifting one such piece from the bag, she shakes her head: “Cannot be used. Look, as small as a fingernail.”

To make sure the enormity of her project is not lost on me, Florczak adds: “Ten storage rooms like this. Full of bags. In this office alone.”

This building in Frankfurt (Oder), a town with red-brick Gothic buildings on the Polish border, had been occupied by the GDR army for about 40 years in the latter half of the 20th century. It is now the Stasi Records Agency—an upper-level federal agency of Germany that preserves the archives and researches the Stasi’s work. Today, 12 such offices exist across the 16 district towns that had been ruled under the GDR regime.

Florczak proceeds to a shelf and reaches for a thermometer. “We need to maintain the temperature so the room remains cool. If moisture gets in, everything will be destroyed,” she says. She opens another bag and peers into it. “This should work.”

Her boss, regional chief Ruediger Sielaff, who accompanies her, leans over. “As long as the paper has been torn only up to three times, we can use it,” he says, signaling that the blue bag is now ready to make its way out. The reconstruction of these schnipsel, or scraps of paper, is now, Sielaff says, “open.”

After World War II, a battered Germany was cleaved apart, and became a rake-off between the Allied forces. West Germany, or the Federal Republic of Germany, was established in the three Allied zones of occupation held by France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. East Germany came to be controlled under the Eastern Bloc, a pro-Soviet Union State. It was here, in 1950, that the Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, or Ministry of State Security, popularly known as the Stasi, came into being. Conflating the dual roles of secret police and secret service, the Stasi surveyed the populace to weed out “counter-state activities” and kept Western influences, such as media, music, cinema, and others, at bay.

In the 40 years that they monitored East Germany, the Stasi ran an apparatus with as many as 91,015 full-time employees and 190,000 “unofficial collaborators”—in other words, informers—to ferret around the GDR population of about 17 million people. Spies and informers were everywhere: at school, on the street, in neighborhood shops, even at home: Some scholars have estimated that, at one time, there was an informer for every seven East German citizens.

(Photo: Sukhada Tatke)

The furtive Stasi infiltrated not only physical spaces but also terrorized people’s interior lives. The organization tapped telephones, opened mail, and bugged homes. Family members told on each other, friends turned into moles, and spies were spied on. The Stasi even captured people’s body odor in bottles and devised ingenious listening and viewing gadgets; they hid cameras in the unlikeliest of places, like in ziplocks and ties. The inevitable recalcitrance from citizens that followed had severe consequences: Thousands of dissenters of the GDR regime were jailed, persecuted, and killed.

Despite their technical prowess, the Stasi’s modus operandi of dealing with its constant influx of information was simple and tedious: Everything was meticulously recorded on paper, filed, and stored away in cupboards.

When the Stasi was dissolved in 1990, protesters surrounded the Stasi offices and demanded access to its archives. Hemmed in, the Stasi staff started destroying its vast network of documentation; they burned paper, pulped it, and shredded it until their shredders became ineffective. With little time left to completely obliterate evidence of their panopticon methods, employees started tearing pages by hand and putting them in bags to be burned later. The plan was never realized: In Frankfurt, Erfut, and Berlin, citizen activists occupied local and regional Stasi offices to prevent the destruction of files.

The Stasi Records Agency was founded in the early 1990s, when it began the gargantuan task of piecing together the torn pages, a jigsaw puzzle so large that it could take decades before it is entirely solved, if at all. The numbers provide an entry point into understanding the extent of the Stasi’s infiltration into citizens’ lives: The organization left behind roughly 16,000 bags, each bag containing between 2,500 and 3,500 fragments of torn pages.

So far, 1.5 million pages from 500 bags have been manually reconstructed, indexed, and archived. There are still 400 to 600 million fragments, adding up to 40 to 50 million pages, that remain to be built.

The blue bag has made the journey from storage to the SRA’s reconstruction room, where the torn pages are pieced together. Chunks of paper from the top of the bag have been laid out on a U-shaped surface, crafted by joining several long tables.

On a warm Wednesday morning in June, Elke Kinzel, who retired last year from the agency, finds herself in this familiar space. She has returned to the office to attend the screening of a documentary—called Schnipsel—on the reconstruction of the papers, of which she is the star. Unable to resist the temptation to visit her former workspace, she darts toward the table. A torn page with elegant handwriting catches her eye. She looks over it carefully, and then begins to pick up one scrap after another, surveying it and putting it back. A few attempts later, she grins. She has found the missing piece, which she assiduously sticks to the torn page with sellotape.

(Photo: Sukhada Tatke)

“It’s some information on an unofficial collaborator, with the code name ‘Buffel,'” Sielaff says. (Unofficial collaborators were given code names by the Stasi to protect their identities.) “The document says he was on his way to meet someone he was spying on.”

There is a method to the madness, a method that Kinzel devised. She separates the torn pages into four parts: top left, top right, bottom left, and bottom right. A different section of the table is reserved for the middle scraps. Then, pieces are arranged based on handwriting, typed font, and kind of paper, among other factors.

Kinzel, in 25 years of a career that Sielaff describes as being “the main jigsaw puzzle lady,” has unjumbled 37 bags. Among the first recruits, she started working in May of 1992 and spent 15 to 20 hours a week painstakingly sifting through pages. “Sometimes, I got so engrossed that I forgot to go home,” she says.

Didn’t it ever get boring? “How could one not get engrossed in such kind of work?” she asks. “It is like you have been given fragments of people’s lives and are asked to tell their story in great detail,” Kinzel adds, with the look of a proud parent.

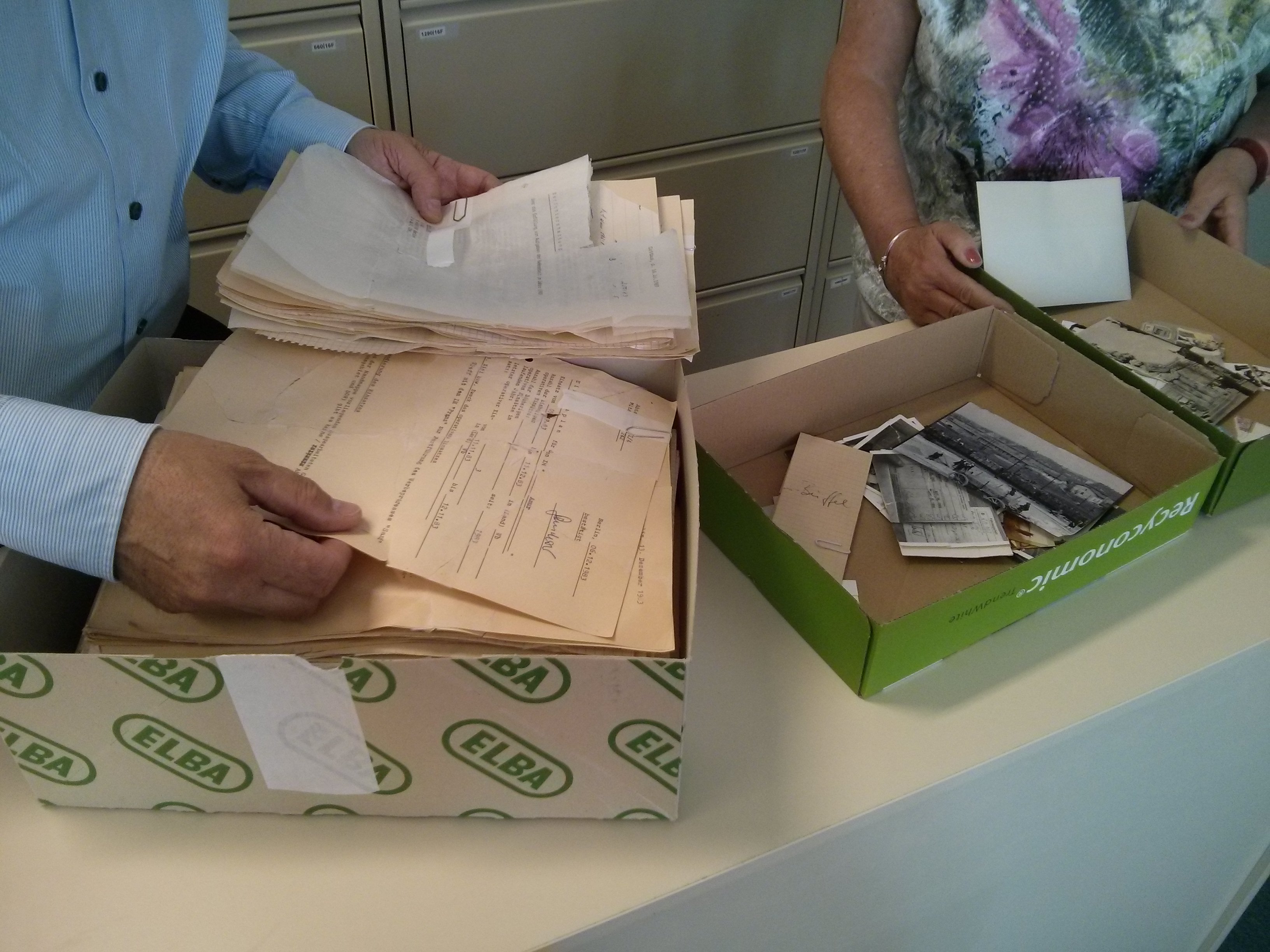

Once the contents of a bag are pieced together in the puzzle room, the product journeys to its final destination before the archives: a room where the assembled pages are filed and organized according to location, the name of the spy involved, and the name of the victim, among other organizing factors. A file on a victim might contain correspondence between the victim and his family, or photographs, or reports on meetings between the victim’s spy and Stasi officials, complete with bills of what they ate and drank at the meeting.

(Photo: Sukhada Tatke)

In this room, Monika Horn is peering into a file and stops at a page where a small portion is missing. “You see? Sometimes, we just don’t find the absent bit, but we have to keep looking. It’s very important that the contents of a particular bag always remain together,” she says. Horn says she spends anywhere between six months and a year on one single bag, working about 15 to 20 hours a week only on filing.

Today, work is on to reconstruct the pages digitally at the SRA’s Berlin headquarters. Since the Agency began using reconstruction software in 2007, fragments from 23 bags have been scanned and virtually reconstructed as a pilot project. However, some documents still have to be reconstructed by hand because the technology is still, at this point, limited.

While each employee has a unique role in piecing together the great puzzle of the past, all are trained to recognize the emergency code, a red circle symbol affixed to shelves of files where the most important documents are stored. Documents pertaining to important institutions, like hospitals, schools, and churches, are housed here; those marked in red are the first to be rescued in case of a fire or flood.

“Did the Stasi have anything on me?” This is the raison d’être of the Stasi agency and archives, the question that it is piecing documents together to answer. On average, 4,500 to 5,000 applications for access to files come in every month. The Stasi Records Act of December 29th, 1991, legally grants Stasi victims access to the documents: Since the Act came into effect 26 years ago, the offices have received as many as 7.12 million applications in total, of which 3.2 million came from citizens, and the rest from historians, researchers, journalists, students, and others.

Lisa Schumann, holding a form in her hand, enters details of one such applicant into a database that scans files across all the offices: name, last name, and address at the time of suspected spying. Nothing pops up on the applicant. Not yet.

(Photo: Sukhada Tatke)

“There is so much that remains to be assembled, that we don’t know when we will find information on this person,” Schumann explains. Even if the SRA finds something on the applicant, it will take anywhere between three to six months to locate that information. “There are 1,800 people in line at the moment in this office alone,” she says.

Under the Stasi Records Act, a person can apply every two years if their earlier attempt has failed to yield results. But if employees find requested information after two years, they are forbidden from contacting the victims on their own. What if they are no longer interested, or want to refrain from possible trauma that the files could cause? Sielaff explains.

This is where the most important philosophical dimension of this mammoth project kicks in. “We have to remember this is not just paper. We are dealing with people’s lives that were trampled upon,” Sielaff says.

Employees are especially reminded of this emotional resonance when characters from the stories they are piecing together emerge in front of their eyes, apparitions from the past.

One day in 2014, Kinzel noticed a pattern. The code name “Thomas” kept cropping up in various files. The informer to whom this code name was assigned, Aleksander Radler, a theologian, spied for more than two decades on hundreds of people; information given by him ran up to 2,600 pages. “When we found his identity, he was a priest in Sweden,” Siefall says.

When the story became public, three people who had been under Radler’s radar visited the archives to read the files. “Seeing those victims take in the extent of betrayal by their friend, that moment was the most emotional in my entire career,” Kinzel says.

By providing a window into a protracted dark moment in Germany’s history, the Stasi archives are, in part, an attempt at contrition; they also seek to prevent similar incursions on German citizens’ privacy in the future.

On this June morning in the Frankfurt Oder office, almost all of the 60-odd employees have gathered for a screening of Schnipsel, the film portraying their work. After the half hour they spend in the dark watching the documentary—at times giggling at seeing themselves on the large screen; watching in awed silence at others—they applaud. When the lights come back on, I ask if they feel they played an important role in retelling a crucial chapter of their national history. Most shrug and smile.

Their boss, Sielaff, breaks the silence: “It is not often that, at the end of a dictatorship, you get to study their files. I hope no other generation has to go through this.”