In the American memory, the Unabomber is more icon than man.

By 1995, the Unabomber had become one of the most notorious criminal figures in America’s recent history, recognizable even from a sketch-artist’s image: white, unshaven, always wearing aviator sunglasses. Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, the Unabomber sent dozens of explosive parcels to advertising executives and college professors, killing three people and maiming half a dozen more.

Since his arrest, the name—alongside the iconic sketch of the man in the hooded sweater—has become an archetype of the unknown and ominous assailant, his identity as mysterious as his pathology. This is our idea of the Unabomber.

Whether the Unabomber could attain such notoriety today is unlikely. In an age of online radical terrorism and no shortage of “lone gunmen,” the Unabomber’s more pedestrian crimes of sending explosive parcels sent across the country via UPS feels almost quaint. Yet the Unabomber lives on in the popular imagination, a figure of enduring national interest, an unbalanced child prodigy grown old and eventually arrested on the cusp of the dot-com revolution, prophesizing to an unconverted mass about the dangers of the Internet age.

Looking back on the Unabomber, what we often forget is that he began as an ordinary suburban man, someone who grew up on the outer bounds of a big American city and who had a fairly unremarkable childhood. He had a mother, father, and brother. He had a pet bird. He had a name: Ted Kaczynski.

These more traditional biographical facts are what drive Every Last Tie: The Story of the Unabomber and His Family, a memoir written by Ted’s younger brother David Kaczynski. The book is an admirable attempt to examine Ted’s early life, offering us glimpses of a more psychological humanity. Most important, David reveals the roots of Ted’s affinity for nature and his increasing alienation from a world that he saw as driven by technological advancement and a digital revolution.

Every Last Tie recounts much of Ted’s earlier life through the lens of his brother’s memories, with a narrative, beginning at home, about Ted’s slow descent into an obsessive warfare with technology, one that saw him retreat to the wilderness and begin his lifelong conquest to spread his manifesto against the dangerous technological age.

David himself acts as an important figure in the Unabomber legend: He was instrumental in leading authorities to Ted after his wife Linda suggested David look at a special insert published by the New York Times and the Washington Post that contained the Unabomber’s manifesto, “Industrial Society and Its Future.” In 1995, David met with agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation and told them about his brother and the likelihood that Ted had written the 30,000-word diatribe, a meeting that more or less led to Ted’s capture in a remote cabin in Montana. Afterwards, David gained national attention for being the man who turned in his brother.

Since Ted’s arrest and incarceration in the late 1990s, David has become passionate about the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism and has been a public and very spirited activist against the death penalty. These spiritual and political commitments provide the backbone to Every Last Tie, as David clarifies the history between him and his brother—emotionally and fraternally—while also engaging the existing biographies of Ted, in hopes of coloring him with some humanity and depth that we don’t generally associate with discourse about the Unabomber. (Notably, the book resists mentioning the term “Unabomber,” except in direct connection with acts of violence or a news item.)

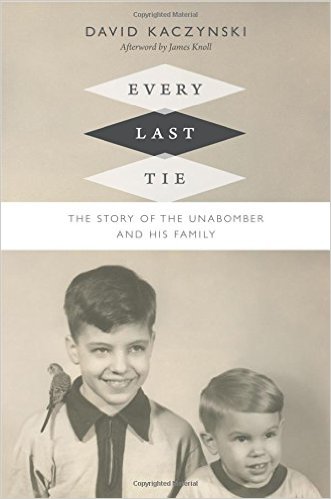

From the outset, we are encouraged to shed the two longstanding images we have of Ted Kaczynski: the infamous “sketch” of a man in a hooded sweater, and the wild, disheveled man posing for his mugshot, the face of a national terror. The publisher’s decision alone to run an image of the Kaczynski brothers on the book’s cover—Ted’s pet bird sitting on the Unabomber’s shoulder—underscores this impulse to humanize Ted. While his crimes were heinous—the exploits of a highly intelligent but deeply troubled individual—Ted had a life before violence, and in order to understand and interrogate his story, we must learn about that early history.

But David has a tendency to over-sentimentalize Ted’s childhood, laboriously recounting stories from their early life about petty childish disputes between brothers and Ted’s wholesome but sometimes strained relationship with parents Wanda and Ted Sr.: Wanda is the caring and protecting mother, determined to see her sons achieve the educational success that both parents missed out on. We learn that Ted is talented in mathematics and, after completing his high school diploma at 15, is accepted at Harvard University, where he soon finds the experience emotionally and psychologically taxing and becomes a lonesome, reclusive adolescent lost in a college world, with the dwindling ability to maintain the level of privacy he had enjoyed at home.

Every Last Tie is thus predicated on themes of kinship and fraternity, a brother’s attempt to make peace with his notoriety for turning in his brother. While the memoir is laced with sentimental insight, David sometimes indulges the tendency to over-analyze Ted, a tendency that often leads to counterintuitive claims. David offers anecdotes from the boys’ childhood, for example—about caring parents and being second-generation immigrants—before telling us about their father, who was a passionate advocate of “civic duty”; indeed, Ted Sr. was so committed to his civic duty that he entered local politics. The implication is clear in David’s telling: The parents instilled a strong sense of civil obedience in their sons, a respect for the nation’s laws. But David does not connect this reminiscence at all with Ted’s future behavior; instead, David lets many anecdotes like this hang unconnected, untied to Ted at all, mere disjointed snippets of a childhood that seems otherwise unremarkable.

Still, many of the recollections are revealingly intimate instances of a precocious but troubled boy. We learn that Ted developed a lifelong obsession with a story his parents told of him—that he was left in hospital in isolation as an infant because of an outbreak of hives. David says that Ted internalized this experience as one of deep abandonment trauma, and was moved therefore to “preempt the inevitable by rejecting family,” moving to an isolated cabin in the woods while sending his raging letters to his parents, writing about how he continued to feel rejected and unwanted.

David excels when he offers more substantial narratives about Ted’s relationship to his parents and the growing distance Ted builds between himself and his family. That distance is told through an epistolary narrative, as David summarizes Ted’s increasingly angry and bitter letters to their parents, offering us an intimate and unvarnished look at Ted’s manic and unbridled emotional states. These “emotional bombs” were incredibly distressing experiences for Ted’s parents. What stories like these offer—so often overlooked in the greater biography of Ted Kaczynski—are small nods to Ted’s inability to form close, familial bonds with others, his close affinity to nature and animals, and his disillusionment from the increasingly technology-dependent modern world.

David valiantly tries to fill in these gaps left by many previous biographies, but still the recollections of Ted rarely feel three-dimensional; more often, we get brief anecdotes and long, verbose psychological analyses. David himself also proves a curious case study, eventually acting as a kind of foil for his brother. Like Ted, David spent years in isolation, living in the “Texas desert,” as he puts it. David had a lifelong obsession with a girl called Linda he met in elementary school, and after she did not reciprocate his advances during high school and college, David left mainstream society—a move Ted similarly made at 29 to a cabin in Montana—where he spoke Linda’s name under his breath “daily.” One wonders whether David’s own confessional stories—sometimes more self-incriminating than actually endearing—are shared in hope that readers will view his biography of Ted with deeper sympathy.

David actually sought a substitute for Ted in the years since Ted’s incarceration, befriending a man named Gary Wright, a computer storeowner in Salt Lake City who survived one of Ted’s bombs but endured severe nerve damage to one of his arms as a result. This fraternal bond felt like a “poetic balance,” as David reached out to the victims, and the victims reconciling their deep anger and frustration. Since their meeting some decades earlier, David and Gary have formed an intense bond, one that David discusses in brotherly terms. (He also notes he has not spoken to Ted in more than 15 years.) Every Last Tie is certainly preoccupied with issues of brotherhood and family ties, seeking to examine and humanize one of the most notorious figures of recent memory through a brotherly bond.