I first learned about America’s most famous marriage evangelists, Harville Hendrix and his wife, Helen LaKelly Hunt, because a friend of mine told me about an instructional video she’d seen online that taught a reconciliation technique known as Imago dialogue. I had 11 weddings to go to that summer and was spending many evenings listening to friends talk about their pre-marital counseling plans, which ranged from rigorous to makeshift. Imago, I learned, is a formalized conversation that Hendrix and Hunt have devised to defuse conflict between couples. It involves repeating and verifying what the other person says. The listener is supposed to keep asking, “Did I get that right?”

Imago dialogue might seem like a straightforward solution to conflict, but, I soon realized, Hendrix and Hunt conceive of it as part of a larger effort. They want to use Imago to prevent divorce—first in America, and then, presumably, everywhere.

“We’ve each been divorced, and we think it’s wrong,” Hunt told me the first time we met, at a restaurant near their apartment on the Upper West Side. Hunt has a gentle smile, a high-frequency energy, and a Texan twang to her speech.

Hendrix joined in. “If you could end divorce,” he said, “you can save American families and the American economy.”

Imago effectively rules out mismatches. You’re with the right person if you are happy, and you’re with the right person if you’re miserable and fighting.

They speak proudly of their differences and believe it can be scientifically proven that opposites attract. Hendrix, 79, comes from poverty. His parents died before he turned six, and he was raised by siblings on a small farm in southern Georgia. Hunt, 66, comes from money. She is a daughter of billionaire oil tycoon H.L. Hunt, one of the inspirations for the television series Dallas. Hendrix is studious, Hunt is expressive; he’s the thinker, she’s the doer; he’s calm, while she always needs to be busy. Hendrix warned me that his wife would probably sit down with me for only 20 minutes at a time. Sure enough, exactly 20 minutes after she arrived, she excused herself. He stayed on for almost two hours.

Studying marriage with the person you’re married to might be the surest way to never get a day off. Hunt and Hendrix have published 11 books, including the bestseller Getting the Love You Want. Oprah Winfrey refers to Hendrix as the Marriage Whisperer, and she had him on her show 12 times. Hendrix and Hunt never stop speaking in Imago dialogue. Hunt repeated my interview questions back to me: “You want to know why we think our work resonates with people. Did I get that right?” They told me they were trying to add more fun to their marriage and had started to watch Stephen Colbert and David Letterman. They talked about laughter the way other people talk about vitamins.

In 2008, Hendrix closed his private couples-therapy practice in Manhattan, and he and Hunt started two new projects. The first was the launch of a think tank, Relationships First, which aims to strengthen couples. (They were excited to have Alanis Morisette and her husband, the rapper Souleye, as board members.) The second was to launch their move- ment to promote coupledom and end divorce. The starting point would be Dallas, a city they saw as big enough to make a meaningful impact but small enough that they could track their progress. Dallas also has sentimental value: It’s where Hendrix and Hunt met. Hendrix’s hope is that the city’s measures of well-being will climb as the movement catches on.

Most adherents of Imago therapy are paying clients, the sort who drive Audis and make last-minute plans to see Gilbert and Sullivan operettas, but Hendrix and Hunt want to bring Imago to people of all backgrounds. They believe there’s no one they can’t help: rich or poor, religious or non-religious, young or old, gay or straight. “We’ve had a 300-year focus on individuals, and that period and paradigm has run out of value,” Hendrix told me. “There’s an emergence into the collective happening right now, a critique of individualism, capitalism, and self-centered living.” People, all people, want and need Imago.

In April 2014, a few months after meeting Hendrix and Hunt in Manhattan, I traveled down to Dallas, where they were hosting their fourth workshop, called Safe Conversations. The location was a windowless conference room in the Momentous Institute, a children’s non-profit in southwest Dallas.

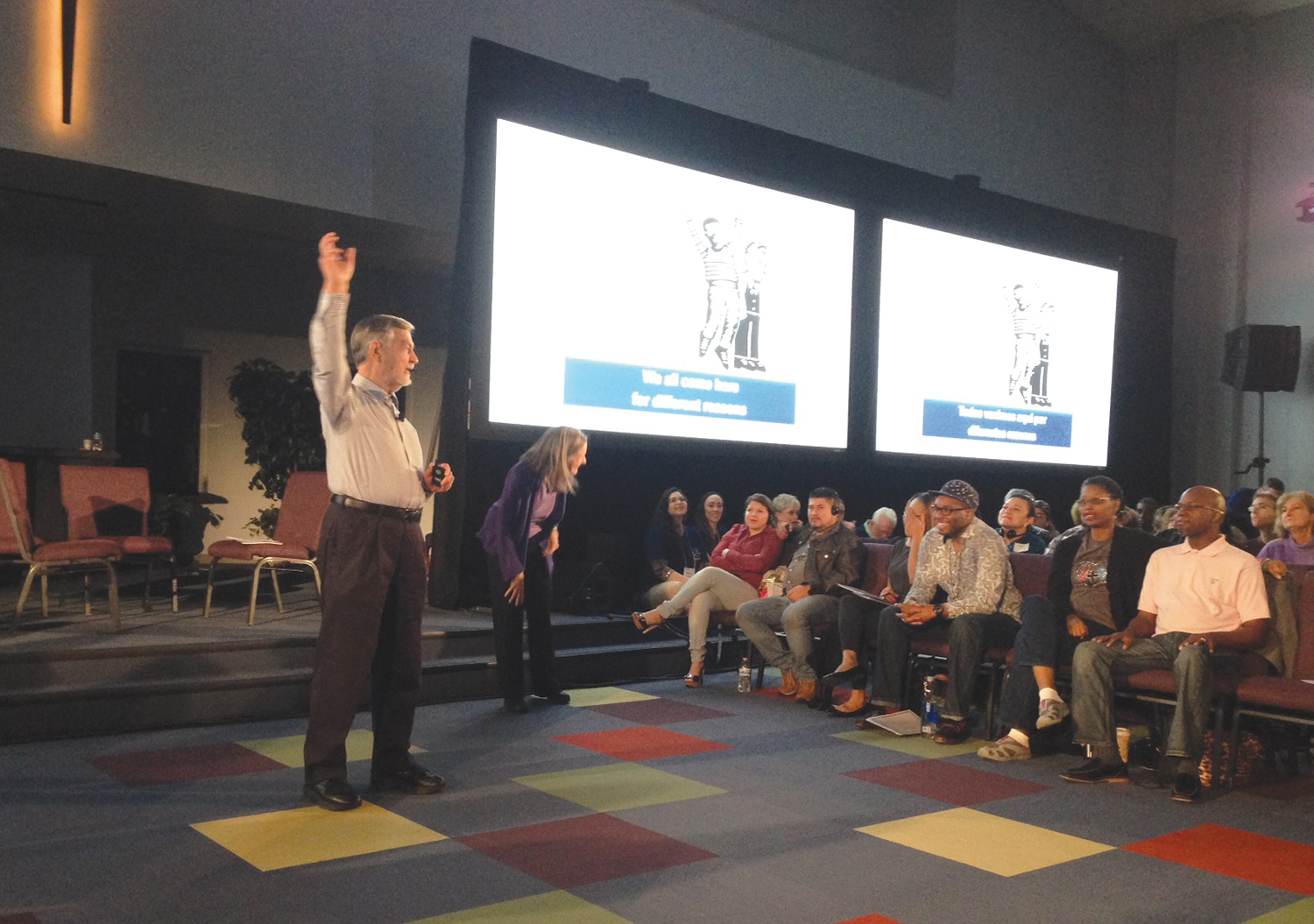

Two hundred and twenty people were in the audience, about half of them Hispanic (there was live Spanish translation available) and the rest divided evenly between black and white. Most lived in the surrounding neighborhood, Oak Cliff, a largely working-class, Hispanic area. Volunteers in turquoise T-shirts roamed the room handing out snacks and passing the microphone to people, and 22 clinical volunteers in navy T-shirts patrolled the workshop for couples in distress.

Onstage, Hendrix was trying to get a young couple to engage in a dialogue sequence. The pair sat in armchairs facing each other, and Hendrix told the man, Michael, to pay his wife of three months, Tara, a compliment.

“What I appreciate most about you is that you’re a good cook,” Michael said.

“So what I’m hearing you saying is that you appreciate that I’m a good cook,” Tara said. She seemed bored.

To prompt Michael, Hendrix began, “When I think about you as a good cook, I feel—”

“When I think about you as a good cook,” Michael said, “I feel full, sleepy, and—sexy.”

“Really?” asked Tara, a little annoyed. The woman sitting next to me groaned.

Hendrix jumped in: “When I think about you as a good cook, it reminds me of—try to find something from your childhood.”

“When I think about you as a good cook, I—” Michael stopped, then started over. “When the house smells good, it reminds me of home and when my mom cooked and I felt loved.”

Tara repeated him, her eyes now glassy with affection. Unprompted, she spoke the next line in the sequence: “Is there anything more about that?” There wasn’t. They hugged for 60 seconds as the rest of us watched. Hendrix told the crowd that the length of an average hug is three to nine seconds, but that a good hug, one that “pushes the boundaries of relationship,” takes a whole minute.

Hendrix has a trove of mysteriously sourced facts like this. Most of them, he says, are the product of investigation conducted either by him or by fellow Imago counselors, of whom there are more than 1,000 across the globe. Hendrix, who has a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago Divinity School, started to study relationships in the late 1970s, shortly after his own divorce, and his ideas are inspired by texts ranging from Freud to the New Testament. “There’s a dyadic structure of nature,” he explained. “Whenever a particle comes out of a void and into space, it comes with another particle.”

For all the grand theories of love, the workshop emphasized actions. During a segment dedicated to “high-energy fun,” Hendrix and Hunt jumped up and down synchronously, breathing heavily, until they burst into laughter. Regular belly laughs, they say, are key to a happy marriage.

As the day went on, people around me were conducting exercises and being driven to tears, revelations, and reconciliations. I talked to Darrel and Kayla Young, who had been married for 10 years. They had been to the previous Dallas workshops and hoped to attend more. They’ve become such adherents of Imago that they plan to launch a petition to require a pre-marital course and exam for anyone in Dallas who wants a marriage license. “You gotta take a test before you get your hunting license or your fishing license,” Kayla said. “Marriage is harder than fishing.”

Hendrix and Hunt cater mainly to people who are married, but all varieties of couples are encouraged to come to the workshops. One couple in Dallas was a pair of sisters who sprinted through every exercise and jumped up to give each other long hugs. Down the hall, where free daycare was being offered, children of parents in the workshops were likewise learning Imago dialogue, and I stopped in to watch. “What I’m hearing you saying is my bike was in the driveway and you hurt your leg,” one second-grader told another kid. “Did I get that right?”

Like so many institutions of American life, marriage gets drawn into the culture wars. Many politicians, especially conservatives, have promoted marriage as an antidote to social decline and welfare expansion or, as Senator Marco Rubio recently put it, as “the greatest tool to lift children and families from poverty.” On the other side are those who argue that marriage is a benefit, not a generator, of wealth—an interpretation that is common among social scientists. “Having a good relationship is not about knowledge and it’s not about skill. It’s about having resources,” argues University of California-Los Angeles psychologist Benjamin Karney, laying out the latter view. “You have to improve the community in which that marriage is and the lives of the people in the relationship.”

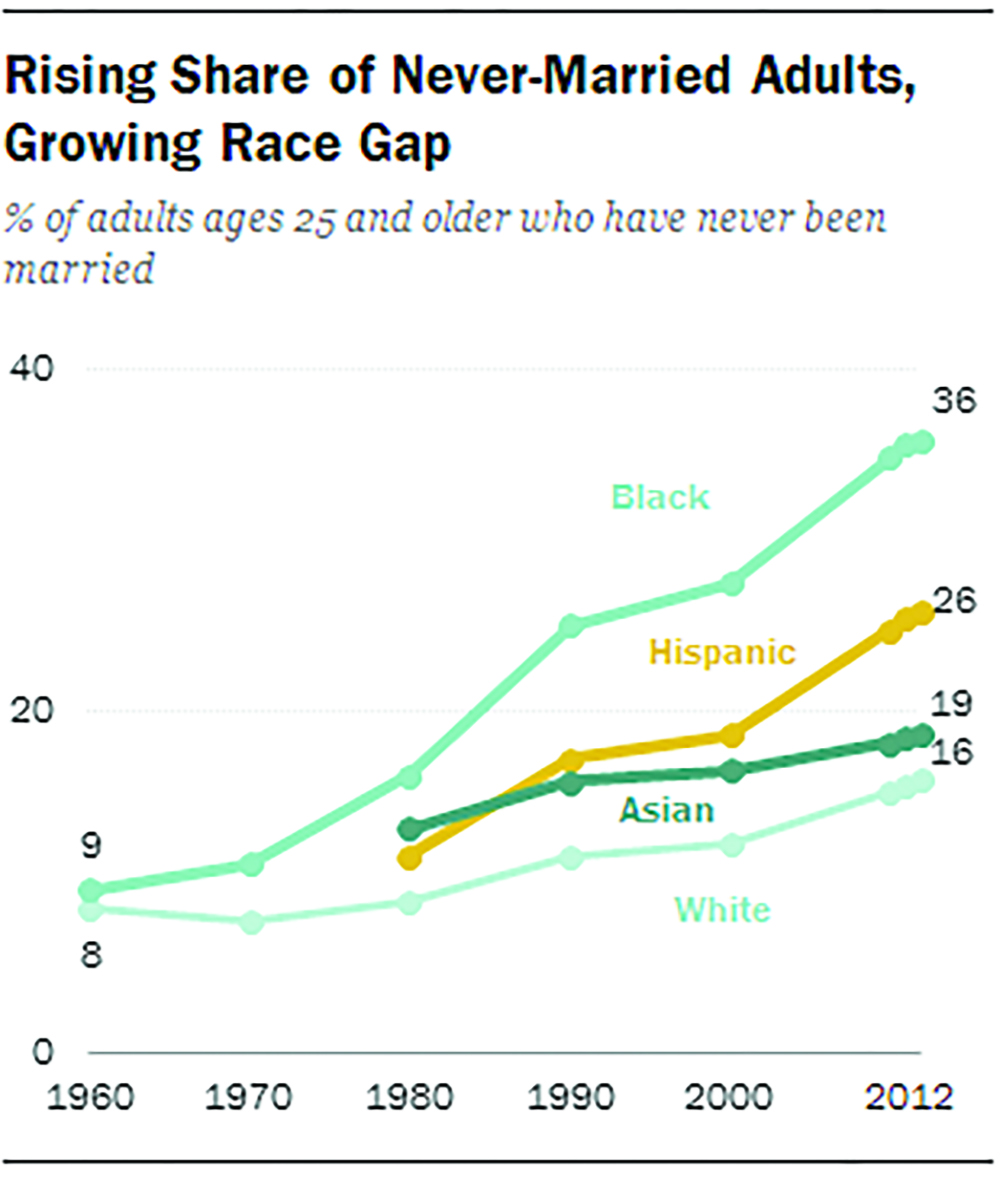

What everyone agrees on is this: The rate of marriage in the United States, while in slow decline, remains higher than that of Japan, Germany, or Canada. For the past three decades, the rate of divorce has also been in decline. At the same time, poor Americans are getting married at much lower rates than wealthy Americans, and their rates of divorce are much higher. This is one reason that Hendrix and Hunt offered their Dallas workshops, which would normally run about $500 a head, for free, even putting up their own money. They hope the lessons will help couples who could not normally afford them.

Hunt and Hendrix have spent most of their marriage and careers on the Upper West Side, and they contribute to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. Hunt, who was inducted into the Women’s Hall of Fame for her philanthropic work, counts the feminist Gloria Steinem among her closest friends. When they enter the marriage debate, however, they hope to avoid partisanship. Economic statistics are not their main concern. Rather, they believe being in a couple is natural and being single is not. “As individuals, we each have emotional wounds that need healing,” Hendrix and Hunt write in one of their workbooks, “and on some level, we know that it is only in the context of a committed relationship that this healing can occur.”

One of their favorite examples is their own. Hendrix and Hunt first met in 1977. He was teaching psychology at Southern Methodist University, where she was completing a master’s degree in counseling. They met at a party and discovered they shared an interest in Martin Buber and Dostoevsky. Each also had two children from a previous marriage. They fell in love, and married five years later.

Their trouble started in the mid-1990s. It should have been a joyful time. Getting the Love You Want had become a runaway hit following an appearance by Hendrix, his first, on Oprah. But they were miserable. He would claim to be buried in work and lock the door to his office and watch Star Trek late into the night; she would draw up lists of all the things he was doing wrong, like wearing too many Earth tones and cracking bad jokes at parties. They had become critical of one another, passive-aggressive, and finicky. They tore through marriage therapists; No. 5, they say, called them “the couple from hell.” At a conference for Imago therapists, in 1998, they confessed that they were heading toward divorce.

Poor Americans are getting married at much lower rates than wealthy Americans, and their rates of divorce are much higher. This is one reason that Hendrix and Hunt offered their Dallas seminars, which normally run $500 a head, for free.

To save their marriage, they decided to devote one year to trying to fix it. The first policy was to eliminate all negativity from their interactions. Neither of them was allowed to say anything spiteful. Ever. They taped a calendar to the refrigerator and drew a smiley face when they made it through a day with no negativity and a frowny face when one of them slipped.

Once Hendrix and Hunt had eliminated all the negativity from their relationship, they didn’t have much left to say. “We had a silent love,” Hunt said, laughing. They filled the silence with compliments, belly laughs, and writing about their experiment.

The Zero Negativity Challenge is now a tenet of their relationship philosophy, and has been added to the 20th-anniversary edition of Getting the Love You Want. At workshops, volunteers pass out blue silicone bracelets bearing the letters ZN (for Zero Negativity) and information on how to download a Safe Conversation app for their mobile devices. The app offers a digitized version of the calendar that once hung on Hendrix and Hunt’s refrigerator, reminders to pay your partner a compliment, assistance with Imago dialogue, and a shortcut to the Couples Store, where you can buy their books.

Hunt and Hendrix held hands during one of our interviews. They kissed onstage during the Dallas workshop. They’re very attentive to each other. “Do you need to take a minute?” Hendrix asked Hunt before the workshop. She did. She’s careful to give him time alone to watch Star Trek. Effortless is not a word anyone would use to describe their manner. They show their love through well-practiced and -calibrated interactions.

Scholars have devoted extensive study to individual therapy but surprisingly little to couples therapy. “A dirty little secret in the therapy field is that couples therapy may be the hardest form of therapy, and most therapists aren’t good at it,” wrote William Doherty, the director of the marriage and family therapy project at the University of Minnesota, in an article for Psychotherapy Networker. Even the goal of most couples counseling remains unclear. Virginia Satir, a psychologist who practiced in the 1960s and ’70s and is considered a pioneer of family therapy, has said that her goal with couples was “not to maintain the relationship nor to separate the pair but to help each other to take charge of himself.”

Unlike most conventional marriage therapy, Imago has a clear and simple definition of success: reconciliation. This appeals to many practitioners and clients alike. Sessions are civil and feel productive. But is keeping a couple together always a sound goal? Hunt and Hendrix believe so. According to their findings, we are all instinctually attracted to people who can help us heal from childhood traumas. They argue that it’s impossible to fall out of love, that conflict is a sign that you’re with the right person, and that fighting is essential to emotional and spiritual growth. Mismatches, by this logic, are effectively ruled out. You’re with the right person if you are happy, and you’re with the right person if you’re miserable and fighting.

This has made Hendrix and Hunt into absolutists. “You end the relationship when the person is brain-dead or brain-damaged,” Hendrix says in one video, in response to a question of when to call it quits. “As long as they can talk and relate, there’s hope for a relationship.”

Even cases of spousal violence are resolvable. “It takes two to create this warped ballet,” Hendrix and Hunt write in Keeping the Love You Find. “What is rarely acknowledged is that the battered wife knows only one way—the way she learned from her own mother—to get attention, and that is to provoke her distant, silent husband with relentless, though perhaps subtle, criticism, complaints, and rejection—until he explodes.”

Later in the chapter, Hendrix and Hunt acknowledge that abuse by an unrepentant partner should spell the end of a relationship, but, “when the addict or abuser is willing to acknowledge and work on the problems,” then “the attempt to save the relationship should be made.” I sent Hendrix and Hunt an email asking them to comment on these passages, but they did not respond.

In Dallas, I met Tammy and David, who had been married for 30 years and separated for six months. “I was being abused,” Tammy told me while David was in the bathroom. “He threatened to kill me in front of my kids.” She moved into a women’s shelter, but a divorce group made her decide never to have one. She wanted to stay with David, and had read Hendrix and Hunt’s books. “Separation is painful enough,” Tammy said. “I don’t want to end up repeating the same patterns with someone new.”

As a method of communication, Imago appears to be effective. In Dallas, as I saw the reactions among participants, the desire among couples to reconnect in love, it was hard not be moved. “I felt respected,” a woman in a pale pink T-shirt told the audience, clutching the microphone with one hand and her stomach with the other. “I started crying because I don’t think I’ve ever felt that way before.” Many couples at the workshop told me of their wonder and gratitude toward Hendrix and Hunt for offering free counseling, as well as complimentary daycare and lunch. Having a full day alone with a spouse was normally out of reach. Many left the workshop grinning.

But Imago is also an ideology, one that aims for simplicity and universality. To preserve the notion that Imago is right for every couple, Hendrix and Hunt are loath to make exceptions. “It is the case that every couple is different, as is every leaf on a tree,” Hendrix and Hunt wrote me in an email, “but every couple is also similar in their relational needs.”

Hendrix and Hunt are not allies of red-state conservatives. They reject efforts in states like Louisiana to make divorce more difficult. But their zeal for reconciling couples often takes them to a similar mindset: stay together, no matter what. With Imago, no one, not even an abuser, is too far gone to become a good partner. “We have a mission to heal each other,” Hunt told the crowd in Dallas.

When I got married, plenty of older friends offered the classic warning that marriage takes work, but no one took me aside and explained what the work looked like. “With my mom friends, we talk about taking our kids to the dentist, to speech therapists, to tutors,” said Beth Reeder Johnson, who coordinates the clinical volunteers for the Dallas workshops. “But no one talks about their plan for their marriage or their marriage philosophy.” Marriages are private and, therefore, hard to emulate.

Imago, with its rigid and programmatic rules, is easy to emulate. It offers simple answers, and that is the appeal. It might not be an ideal model, but amid the eternal uncertainties of love and partnership, people are eager to have a model at all.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psmag.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity, and may be published in any medium.

For more from Pacific Standard on the science of society, and to support our work, sign up for our email newsletter and subscribe to our bimonthly magazine, where this piece originally appeared. Digital editions are available in the App Store (iPad) and on Zinio (Android, iPad, PC/MAC, iPhone, and Win8), Amazon, and Google Play (Android).