Editor’s Note (01/20/2014): The primary study upon which this post is based has since been retracted.

The Independentinforms readers that younger married women on Facebook are less likely to take their husbands’ surnames when they wed. From the British paper: “[M]arried women in their 20s are far more likely to have kept their maiden name than women in their 60s. A third of married women in their 20s have kept their maiden name, according to a study by Facebook.”

Some 63 percent of married women in their 20s took their husbands’ names. That figure was 80 percent for married women in their 30s, and 91 percent for married women in their 60s. According to The Independent, this is “a sign that the younger generation is increasingly embracing feminism.”

This might be a little exaggerated. As Jen Doll wrote at TheAtlantic Wire last year, despite the prominence of women who keep their own names among the world’s journalists, actors, and others in the public sphere, most American women who marry opt to change their surnames.

Some 10.1 percent of American college students agreed with the statement that “a woman keeping her name was less committed to her marriage.”

But while some 35 percent of American women in their 20s and 30s are now choosing to keep their own names, that doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with a “resurgence of feminism,” interesting as that would be. While retaining one’s maiden name upon marriage has historically been pretty closely affiliated with feminism, it’s also a sign that, for a lot of women, adult identity is now already established well before getting wed.

The first American woman to publicly insist on retaining her maiden name upon marriage was reportedly the abolitionist and suffragette Lucy Stone, who kept being Stone after her 1855 wedding to social reformer (and Republican Party founder) Henry Browne Blackwell. Today, the Lucy Stone League, which advocates for women’s equality, keeps up the tradition, urging women to retain their own surnames, “because a person’s name is fundamental to his/her existence.”

What’s really going on in America is probably something much more prosaic. Feminism as a defined movement actually appears to be on the decline. Only 38 percent of women in the United States now consider themselves feminists. (In the United Kingdom it’s only 14 percent.) The reason for the name change refusal is likely tied to the fact that, over the last 50 years, the age at the time of the first marriage has increased drastically. Today, the average woman is 27 years old when she first gets married. In 1990, she was 23. In 1960, the average bride was only 20 years old.

The results of this should be unsurprising: Many women already have careers by the time they marry. They have college degrees or law partnerships and published work. It’s time-consuming and difficult for a woman to change all of the documents affiliated with such things and convince people from networks past and present to start calling her something else.

There are important implications for name changes. While some 10.1 percent of American college students agreed with the statement that “a woman keeping her name was less committed to her marriage,” women in higher prestige jobs (medicine, the arts or entertainment) are most likely to keep their names.

Part of this may stem from a desire to avoid having to change it back. The intricacies of this can get rather outlandish for women who have the misfortune of marrying multiple times. One could end up with problems like that of Demi Moore, an actress whose identity constitutes a sort of coral reef of failed marriages. She grew up Demi Guynes, but she achieved fame under another surname. “Moore” is technically the legacy of a marriage that ended in 1985. She was also compelled to change her Twitter handle last year—having somewhat ill-advisedly gone with @mrskutcher—when her third marriage, to actor Ashton Kutcher, collapsed.

Whether or not one retains one’s name is affiliated with all sorts of professional and class implications. In the most extensive look at women’s naming conventions ever conducted, a 2009 study published in Social Behavior & Personality, researchers…

…used data obtained from wedding announcements in the New York Times newspaper from 1971 through 2005 to test 9 hypotheses related to brides’ decisions to change or retain their maiden names upon marriage. A trend was found in brides keeping their surname, and correlates included the bride’s occupation, education, age, and the type of ceremony (religious versus nonsectarian). There was mixed support for the hypothesis that a photograph of the bride alone would signal a lower incidence of name keeping.

The more traditional a marriage appears—young bride, no professional degree, religious ceremony—the more likely Jane Smith will become Jane Doe.

Research shows women are perhaps rather career savvy when keeping their names. In a Dutch study published in 2010, researchers looked into the perceptions people had of women’s competence and intelligence based on their use (or not) of their husbands’ surnames:

A woman who took her partner’s name … was judged as more caring, more dependent, less intelligent, more emotional, less competent, and less ambitious in comparison with a woman who kept her own name. A woman with her own name, on the other hand, was judged as less caring, more independent, more ambitious, more intelligent, and more competent…. A job applicant who took her partner’s name, in comparison with one with her own name, was less likely to be hired for a job and her monthly salary was estimated €361 lower.

That’s $472 a month. Basically, women appear more like successful professionals when they keep their names.

But it’s not necessarily one or the other. There’s also the sort-of name change. As one academic explained earlier this year in New York magazine, “the 5 to 10 percent of women who keep their names — ‘and that includes hyphenators’ — does not account for ‘situational name users,’ those who go by different names in different circumstances.” And, while it’s impossible to verify this, because it’s definitionally unofficial, this appears to be very common.

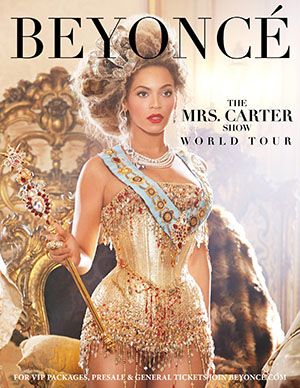

The singer Beyoncé Knowles, for instance, called her world 2013 tour the Mrs. Carter Show (this is odd on a few levels, but mostly because her husband, while born Shawn Carter, is known now as simply Jay-Z). There are a lot of people like her, who use different names in different places. Her name is Beyoncé Knowles, but she’s commonly known as just Beyoncé. She’s legally Beyoncé Knowles-Carter. Maybe her grandmother sends her letters addressed to Mrs. Shawn Carter. There are probably even some people who call her Mrs. Z.

This isn’t to say that women who retain their own names aren’t at some level feminists. The common definition of feminism is the belief that men and women are legally, politically, and socially equal. These women often have jobs where they compete with men, and win, on a regular basis. But they’re mostly not very strident about women’s liberation.

Or they’re not as strident as first-wave feminists, a group whose agenda televangelist Pat Robertson once (bizarrely) characterized as “not about equal rights for women. It is about a socialist, anti-family political movement that encourages women to leave their husbands, kill their children, practice witchcraft, destroy capitalism, and become lesbians.” His statement was an exaggeration, but it reflects a common perception of early feminists as extreme.

Today’s newly married women might be low-level feminists, but more importantly they often come to the altar with careers and their well-established identities and property; their own condos and cars. So, they’ve got husbands now. That doesn’t mean they have to change their whole identities and start calling themselves something else.

As the Social Behavior & Personality study put it:

In the case of women who are business owners, senior level executives, professionals (e.g., physicians, attorneys), and those with careers in the arts and entertainment fields, their names are distinctly associated with the work they have produced, almost akin to a “brand.”

This doesn’t seem to matter in many foreign countries at all. In Hispanic nations this appears to be a non-issue. Women simply retain their own names from birth until death. This has nothing to do with the power of women in society and their ability to vote, hold political office, or own businesses and control property. This is also true, interestingly enough, in most Arabic-speaking countries; women retain their own names upon marriage.

What we’re seeing in America is that the older the bride, and the better her job, the more likely she is to keep her name. In the long run, that’s probably a good idea for her career (that’s $472 a month). This is true even without the killing children, destroying capitalism, and practicing witchcraft hyperbole. It just doesn’t make a lot of sense to take on a new name after putting so much effort into establishing the original one.