By 1977, it was clear that the look and sound of trucking—catalyzed by the rise of civilian CB radio use—had become a genuine craze in America.

That year, only Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind grossed more at the box office than the trucker action-comedy Smokey and the Bandit, which gave Jerry Reed a top 10 hit with his theme song for the movie. A year later, C.W. McCall’s 1975 chart-topping song “Convoy” inspired a film of the same name, starring famous faces like Kris Kristofferson and Ali McGraw.

The films, though, were just following a burgeoning new musical trend that would soon spawn a bona fide subculture. During the 1960s, trucker country had already evolved into its own, under-the-radar genre, with performers like Dave Dudley, Dick Curless, Red Simpson, and Red Sovine helping shape the new sound.

“There were revved-up, twangy guitars, based in hot-rod surf music, and the baritone deep, rumbling voice, echoing the sounds of trucks,” says Jeremy Tepper, the program director for Sirius XM’s Outlaw Country channel and creator of the satellite radio network’s trucker-focused Road Dog channel. Both Simpson and Sovine popularized a half-sung, half-spoken vocal style—a slow recitation that evoked the sound of a conversation on the CB.

It was music made for, and inspired by, the sounds of the road.

The establishment of the interstate highway system in the middle of the 20th century had been a boon for the trucking industry, which was already slowly beginning to outpace rail as America’s primary freight delivery system. Many of those who found work behind the wheel of big rigs came from rural backgrounds, creating a natural link to the also-booming country music business.

Record labels like the Texas-founded, Nashville-based Starday Records, an early home to George Jones, Willie Nelson, and Roger Miller, stocked truck stop jukeboxes with country singles. Soon, songs about trucking itself—like Dave Dudley’s “Six Days on the Road” (1963) and Del Reeves’ “Girl on a Billboard” (1965)—began to emerge. It was a pop music phenomenon that was also deeply rooted in the folk tradition of chronicling workaday life and labor.

“They were rooted in work songs,” says Tepper, a former editor of the Country Music Hall of Fame’s Journal of Country Music. “Cowboy songs, for example, [and] train songs identify closely with the American landscape.”

American workers, real and imagined—from John Henry to Casey Jones—had been commemorated in song for more than 100 years, part of a musical tradition that stretched back even further to sea shanties and broadside ballads. And now, fueled by the charting hits and popular movies, a certain romance had arisen around the image of the American trucker as blue-collar hero. (Indeed, a 1975 work of popular sociology by Jane Stern was lyrically titled, Trucker: A Portrait of the Last American Cowboy.)

• The Environmental Impact of Long-Haul Trucking: Barring some monumental development that disrupts cargo shipping entirely, we’re stuck with trucking. So how can we minimize the industry’s massive environmental tolls?

• CB Radio: A History: An illustrated guide to the connection between CB radio culture and modern forms of short-form communication.

• The Long White Line: The Mental and Physical Effects of Long-Haul Trucking: Nothing will wreck your spinal system like the vibration of the truck bed for hours on end.

• Long-Haul Trucking’s Billion-Dollar Cargo Theft Problem: It’s not uncommon for entire tractor trailers to go missing.

• The Uphill Battle for Minorities in Trucking: Long-haul truck driving is thriving in the United States, and remains one of the surest ways into the middle class, but minorities say discrimination is rampant.

Like other American archetypes of masculinity (the drifting gunslinger, the outlaw biker), the American trucker in song embodied cultural ideals of autonomy, freedom, competence, and non-conformity—unfettered by society’s restrictions. As Johnny Cash sang in his 1974 trucker tune “All I Do Is Drive,” the trucker had “nothing in common with any man who’s home every day at five.”

The trucker’s rebellion, however, was not the same rebellion of the anti-establishment authority-questioners of the so-recent 1960s. Instead, the protagonists of trucker songs were allied to what seemed like a deeper standard of American values. Smokey—the highway patrol—was the enemy, thwarting the trucker’s mission by enforcing speed limits. In essence, after all, the job was defined by the responsibility to provide and bring Americans they goods they needed.

When truckers went on strike to protest fuel costs driven upward by the energy crisis in both 1973 and 1979, the government quickly replaced Smokey as the real enemy.

“There are lots of dichotomies,” says Meredith Ochs, a veteran music journalist who co-hosts the Road Dog Trucking channel’s call-in radio show Freewheelin’. “They’re very anti-authoritarian, and often don’t like the government or being told what to do. But they’re also often so patriotic, so pro-military. Outlaws, but also very conservative people.”

There was also a darker part of the trucker’s blue-collar glamour; the flip side of the coin for the noble loner, after all, is loneliness.

The trucker often got to be a self-sacrificing hero, as in Red Sovine’s 1967 hit “Phantom 309,” where a driver deliberately wrecks, and dies, to save a busload of schoolchildren. More common, though, was the simpler sacrifice of family. Again and again in song, long-haul truckers’ absences take a toll on marriage and parenting.

“For the most part, it’s a really hard job,” Ochs says. “It’s grueling, demanding, lonely. It’s hard to be alone all the time, and a lot of my listeners have been divorced.”

Songs like Sovine’s 1965 “Giddyup Go,” in which a trucker returns from a long run to find his wife and son packed up and gone, lament the lonely road. Others, like Dick Curless’ 1965 “Tombstone Every Mile,” warn of its dangers.

As much as trucker country celebrates (and mourns) the loner-outlaw, the genre has conservative boundaries. There have, historically, been few female voices. Kay Adams’ “Little Pink Mack” is an exception where a woman is the driver, but more common is a female voice like Kathy Mattea’s “18 Wheels and a Dozen Roses,” in which the woman is a lonesome character on the sidelines, longing for her man. Minnie Pearl’s “Giddyup Go Answer Song” responds to Sovine’s 1965 track from the point of view of the abandoning wife who, it turned out, had to move away “to a drier climate” to die.

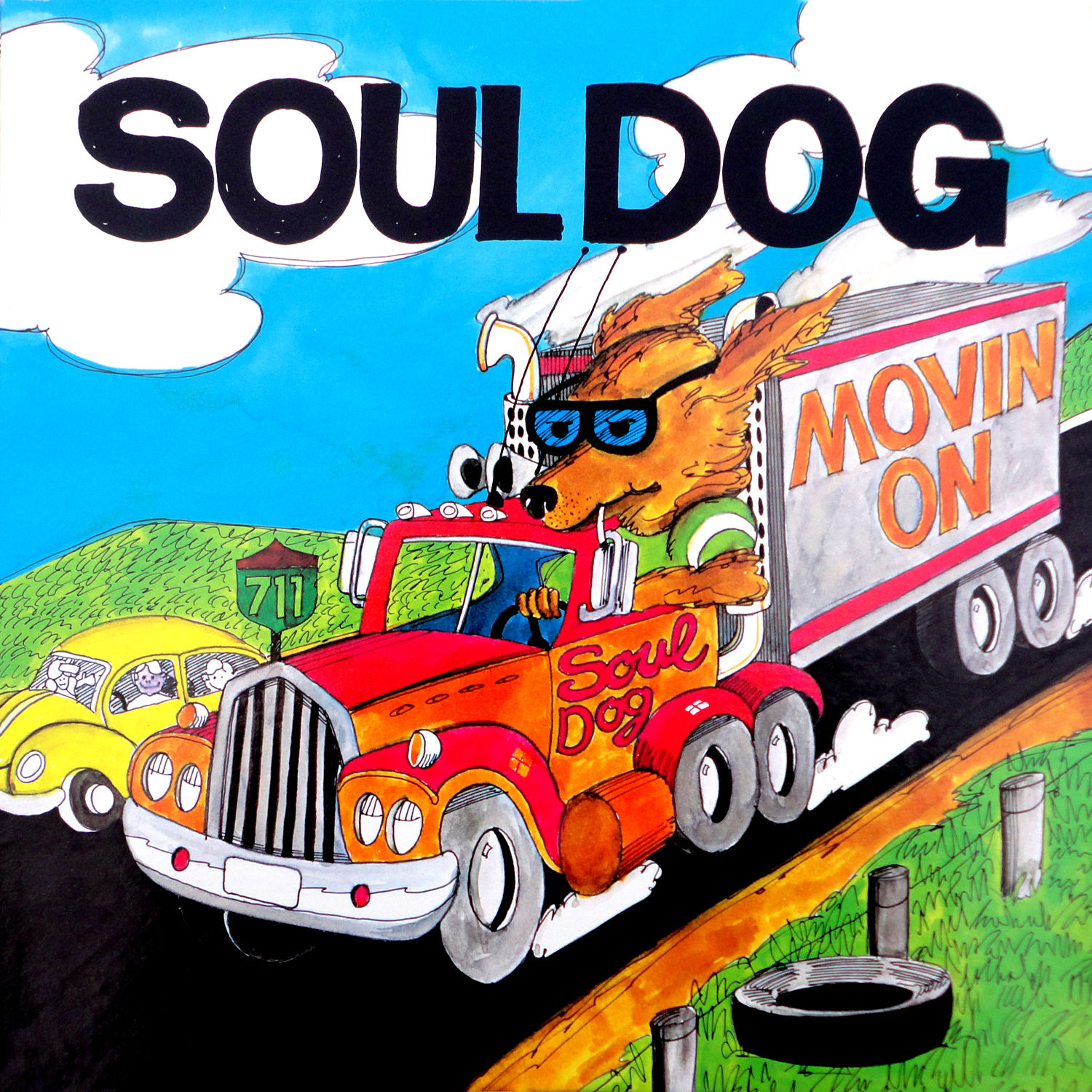

Carl Marshall is a rare black voice who recorded a trucker-themed album called “Movin’ On” as Soul Dog in 1976. Like a hip gearjamming Shaft, he introduced funk sounds to the template, using exaggeratedly Southern-accented white voices in the role of the pursuing Smokey. Similarly, “CB Savage,” a 1976 novelty song by a one-hit wonder named Rod Hart, has layers it would take a doctoral dissertation to unpack. In it, a highway patrolman distracts truckers over the CB in an over-the-top, effeminate voice that makes them too distracted to see Smokey coming to bust the convoy.

There are still trucker songs being written today, including “Asphalt Cowboy,” recorded after the millennium’s turn by mainstream country chart-toppers Jason Aldean and Blake Shelton. But the heyday of trucker country petered out in the early 1980s, and so, according to some, did the most exciting era of trucking itself.

The Motor Carrier Act of 1980 deregulated the industry, reducing the power of independent owner-operators and opening the business up to cost-cutting competition and non-union fleets.

“Now they tell drivers when to sleep, when to take breaks,” Ochs says. “Before, you trucked ’til you got tired, slept, and went back to driving. We hear all the time from drivers that it was more fun to drive back in the day.” Increased safety regulations for a job that routinely lands on lists of the most dangerous in America, she says, is, of course, a good thing. “But there’s less fodder for songwriting.”

The Keep on Truckin’ project is an effort to shine a light on the past, present, and future of the truck-driving industry in America, exploring all facets of our most pivotal, and overlooked, economic engine.