A dominant stereotype of female anger is perhaps best embodied in a caricature drawn from Faye Dunaway’s portrayal of Joan Crawford in the 1981 film Mommie Dearest, an adaptation of the tell-all memoir by Crawford’s adopted daughter, Christina.

Anyone who has seen the cult classic recognizes the depiction of a woman’s rage as a personal, vindictive series of irrational eruptions caused by inner demons. The suggestion is that women, when angry, may come to resemble the contorted, absurdly made-up madwoman who expresses anger without bounds. Children, wire hangers, and rose gardens are not exempt as targets.

Research shows that this old-fashioned perception of women’s anger as an irrational, internal engine that drives behavior continues to be pervasive.

A 2008 study from the Women and Public Policy program at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, which evaluated 222 women and 160 men, found that, after viewing videos of actors portraying job candidates, participants “were more likely to attribute women’s anger to internal factors (their personality, temperament, etc.) than external factors (like the situation, other people’s provocation).”

The angry men in the videos, on the other hand, were seen as high-level experts, according to an analysis of the study. “Women who expressed anger in a professional context were accorded lower status, lower wages, and less competence, while the opposite was true for men,” the study shows.

Little wonder that so many women are mad; there’s a lot in the workplace and in the culture to piss women off. A recent Elle survey found that 79 percent of women report rage daily just from reading the news.

But even as enduring stereotypes paint female anger as personal and irrational, its main expression these days appears to be public-spirited (and highly rational) political advocacy. Right now, the most visible expression of female fury is the way that women are organizing and mobilizing for better representation and treatment.

Two substantial new books by well-respected feminist authors on the subject of women and anger suggest that women are once again channeling fury for measurable outcomes in institutions, systems, and workplaces.

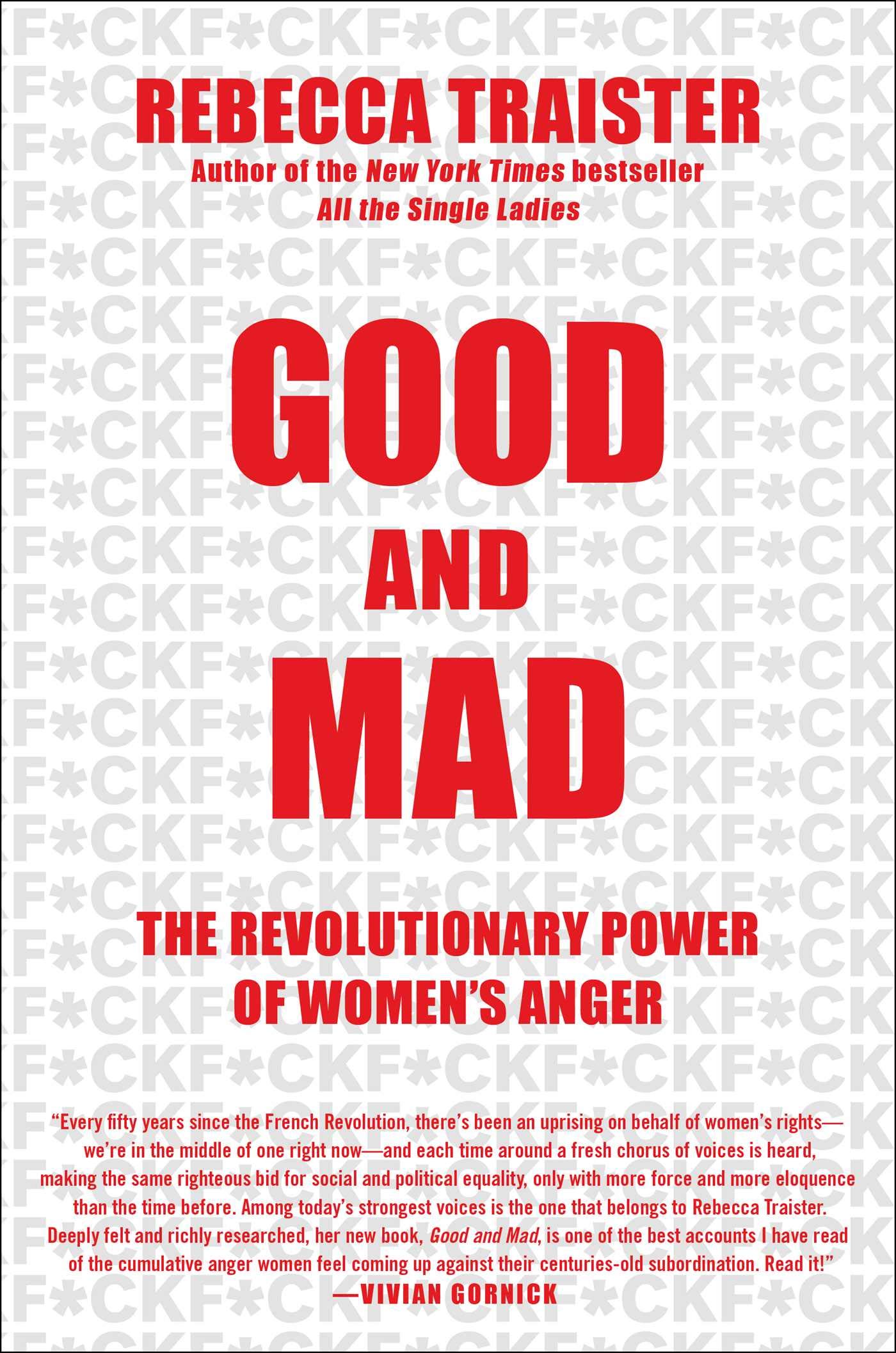

(Photo: Simon & Schuster)

In the forthcoming Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger, Rebecca Traister explores the rich legacy of female rage—from the time of Alexander the Great through the French Revolution and up to today—against the backdrop of longstanding gender discrimination, and the male tendency to dismiss or pathologize women’s anger. As Traister describes it, this collective anger has a renewed, urgent purpose lately of achieving gender, racial, reproductive, and economic injustice.

As Traister writes: “We’ve got to think about these things—history and future—because we are in the midst of a potentially revolutionary moment: not one in which all wrongs will be righted or errors fixed. But one with the potential for a big alteration in who has power in this country.”

Offering historical, literary, and contemporary context for the wave of millions of women rising in anger via Pantsuit Nation and #MeToo, Traister contends that gender-based rage crosses racial, socioeconomic, geographic, and generational distinctions.

Yet depending on your age, income level, and skin color, the anger you are allowed to express will scan differently. Women of color, in some cases, simply can’t respond in any form of anger without being stereotyped, or worse, by white men.

As demonstrated in the Women’s Marches, as well as in the recent national #BelieveSurvivors walkouts in support of Christine Blasey Ford and Deborah Ramirez, two women who have accused Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexual assault, women are continuing to strategize, organize, and demand improvements in our power structures—and who populates them.

“That was what many women wanted: a remaking of the structure, of the systems and the institutions. And given what was happening on election nights in 2017 and 2018, it wasn’t such an outlandish request,” Traister writes. “Perhaps #MeToo wasn’t going to be about retribution; rather it might be about replacement.”

Indeed, Traister’s predictions could well come to pass in the 2018 mid-term elections. According to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, an unprecedented 23 women are running for seats in the Senate, 239 women are running for the House of Representatives, 16 women are running for governor, and 26 women are running for lieutenant governor. Another 3,386 women are running for state legislative seats. These are record numbers in all categories.

In her new book, Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger, journalist and author Soraya Chemaly delivers a robust catalogue of specific sources of anger among women, including street harassment, caregiving exhaustion, sexual assault, domestic violence, maternal demands, reproductive injustice, and pervasive cultural inequities.

(Photo: Simon & Schuster)

“Saying that life is ‘stressful,’ and leaving it at that blithely dismisses women’s anger and the inequalities that contribute to that anger,” Chemaly writes. “Statistics about wages, time distributions, stress, and wealth gaps do a poor job of accurately portraying the day-to-day lives of hundreds of millions of women.”

And what is that rage demanding today?

“Anger is the demand of accountability,” Chemaly writes. “It is reflective, visionary, and participatory. It’s a speech act, a social statement, an intention and a purpose.”

That purpose is further reflected in the actions of the young women and men of Parkland, Florida, those who survived the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, transforming their anger and grief into activism, founding the March for Our Lives. Emma Gonzalez, one of the more outspoken survivors of the Parkland shooting, is a co-author in the new book, Glimmer of Hope: How Tragedy Sparked a Movement.

This is anger as motivation for change. Consider Aly Raisman, the 24-year-old Olympian gymnast whose testimony helped convict Larry Nassar, a doctor for both the United States gymnastics team and the Michigan State University team, on charges of criminal sexual assault.

“I am angry,” Raisman said last November. Speaking about the next generation of gymnasts, Raisman went on, “I just want to create change so that they never, ever have to go through this.”

Running for office, dismantling hierarchies, seeding movements, seeking to call out injustice and pursue consequences—more women are moving from anger to action, with specific game plans for change. The current movement offers the hope of sustainability, not just of anger itself, but of what anger can accomplish.