Survivors of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church have limited legal recourse. They can’t sue individual priests, because states’ statutes of limitations cut off at 10 to 21 years, depending on the state. They can’t force widespread disclosures on the scale of those in Pennsylvania without a grand jury investigation and a willing attorney general. Many can’t even confront their abusers, as some have sought to do: Of the 212 names listed on a recent Bay Area report of alleged abusers, more than half are now dead.

So Tom Emens took a different route. In 2017, the 50-year-old Camarillo resident passed up a chance to settle with the Chicago diocese, which oversaw the California-based retired monsignor who Emens says groomed and then abused him from ages 10 to 12 while in residence at an Anaheim, California, parish. Emens had waited more than three decades before telling members of his family—or anyone at all, save his wife. When he went public, he intended to be heard.

These efforts have now put him in the spotlight, at the forefront of a widely publicized nuisance lawsuit against bishops from every one of California’s 11 dioceses. (Three years ago, a similar lawsuit forced the St. Cloud diocese in Minnesota to release a trove of personnel files across the state.)

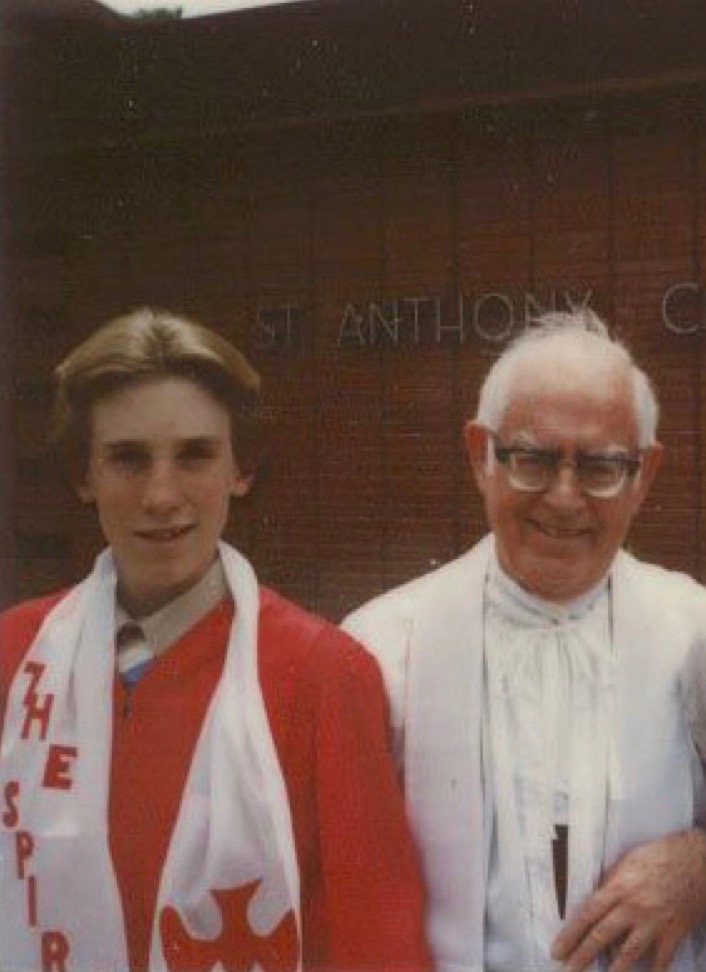

After telling his sister, his church-appointed therapist, and his lawyer, Emens found himself at a press conference in October, alongside clergy abuse attorney Jeff Anderson, telling the entire state his story: Monsignor Thomas Mohan, a retired priest at St. Anthony Claret, lived just around the block from the Emens family. He’d invite Emens to his home, or take him swimming at a neighbor’s pool. He was in photographs of birthday celebrations, at family picnics, known to Emens’ parents and six siblings—and a year after their meetings began, Mohan pushed Emens too far, he says.

Unable to hold his own abuser, who died in 2002, accountable, Emens hopes to compel each diocese in the state to release confidential records that he says will show a history of abuse and a pattern of cover-ups. He’s gone from decades of silence to giving national press conferences, taking calls from survivors across the country, and heading up a search for other victims of his own abuser. (He is in contact with one, another man who attended the church at the same time, who prefers to settle and is in discussions with another lawyer, Emens says.)

Though the California dioceses released lists of known abusers in 2004, survivors and advocates believe that those numbers were widely underreported. Emens had never seen his abuser’s name on a list or an official report, until now.

Pacific Standard spoke with Emens about why he took this chance and what the lawsuit means for him—and for abuse survivors across the state.

When did all of this start?

[My family and I] all went to St. Anthony Claret, the Catholic church closest to our house. My first contact with [Monsignor Mohan] was just him walking around the block. He was a staple in the neighborhood. He came to our house, and because he was a monsignor—I had never met a monsignor—it was kind of like a rock star. Eventually (I could never figure out how I would have ended up at his place, alone, at all) I remember a long period of time where there was definitely grooming going on: us being together, and nothing really happening.

It’s strange—maybe some people can’t understand this, but I struggled with telling the Chicago diocese. They asked me to describe who he was, what he was like, and I said he was a very sweet, gentle man, kind, charming. I adored him, and I know he adored me. There was a relationship. I was literally the golden boy. I had never gotten treated as nicely as he treated me. Being from a family where you eat what’s on your plate because that’s all you’re going to get, to have whatever you want, that’s kind of a big difference. I know I gravitated toward it. He had me for that period of time.

(Photo: Thomas Emens, Jeff Anderson and Associates)

When did that change for you?

It changed when he pushed too far. It was probably within a year. I brought [my lawyer] my report card from seventh grade. In Catholic school, you’re graded on “Christian behavior.” One of those grades was a C. I was a straight-A student, but I started getting in trouble. I got detention a couple times, I got suspended. I think I was just fighting back.

Did you ever think about telling anyone?

I think there was probably more shame than anything. I knew enough to know that no one would believe me. If I were that 10-year-old boy today, I would have screamed, yelled, and said something happened.

What was it like, finally telling your family?

It was great, but I didn’t realize how hard it hit some of them. One of my older brothers was in tears. Overall, I think they did a good job of taking it in stride and giving me support when I needed it. I’m a very strong person when it comes to dealing with this on my own, partly because, at a fairly early age, I stuck my arm out and said, I don’t want to be close to anybody. Even to this day, I struggle with that. I try not to get too close to anybody. I wouldn’t say I have close friends, period. Maybe that’s residual [from] what happened to me. I don’t want to feel anything, I don’t want to feel connected, and I want to have control.

So how did this lawsuit come about?

[After going public in 2016], I immediately looked up to see who I could talk to about it, from a legal standpoint. But I found out that I was out of luck because of the statute of limitations. I didn’t actually talk to anybody else until the early part of this year. [A representative from Chicago diocese] called and said Chicago had been settling a lot of cases with “no legal legs,” as they put it, in advance of any sort of potential window to settle with some victims. I said I was not interested.

The biggest thing driving me at that point was what I had discovered about [Mohan] as a priest. He was here in California for 20 years. [There was no] oversight—he was allowed to have underage visitors in his private residence. You can never have a kid over at the rectory, visiting with a priest. So here I am going through therapy, and my therapist said this is good, this is part of your healing; you have to get these answers. I was driven more by the unknowns. You have to answer these questions.

Earlier this year, I got on the phone with [lawyer Jeff Anderson]. He said, “There is another angle we can take; are you interested at all in putting your name on [the public nuisance lawsuit]? Because you can’t go as a John Doe. It’s risky, but it might force the dioceses to give up the names.” I was immediately interested, from the standpoint that we could get some information. There wasn’t going to be any sort of damages attached to it. He gave me a day to think about it. I didn’t really need it. I ended up saying, “Yeah, let’s do this.” Everything happened really quickly. I look back at it now and I think this probably will be my only opportunity.

Why was your feeling to go forward with this so strong—that you shouldn’t settle?

The biggest part of that was that I found another victim. Whenever there is a release of names, the dioceses will inform all the individual churches that they serve. So that was my goal: I set out to get his name out there. Having found the other victim, I thought, we have this sort of brotherhood between us. He’s on the other end of the spectrum, where he doesn’t want any sort of public acknowledgement of it. He just wants to get past it. But I think what he wants more than anything is what I want: papers, or some sort of acknowledgement.

Did you ever expect that you would be in the position of being an advocate?

Never. At one point I remember talking to Patrick Wall [a consultant and advocate for survivors], maybe two or three weeks before the press conference, and he said, “I just want to make sure you’re clear on the direction you’re going.” I said, “What are you talking about?” There are different strategies and things we can do. I said: “Patrick, I’m a spear. Throw me when you’re ready.”

I figured I really didn’t have any legal legs to stand on. The only hope I had was the chance that this particular law firm knew what they were doing with this lawsuit and could do it in the right way, and had success with [similar suits] previously. I felt good doing all that, but I had no idea that I would be in the company of people who were doing the same thing.

You went from not having told anyone, to having this kind of everywhere. What’s the adjustment been like?

It’s good and it’s bad. The good days are when I feel the victories, and another secret is exposed. Then there are days when I’m like, even prior [to coming forward], you’re pushing it down, you’re pushing it down, you’re pushing it down, trying to keep it at bay, and you can’t. There’s no way to control it. It’s no different than a trauma of any kind. It’s gotten better because of therapy. There are cycles, is the best way to put it.

What do you hope to get out of this, ultimately? What’s the best case for you?

Ideally it would be a complete house-cleaning of secret archives. I would never want to have any institution controlling or hiding criminal activity of any sort, regardless of what it is. I would want the Department of Justice to go in, seize those documents, go through, and say there’s some people here who are still practicing or never faced justice. The bonus of all that would be if what happened to me could be revealed too [in the documents].

I’d prefer that it gets cleared up completely, and that we never have this discussion about, “What’s in the secret files? Are you going get [information] as part of your lawsuit?” I shouldn’t have to do that. I shouldn’t have to be the one. That’s the bottom line. No victim, nobody outside the church or law enforcement, should have to step forward and say, hey, let’s do the right thing.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.