Sometimes when I am standing in front of my class explaining that essays need a well-developed argument and a conclusion I feel disingenuous. My story is an essay without an ending.

It began in Paraguay 28 years ago, when, after a cancer scare and a series of failed relationships, I decided to put my life in order as best I could. And so, in 1987, armed, finally, with a clean bill of health, I applied to an adoption agency that dealt exclusively with Latin America. Ten months later I was on a plane on my way to meet the baby who would become my son. I named him Noah.

The story I just told is the one I tell most people. It has a beginning, a middle, and an end. But within this story are the threads of other stories, the ones I went after and failed to grab, the others I turned away from because the trail went dead or because I just didn’t want to know them.

“He had no name,” the lawyer who handled our adoption case told me, “so I gave him my father’s name for his passport. It is also my name.” And I had given him yet another name. I looked down at Noah. So small to already have two identities, two mothers, and, soon, two countries.

The day we left Paraguay the lawyer handed me Noah’s passport. Under Place of Birth the passport office had written Bella Vista—not Asuncion. “It was easier that way,” the lawyer said.

As we waited in the summer steam of Asuncion for lawyers, doctors, the United States Embassy, and the Paraguayan government to complete the necessary paperwork that would seal our legality as mother and child, I walked through streets ringed with military. Alfredo Stroessner, the dictator who had ruled Paraguay for 34 years, was facing his eighth and final election. The presence of the army—and the lack of a visible culture on the streets or in the stores—spoke to an increasingly fragile regime in a place ready for change. That year, Stroessner won the election but lost the country. He was forced out in a coup the next.

Stroessner had little to do with my life in those days. I was learning how to be a mother, both for Noah and for myself.

I wondered about his birth mother. She was so much a part of this story. According to the lawyer, she had journeyed in from one of the villages to work for a family in Asuncion, where she got pregnant. After the baby was born, she left him with the family while she went back to her village. She told them she would come back.

She never returned. “That’s when I came into the picture,” the lawyer told me.

About the father little was known. Had he been one of the men in the house where Noah’s mother worked? There were questions no one could answer—or no one I had access to.

The day we left Paraguay the lawyer handed me Noah’s passport. Under Place of Birth the passport office had written Bella Vista—not Asuncion. “It was easier that way,” the lawyer said. “There are too many children leaving the country who were born here in the capital.”

The last thing I remember about that night was the butt of the guard’s rifle in my back as Noah and I passed through security. As we said our final goodbyes the social worker handed me a slip of paper with her address and phone number on it. “If you ever want I think I can help you find the baby’s first mother,” she said.

It was the thread of a story. I took it back to Tucson with me. The social worker’s name and address still sit in my address book. In 28 years I have never done anything with it. Should I have? Should I now? I can’t answer that. I think part of me was busy constructing another story for Noah about his Indian heritage and how his tribe fought against the slave trade in the 17th century. That much I knew. And so, in our small family of two, I began to weave Noah’s story in with the larger one of the history of South America. I told him that he was a warrior and that he should be proud.

I think he was.

Maybe I just didn’t want to complicate one story with another.

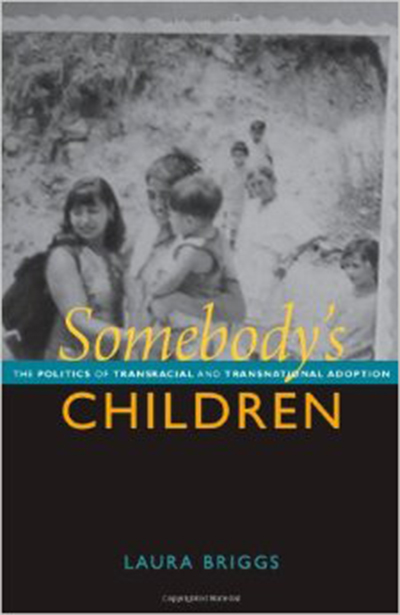

But there was no escaping it. Our present seemed fated to bump up against Noah’s past. Years later a friend of mine, Laura Briggs, was writing Somebody’s Children: the Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption, a book that told a story different from the one I had composed. In it, she argued that, between 1973 and 1983, there was a significant increase in adoptions from countries in Central and South America—Paraguay among them—with right-wing governments with close ties to the U.S. Each was fighting leftist insurgents, those fights resulting in disappearances, kidnappings, and human rights violations. Children were being taken and sold, often with government complicity.

What was I going to do with this information, with this thread?

Laura’s story made me question my own. Was Noah a part of what had gone on in Paraguay at the time of his birth?

The story I just told is the one I tell most people. It has a beginning, a middle, and an end. But within this story are the threads of other stories, the ones I went after and failed to grab.

I had adopted Noah after 1983, later than the period Laura had concentrated on in her book, but Stroessner was still in power at the time. Was Noah the result of something more than a young girl too young to take care of her baby? Had something else happened in that village that I didn’t know about? The story I shared with Laura was the only one I knew.

“That is what you were told,” is all she said.

Since 2010 we have said nothing more about it. It would have created just more spaces that no story could fill. And I worried about our friendship. I knew too little to counter Laura’s version but too much to resist it completely. All I could do was hold on to the story I already had.

Over the years my son has turned down all offers to visit the country of his birth, first as a high school graduation present and then as a graduation gift from college.

This wasn’t the way the story was supposed to pan out. Other children were going back to their birth countries and discovering their culture. Noah was constructing his own identity, his own story, independent of what our friends with adopted kids were doing or what I thought he should be doing.

It has been 28 years now since I passed through security in Asuncion with my son in my arms. Most of the time the answer I give when asked about the two of us is the one I have always given.

And maybe that is OK.

Still, though, I think often of the country my son was born into and of the young girl who was his first mother. Was she the victim of a rape or of a youthful love affair gone wrong? Did she get caught up in political forces much larger than herself?

In hindsight I think I understand what the butt of that rifle in my back at the airport meant. “You’re stealing our children,” it said.

Someday my son may wish to tie all of the strands of his story together. Or he may wish to leave them as they are, hanging threads that have been woven into a family.

Perhaps those neat endings are only the stuff of which college essays are made.