The idea that there are “lanes” for presidential candidates—that is, consistent groupings for Democratic primary voters’ second choices—has followed the cycle of many fads: It was hot, then it was not, and now there may be some re-assessment of it. Last week at FiveThirtyEight, Nathaniel Rakich examined some recent polling data on the Democratic presidential contenders and found evidence for different candidate lanes: Supporters of former Vice President Joe Biden tended to list Senator Bernie Sanders as their second choice, and vice versa. There seemed to be a similar relationship between supporters of Senators Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren.

The exact nature of these lanes, Rakich noted, wasn’t clear. (And indeed, the patterns were somewhat unexpected, given that Sanders and Biden don’t exactly emanate from the same places in the party.) There could be an “educated white liberal” lane, or an “experience” lane, or an “electability” lane, or a “fresh face” lane, or something else. Also, as Rakich explained, it’s easy to overstate these lanes, which are far from rigid or durable, and also are defined by voters who do not yet have well-informed opinions about the candidates.

Given these considerations, I’d like to suggest another way of looking at groupings of the candidates. There are network “clusters” of candidates favored by different groups of activists.

Since last December, I’ve been conducting interviews with Democratic activists in the early primary and caucus states of New Hampshire, Iowa, South Carolina, and Nevada, as well as the District of Columbia. Roughly three dozen people regularly participate in this survey, including campaign workers, party officials, and longstanding volunteers who follow politics closely and have had far greater exposure to this presidential race and its candidates than the typical Democratic primary voter has. Their opinions are about as well informed as could be realistically expected of anyone at this point.

One of the questions I’ve been asking them is, in addition to whether they’re committed to supporting a presidential candidate, which candidates they’re considering for president. They can name as many candidates as they want for that answer—most list between two and five candidates. This gives us a chance to see which candidates are clustered together in the minds of political activists.

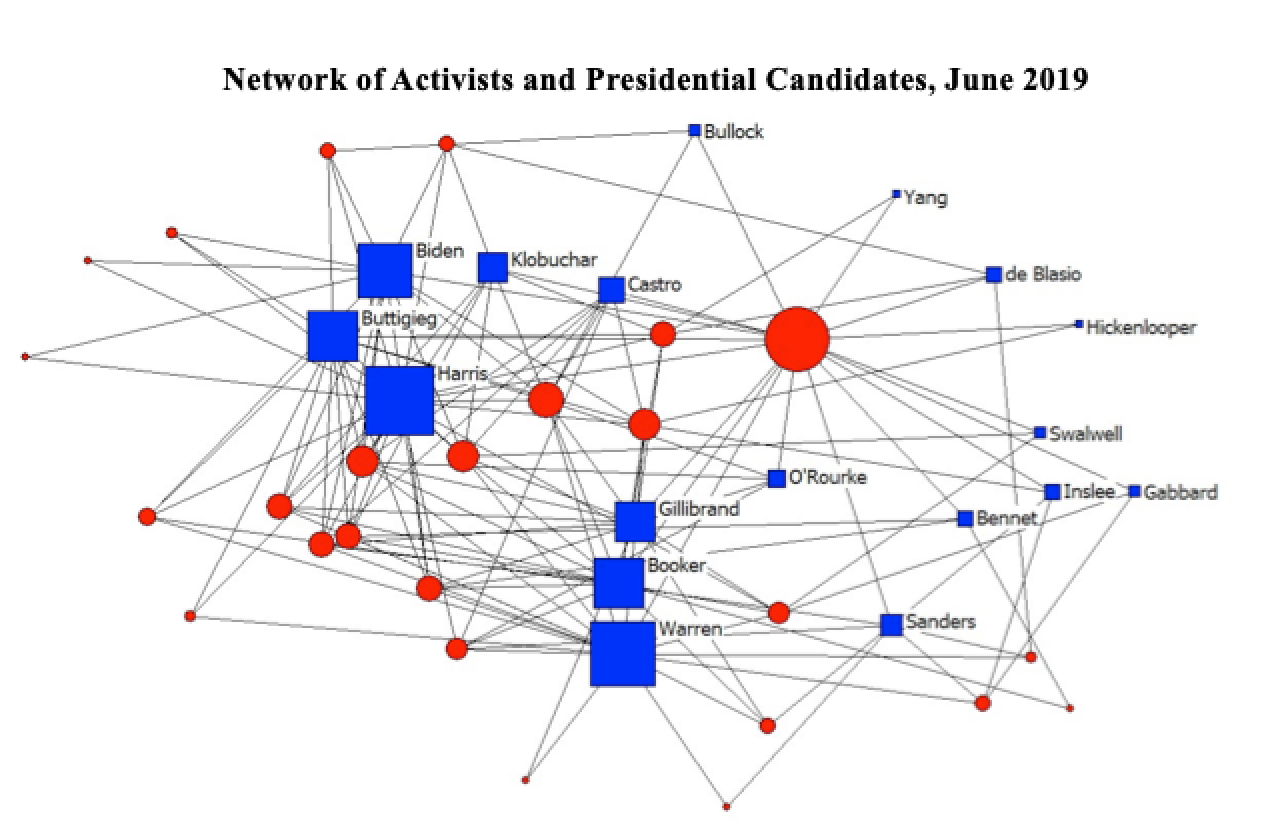

I constructed the graph below from my early June of 2019 survey using the program NetDraw, which is designed for depicting social networks visually. In the graph, the blue squares are presidential candidates, and the red circles are the activists I surveyed. The black lines indicate that an activist has named a particular candidate. The nodes are weighted in size based on the number of candidates named or activists who named them. Kamala Harris, for example, has the largest square of all the candidates because she was named by the most activists as someone they are considering. (She has been at or near the top of activist mentions since I started conducting this survey last year.)

What should we make of this map? Among the more popular candidates (the larger squares appearing in the left half of the graph), there seem to be two distinct clusters. One consists of Biden, Harris, Senator Amy Klobuchar, Representative Julián Castro, and Mayor Pete Buttigieg. Another cluster consists of Representative Beto O’Rourke and Senators Elizabeth Warren, Kirsten Gillibrand, and Cory Booker. Meanwhile, in a cluster largely by himself is Bernie Sanders.

The distinctions between the two main groups here is not inherently obvious. It could be an ideological one: The group on the left is seen as somewhat more moderate than the group on the right, although Cory Booker is not usually seen as an ideological leftist.

The fact that Sanders is more isolated is notable, however. Indeed, Sanders is something of an odd case in my survey, as he has a substantial number of activists who are committed to him, but very few outside that group who are considering him. He might seem to constitute his own lane or cluster here, with his supporters generally not looking at other candidates and supporters of other candidates generally not looking at him.

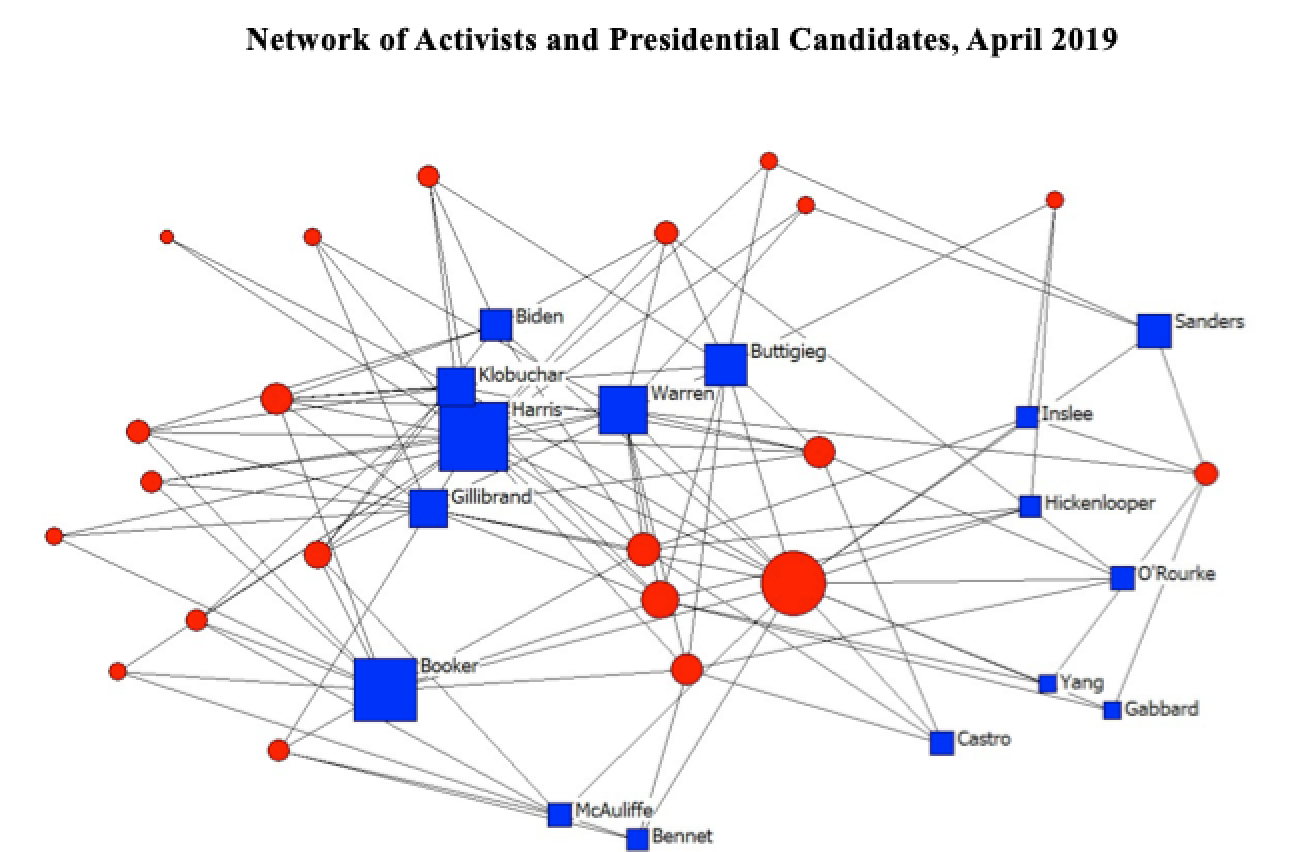

I constructed the graph below the same way as the one above, only using the results from my earlier April of 2019 survey. This is almost the same group of activists answering the questions, although the list of candidates under consideration was slightly different at that point. Conducting this examination of the clusters at multiple points in time gives us a sense of how durable these groupings are and how they may have shifted as people learn more about the candidates.

What we can see is that there isn’t a lot of consistency in these cluster designations. Those who were in different clusters in June tended to be in the same large cluster back in April. Booker, for one, appears popular but relatively isolated at this point. The one main consistency between the two surveys is Sanders, who again is off at the right of the graph with few ties to supporters of other major candidates.

I will be continuing this survey in the coming months and plan to repeat this analysis to see if candidate clusters are becoming more defined with time. At least for now, though, it’s difficult to see whether these clusters have important factional lines that will define voting in next year’s primaries and caucuses. It is also difficult to see how Sanders grows his support beyond his enthusiastic base of supporters. But again, these clusters are hardly carved in stone.