“To find a home in my body is to tell a story that doesn’t exist,” Porochista Khakpour writes in her new memoir, Sick, an eye-opening narrative of living with late-stage Lyme disease and her lifelong search for a diagnosis. Khakpour had been sick for most of her life with the nebulous afflictions that Lyme creates—from cognitive fog to lethargy to insomnia to dizziness to inoperable limbs—without being able to pinpoint the illness until it was too late. “It’s thought of as the disease of hypochondriacs and alarmists,” she writes about the difficulty in recognizing that these disparate ailments are all symptoms of the same disease: Lyme, which comes from deer tick bites that can be “smaller than a speck of pepper,” but that can cost a single patient as much as $200,000 in medical bills and the nation as much as $1.3 billion per year.

The difficulty in diagnosing a disease that presents itself with widely varying symptoms has led many chronic sufferers, predominantly women, to “not being taken seriously by those who [have their patients’ lives] in their hands,” as Khakpour states. She chronicles her distressing years of bouncing between quacks who sell her placebos, Scientologists, holistic healers, acupuncture and bee venom therapists, and doctors who write her off as hysterical when they can’t make swift diagnoses. She is put on every kind of mood-stabilizer, painkiller, and sleep aid imaginable, and the subsequent years spiral into a cycle of tapering off one drug only to become addicted to another—each cycle culminating in paranoia and thoughts of suicide.

Throughout these years, Khakpour travels to new cities that bookmark the pages of her mysterious sickness. In chapters with titles like “Iran and Los Angeles,” “New York,” “Maryland and Illinois,” and “Santa Fe and Leipzig,” she organizes her life by place as she constantly relocates in her often-fruitless search for a cure and a home. “I didn’t feel right, that I knew, but I also knew it had been years since I’d understood what that felt like,” she writes. “I had no idea what normal was.” She floats from toxic relationship to unstable friendship to hobnobbing with drug dealers in her desire not to be left alone with her illness. “Just like changes of location, my boyfriends would be how I could untangle from my own hopeless interiority.”

An “infant of the Islamic Revolution and toddler of the Iran-Iraq War,” Khakpour was born in Iran and has experienced the post-traumatic stress that often comes with being a refugee child moved from place to place, and the sense of otherness that comes with being foreign-born in an increasingly jingoistic America. In between the chapters are “interludes” that offer Khakpour’s perspectives on body image, bisexuality, support groups, being the target of racism and sexism, and the endless search for a home among all these identifiers. In one particularly moving passage, she writes: “I sometimes wonder if I would have been less sick if I had had a home.”

Khakpour talked to Pacific Standard about her memoir, living with Lyme, experiencing otherness as a refugee, and the concept of home in her life and writing.

Lyme has been in your life since perhaps childhood. Why is now the time to tell your story?

Since my definitive 2012 IGeneX test results, it has been a huge part of my life. I don’t know when is a good or bad time to tell the story. Readers of mine wanted this yesterday.

Are you afraid your illness will define you as a person or overshadow your other successes?

I think it is important that I not worry about such things. It is definitely possible. I lose out on jobs and opportunities and awards and all that stuff that I am qualified for all the time. Is it because I am a woman? Is it because I am Iranian? Is it because I am chronically ill and at times disabled? I can’t go down those roads anymore. It is poisonous. Shame on anyone who will let what they don’t understand about me define things—that’s their problem, not mine.

And while all my identifiers are a part of me, I don’t think any of them define me, exactly. I am many things. I am complicated. So are you, so are all of us. The minute I feel defined or branded or boxed in, that’s when I know I have to move on. That’s not reality—not mine, at least; that sort of convenience is more like commerce.

Your earlier works are novels. How hard is it to write memoir as a novelist?

It is much harder. I found it incredibly painful and at times very confining. I had some experience writing essays for many years, so I had a way in of thinking of myself as a character. But that’s easy to sustain and to play with for 1,700 words. Seventy thousand words is a whole different game.

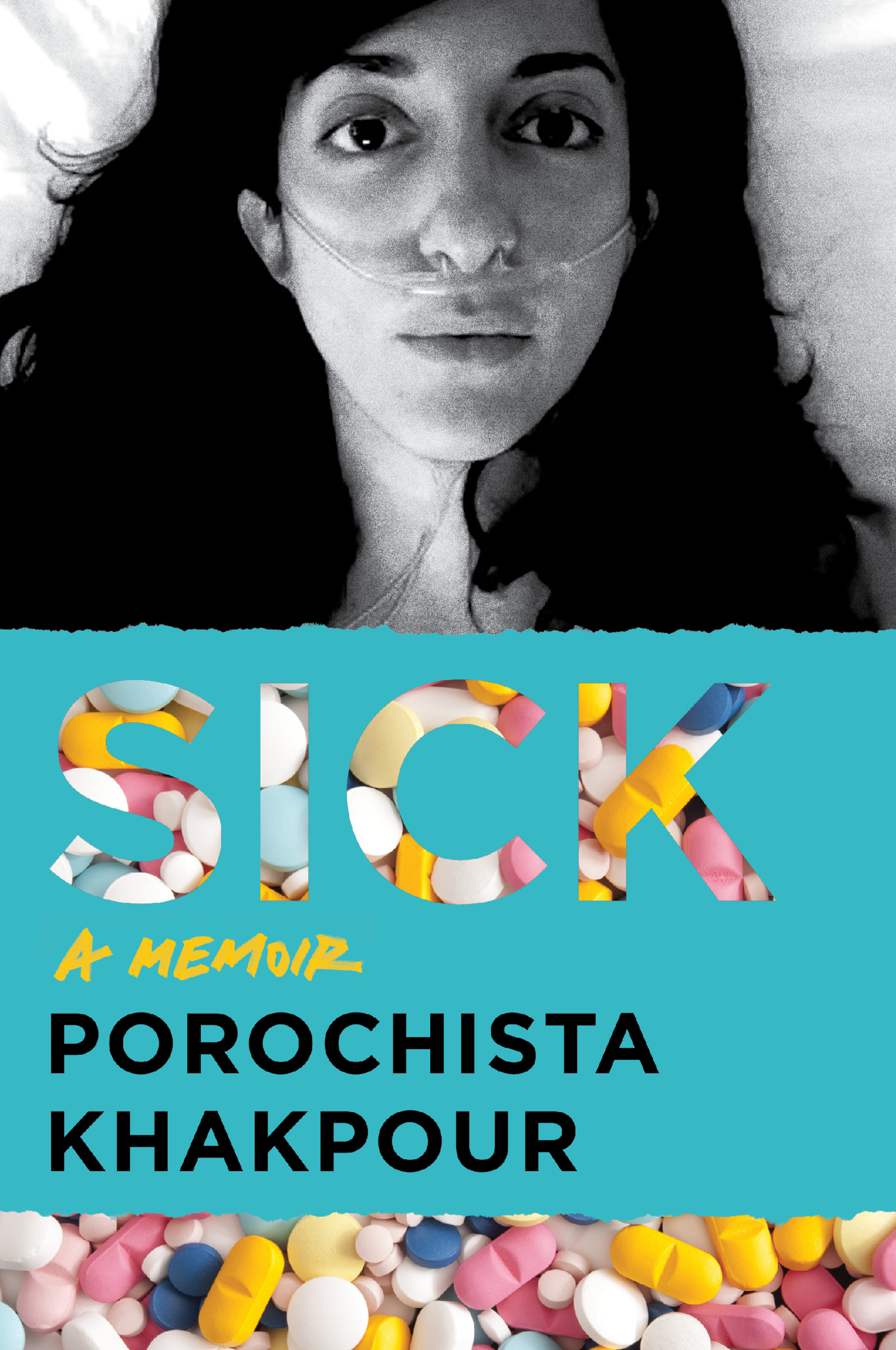

(Photo: Harper Perennial)

Parts of the book read like a stream-of-consciousness fever dream. How scattered were your thoughts while writing it?

I wanted it to be even more raw and messy and diary-like, actually—that is the experience of my illness very often—especially as I imagined this being a chapbook of sorts originally. It’s probably more normalized because of the publishing house and its editors. I also wrote much of this book while in therapy for a concussion on top of a Lyme relapse—almost as hard as doing these interviews, with lead and mold toxicity on top of Lyme!—and, well, it kept me alive. Alive-ish, at least.

Several people mentioned Lyme before your official late-stage diagnosis came years later. Do you ever kick yourself for not pursuing it earlier? Any regrets in that realm?

I did pursue it as best as I could. I pursued everything. Maybe I wasn’t tough enough to fight. Maybe I felt that as a woman I had to be agreeable and not too troublesome at moments. But in the end, I did fight, and I got my diagnosis. Imagine all the people who don’t. Who live their lives thinking it’s one thing, when really it’s something else. I have a lot of regrets, but not in this area. I did the best I could. Our system should not have required that much of me.

Sick is divided by locations, with place playing a supporting role in the narrative. Why did you decide to focus on location-as-illness?

It seemed like the only way to tell the story. It’s a mystery of sorts. The external was a sort of roadmap for the internal, at best, although you could say it was also a distraction because, as they say, wherever you go, there you are. I was looking for answers or a place to be, but also looking for myself, as so many clichés go! I have come to respect certain clichés greatly.

Do you feel that you’ve left pieces of yourself in these different places?

It’s funny. Few of them have ever gone away. I constantly return to all of them … except Germany. I think I have a misdemeanor there on file for not paying the fine for my mother sending me a bottle of Calms Forté from the United States. Sigh.

Your parents told you that your stay in the U.S. was temporary, that you’d eventually be going “home” to Iran. How much of what home is to a person comes from permanency or nomadism in our childhoods?

Any refugee like me, especially one who found her home from political asylum, probably has a pretty fraught relationship with home. My family was always going from one place to another in my early childhood, and I have never quite gotten out of that. But I am rather tired. Nomadism, indeed. I am 40, and I would like to go home.

Your parents are sometimes depicted in a harsh light. How difficult was it to write about your living family?

I hope I appear in a harsher light. And the doctors and many more! I don’t want them to look bad, but I wanted to be honest too. No one is their best self in these messes. It is stress times a million.

Where do you feel most at home now?

This is my current nightmare: I have been displaced from my beloved due to some of the horrors of gentrification. In this case, my old building had several units that had never been brought up to code above and adjacent to me, and it caused a mess of lead and mold, so I had to leave this spring. It caused incredible Lyme problems—it nearly killed me.

You now know others who have Lyme; author Esmé Weijun Wang and several others are counted among your friends. How do your experiences compare?

Esmé is a true sister, like my friend, Suleika Jaouad. I would be nothing without these friendships. I just spent three weeks in Esmé’s guest room in San Francisco in unbearable pain at times. She has been there for me in amazing ways, but we have different experiences. For instance, we joke that our days in IV wards are in shifts: She is great in the morning, and I am great in the evening. I have very low blood pressure; she has high. I can be very yin; she can be very yang. I can go on! But we complement each other quite magically—many psychic things and more.

(Photo: Sylvie Rosokoff)

Do you still feel that sense of otherness as an Iranian refugee that you experienced early on, and how has the current American atmosphere affected that?

Always. It is only highlighted more now. I cried in an IV room the other day with Esmé when some white lady kept asking me about Iran. It was so racist and benevolent at once, that weird American passive-aggression about those they think don’t belong here. I mean, I’ve heard this stuff my whole life, but it was just too much for me that day.

You talk about the first person who died in your life—your aunt—and how that affected you. Do you think there’s something particularly difficult about witnessing death at a young age?

I am never not horrified by death. It never gets easier. I am perhaps very immature about this all. I think death is fundamentally unfair. Is it my worst fear, though? No. Depression is my worst fear.

Ghosts are a reoccurring image on your pages. Do you see or believe in ghosts?

I like ghosts as a metaphor for the outsider. I wish they were real; that would be my preferred afterlife plan. I’d love to observe and haunt with little involvement—I guess that’s what being a writer is.

Bisexuality is briefly mentioned in your back few pages, almost as an afterthought. Was this a conscious decision?

It’s in one of those weird “interlude” sections that came much later than the rest of the book. I started to think as a reader of the book, not as a writer. What else would people want to know? What was not in there? What is relevant? So much about 2017 and 2018 made me want to add things—the conversations around intersectionality, this administration’s horrors, health care, etc. I felt sexuality needed more of a place in this book, so I explained why it hadn’t had one. And that has to do with privilege, heterosexual privilege. But that’s never been the full story about me. So I wanted to bring it up at least briefly. It was important to me that this book be short, so perhaps I short-changed it, but I am happy to discuss it some more.

In Sick, years of your life are marked in boyfriends. You didn’t want to be alone, but the boyfriends were simultaneously constant stressors. Do you feel you ever struck a balance?

Nothing has messed me up more than time wasted with the wrong men. That’s all I can say for that. Bad men will derail you like nothing else. I am that older woman now: Beware of bad men! Surviving the world of men, I think, is a theme in this book and in some of my other work. I feel a survivor of that as much as I am a survivor of, say, a car accident.

Do you feel relieved now that you’ve told your story? Is there any new anxiety you’ve found from it?

I am relieved to have told it, and I think a part of me hoped I would be done with it when the book was done. I was wrong. I have anxiety about it, but I have a deeper anxiety about surviving this life. Book anxiety is nothing when your anxiety hinges on things like your heartbeats.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.