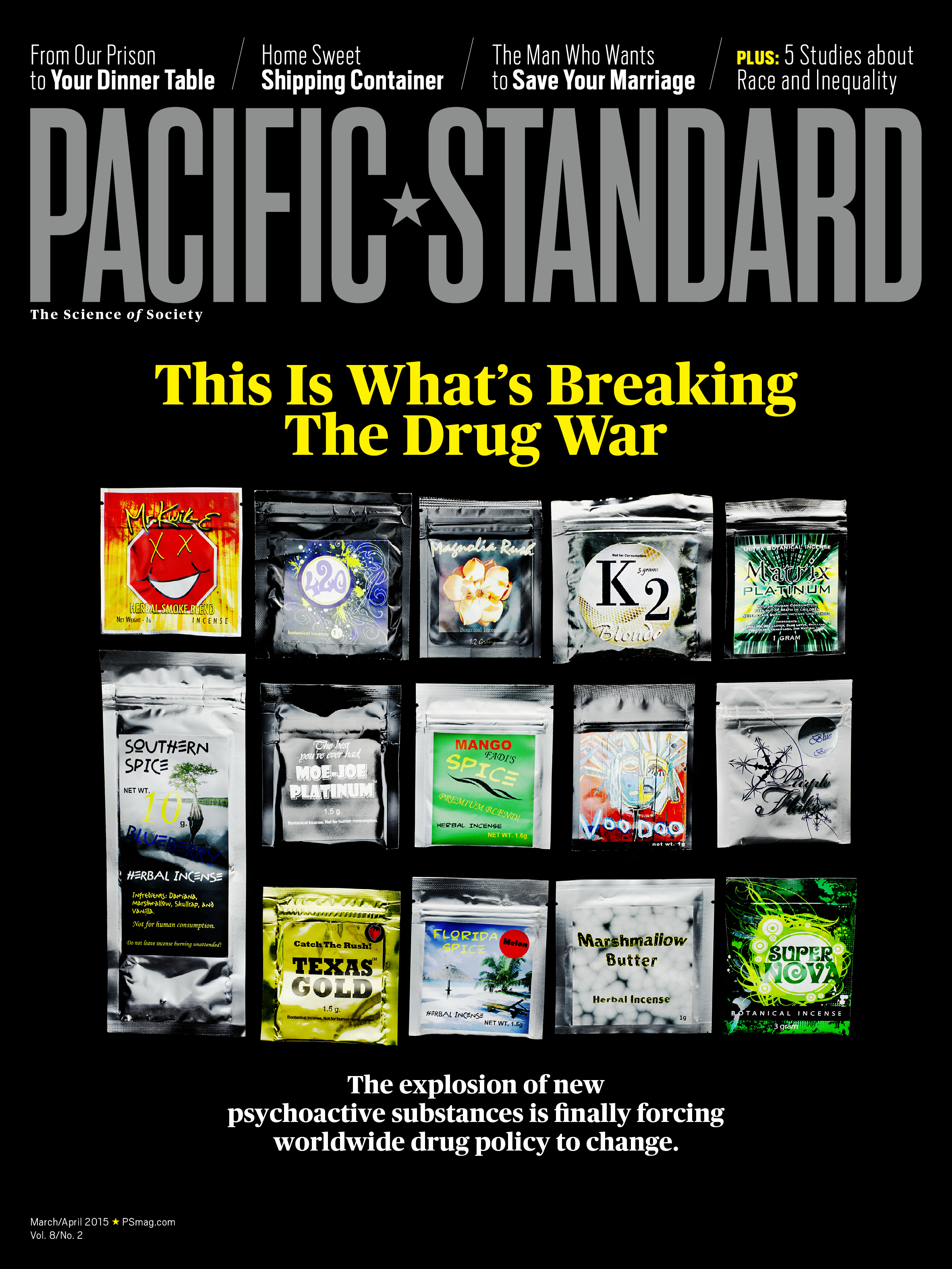

An onslaught of “new psychoactive substances”—an ever-shifting range of chemical products marketed in stores under names like “bath salts” and “spice”—has transformed the global market for recreational drugs, and reduced drug enforcement efforts to a hopeless game of Whac-A-Mole: As soon as one of these new substances gets banned, a slightly different formula pops up, untested and possibly dangerous.

In her Pacific Standard cover story, Maia Szalavitz introduces us to Matt Bowden, a flamboyantly weird New Zealand glam-rocker and drug-maker who played a key role in launching this historically viral outbreak of new drugs. And who has also spearheaded a national reform that may prove to be the only viable policy response to this burgeoning new pharmacopeia.

In 2013, New Zealand set out to become the first country in the world to establish a regulated market for new psychoactive substances. Rather than punish New Zealand for this experiment, world leaders—faced with their own losing battles against so-called legal highs—are taking careful notes.

Maia Szalavitz‘s Pacific Standard cover story is currently available to subscribers—in print or digital formats—and will be posted online on Monday, March 02. Until then, an excerpt:

For a time in the late 1990s, Bowden had worked in the “herbal highs” business—developing and selling products similar to Red Bull, as well as some containing ephedrine, the active ingredient in the now banned performance-enhancing stimulant ephedra. In part to look for new products, and in part out of a personal fascination with drugs, Bowden had trained informally with a neuropharmacologist. And while perusing the scientific literature, he had come upon a drug called benzylpiperazine (BZP).

Developed as an antidepressant in the 1970s, BZP had failed clinical trials because it was an upper that was attractive to stimulant addicts. Otherwise, it didn’t seem to have major safety issues—and it was not highly addictive. “It doesn’t reward binge behavior,” Bowden says of BZP. “The next day you feel like you don’t want to have any more for a while.” Best of all, BZP was not on the list of controlled substances in New Zealand.

The more research he did, the more Bowden thought BZP could be a safe, or at least safer, legal substitute for meth. Clubbers wanted a drug that provided energy for all-night dancing. Rather than try to squelch that demand, why not offer a different substance that served the same function but was difficult to overdose on?

In 2000, Bowden began to have modest quantities of BZP made in India, in the sort of factory where the pharmaceutical industry often outsources production of medications. His plan was to test the market for the drug by giving it to friends who used meth on the dance floors of Auckland.

What Bowden didn’t predict was that he himself would end up turning to BZP in much the same way a heroin addict turns to methadone. In their telling, the couple kicked meth by using the new drug as a kind of DIY replacement therapy. “I addressed my addiction issues at a biological level,” Bowden says. And as he watched people use BZP around him in Auckland, he realized that others were doing the same. “It was working,” he says. “People were able to get their lives together, hold down a normal job, and end their involvement with organized crime. We thought it was pretty important.”

At least in his own mind, Bowden was on the verge of becoming a drug lord with a social mission.

To read this story in print, subscribe to our bimonthly magazine, on newsstands throughout the month of March. Or you can get our March/April 2015 issue instantly on any of your digital devices.

For more from Pacific Standard on the science of society, and to support our work, sign up for our email newsletter and subscribe to our bimonthly magazine, where this piece originally appeared. Digital editions are available in the App Store (iPad) and on Zinio (Android, iPad, PC/MAC, iPhone, and Win8), Amazon, and Google Play (Android).