ALISSA BURGER GREW UP on an Iowa farm, not all that far from Dorothy Gale’s Kansas. So it’s no surprise that, even more than most children of her generation, she was enthralled by the yearly telecast of The Wizard of Oz. “I was absolutely terrified of the sequence where the face of the Wicked Witch pops up in the magic ball,” she recalls. “I would always cover my eyes and scream.”

Burger remains Oz-obsessed decades later, but the fear she felt has been replaced by fascination. In her new book, The Wizard of Oz as American Myth (McFarland, $35), she charts the various incarnations of the story in print, on film and television, and in the theater, and shows how they reflect the changing attitudes of Americans regarding the role of women, race relations, and the idea of “home.” As she pulls back the curtain on this fantastic tale, we realize we’ve really been looking at ourselves.

Author L. Frank Baum

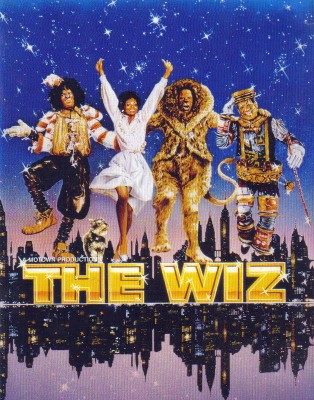

Since L. Frank Baum’s original novel, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, appeared in 1900, his magical land has been regularly revisited. To date, 39 authorized sequels have been published, including more than a dozen penned by Baum himself. The first of many stage musicals based on the material opened in 1902; its descendants include the Motown-inspired The Wiz from 1975, and the still-running Wicked, which opened in 2003. The iconic 1939 movie is just the best-known of the more than dozen film adaptations, and two more are on the immediate horizon: the animated Dorothy of Oz, opening this year, and Oz, the Great and Powerful, director Sam Raimi’s look at the Wizard’s early life, which arrives in cinemas next spring.

Why so many trips down the Yellow Brick Road? “Everybody knows the story—it’s a familiar touchstone,” says Burger, an assistant professor in the Liberal Arts and Sciences Division at the State University of New York, Delhi. “But there’s so much flexibility there, so much room for reinterpretation.”

Actresses Natalie Daradich (Good Witch of the North) and Vicki Noon (Wicked Witch of the West) from musical “Wicked,” which reimagined Baum’s wicked witch as a sympathetic character.

Burger explains that Baum’s story follows the basic journey, as laid out by Joseph Campbell, of the mythic hero: the central character leaves home, has fantastic adventures, conquers an enemy, acquires self-knowledge, and returns safely, bearing newfound wisdom. While that describes leading men from Gilgamesh to Bilbo Baggins, Baum conceived this classic scenario in one radically different way: he made his hero a heroine. Baum’s mother-in-law was the feminist leader Matilda Joslyn Gage, and according to Burger, she “was also the person who encouraged him to write down the stories he told to children.” Given their close relationship, it makes sense that the Oz books are “full of pretty strong female characters. Dorothy doesn’t have to be taken care of. Patriarchal power is questioned really dynamically, as we see the Wizard for what he really is”—which is to say, an empty suit.

Granted, at the end of the first book (and the 1939 movie), Dorothy assumes a motherlike role, helping male characters such as the Tin Man and the Cowardly Lion find their inner strength. Having done so, she is content to return home to Kansas, presumably to resume the role of dutiful niece. But Baum upends that status quo in his sequels, in which “Dorothy ends up taking Aunt Em and Uncle Henry back to Oz with her, and we see very powerful matriarchal societies—some positive, some negative,” Burger says.

On one level, the story’s various permutations reflect our evolving notions of the proper role of the woman in American society. In the original, the female character who actively seeks power, the Wicked Witch of the West, is a monster who must be destroyed, while the “good girl” heroine is torn between the longing for adventure (somewhere over the rainbow) and safety (there’s no place like home). In The Wiz, “home” is more of a psychological concept than a physical place, while the musical Wicked sets aside the nuclear family in favor of “a fun focus on female friendship.” Rather than representing the archetypes of good and evil, Burger notes, that the “good” and “bad” witches in the phenomenally popular Wicked “are presented as fully fleshed-out, rounded characters that girls really relate to.”

Burger is eager to discover whether Dorothy of Oz will present still more complex versions of these familiar characters. “The message boards on the first trailer were full of comments like ‘This looks really stupid’ and ‘That’s not how Dorothy is supposed to look,’” she says. “Each new incarnation produces that kind of initial backlash, but it gradually becomes another piece of the puzzle.” Or another brick in that golden road.