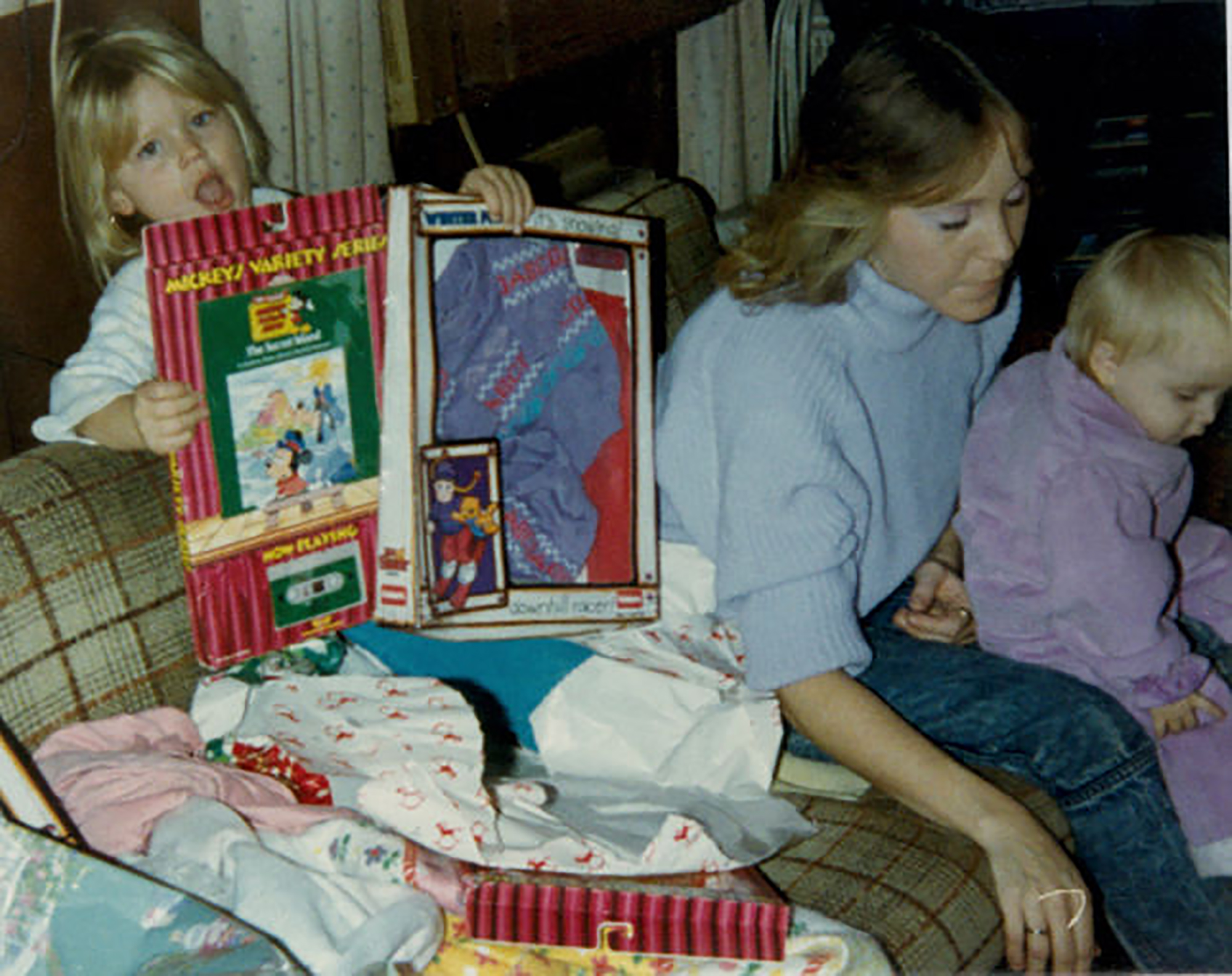

(Photo: Glenda Pleasants)

On a sweltering day in July of 2014, a van departed from the Fluvanna Correctional Center for Women and headed toward the University of Virginia Medical Center in nearby Charlottesville. The van carried an inmate named Debbie Daley, who was midway through her three-year sentence. The sun bore down on the pavement, but Debbie, a blond-haired, blue-eyed 49-year-old, was feverishly cold. Her blood pressure had plummeted, her heart rate was spiking. As the prison van lumbered ahead, the tumor on her backside caused immense pain, propelling her forward in her seat.

Fluvanna is the largest women’s prison in the state. Its modern medical building has long been considered advanced, though inmates requiring specialist appointments sometimes are transported to local hospitals. A year beforehand, after her arrest in suburban Richmond for distributing prescription pain pills, Debbie was diagnosed with Stage 2 rectal cancer. Her ensuing radiation treatment, administered by a UVA clinical team, did not work. In the next several months, as Debbie awaited chemotherapy in prison, Fluvanna officials twice failed to take her to scheduled hospital appointments.

During that time, the area around Debbie’s tumor became infected. A Fluvanna doctor declined to treat it with antibiotics, instead offering to lance near the grapefruit-sized bulge protruding below her spine. Debbie refused the treatment; she remembered her UVA oncologist telling her it was the wrong approach. For weeks she lay on her side in her prison infirmary bed, feeling as though hot coals were pressing against her bottom. “I have been real sick the past few days :(,” she wrote to her sister, Glenda Pleasants. “The sweat rolls down my face, this is all night & most of the day…. It’s times like this I need to see a MD!”

When Debbie showed up to her next appointment—this time at a different hospital in Richmond—she was met by a surprised doctor, who had not received her full medical records. And so, nearly two weeks later, on that scorching July day, an ailing Debbie sat hunched over in the prison van as it shuttled her to her original UVA oncologist. It had been nine months since her radiation ended.

Prison health care is a costly business. Incarcerated Americans are disproportionally prone to sickness, with around 40 percent battling a chronic condition. States spent around $8 billion a year on prison health care in 2011, per the most recent national estimates—likely a fifth of all correctional spending. That’s partly due to an aging inmate population: Between 1993 and 2013, the number of state prisoners 55 and older sentenced to more than one year spiked an estimated 400 percent. The situation has become a growing concern to state corrections departments, who have responded by farming out health care to private contractors in an attempt to cut costs. This contracting trend has alarmed some critics, who believe for-profit companies are more loyal to shareholders than to the inmates entrusted to their care.

Fluvanna contracts out its care, and allegations of inadequate standards at the facility led to a lawsuit against the Virginia Department of Corrections, citing the experiences of Debbie and more than a dozen other inmates. A Pacific Standard review of court filings, as well as interviews with Debbie’s legal representation, physicians, and relatives, revealed a pattern of neglect in her care at Fluvanna.

When the Fluvanna prison van parked at UVA’s hospital, Debbie, wearing shackles, was escorted inside. Upon seeing her old patient back in her clinic, oncologist Erika Ramsdale sprang into emergency mode. Debbie was “shaking with chills” and in “horrific severe pain,” Ramsdale noted. The tumor had eroded through the skin, forming a large mass. What’s more, Debbie had sepsis, a life-threatening condition typically caused when an infection enters the bloodstream.

Ramsdale grew upset to learn Fluvanna’s doctor had refused to treat Debbie’s infection with antibiotics; she knew draining that large a tumor, with Debbie’s treatment history, could do more harm than good. Her discontent became anger when she learned that Fluvanna had again discontinued one of Debbie’s pain medications, against Ramsdale’s own orders. After readying Debbie for intravenous antibiotics and chemotherapy, the oncologist called the hospital’s ethics consult service, unsure of what to do. Debbie’s condition had worsened by “significant treatment delays,” Ramsdale wrote in a July letter to a Fluvanna physician. “I remain extremely hesitant to discharge her back to Fluvanna given my concerns for medical neglect.”

Two years earlier, in late 2012, a Chesterfield County police detective pulled into a parking lot near the VIP Inn, a motel just outside of Richmond. The detective was familiar with Debbie, a resident there. Over the last couple of months, his informants had purchased a small number of Oxycodone pills from her.

When the detective approached Debbie, who was seated in a car, she confessed to being a middle-man in the local prescription-pill street market. In exchange for referrals, she received her own pills or small amounts of cash—$10 or so. The little bit of hustling she did, she told the detective, provided money so her grandchildren could eat.

Debbie was born in the Blue Ridge Mountains. After her infant brother died, her young mother walked away. At age four, she and her younger sister Glenda moved to Richmond to live with their father. The sisters were inseparable. By age 14, a precocious Debbie would take Glenda out to Jefferson Davis Highway. Colloquially known as “the Pike,” the thoroughfare bisected an impoverished neighborhood dotted with trailer parks, cheap motels, and the local methadone clinic. To Glenda, it seemed as if she had gone back in time.

(Photo: Glenda Pleasants)

Debbie was blessed with good looks; her thick blond hair and blue eyes made Glenda jealous. But she was prone to melancholy, and, by eighth grade, she had dropped out of school and was working at an ice cream shop in a Richmond mall. She met a boy, three years older, who lived in a house off the Pike with no toilet. At 15, Debbie got pregnant and became a bride. In the next decade, she bore five children with two men.

The young mother’s house became a hub for neighborhood children, who called her Mama Debbie. Beach trips and picnics were common. “You couldn’t go to her house where there weren’t 20 kids,” Glenda says. Chaos brought out the best in her. Money was tight, and Debbie cleaned houses for extra cash, spending some of it on food for her young visitors.

Debbie and Glenda loved teasing each other: Sissy, Glenda would say, What do you call a brunette and three blonds on a street corner? Regular price, four bucks, four bucks, four bucks! When Debbie missed a Tracy Lawrence concert because Glenda could not babysit that night, reports emerged that the country singer had gone home with a groupie. “Sissy, that could have been me!” Debbie joked.

Shortly after Debbie conceived her fifth child, her boyfriend went to prison, and Glenda moved in. When Timmy was born—Debbie’s last child and only son—Glenda was by her side. Glenda had never seen a person glow like Debbie did that day.

As she raised her children—and eventually helped rear seven grandchildren—Debbie charged herself with amphetamines, and dabbled in cocaine. In 2001, after wrist surgery, the result of hereditary bone-deterioration, Debbie was prescribed Oxycodone. She got hooked. Money saved for a house dissolved, and she moved with her third husband into a trailer park across from a truck depot. The couple soon separated, and Debbie made new drug contacts. One man pulled a gun on her. Glenda received calls from concerned friends. “Your sister looks terrible,” they told her. When Glenda confronted her, Debbie confided, “Sissy, I’d rather be a pill head than a methadone addict.”

Never one to complain, however, Debbie always seemed to have a plan for survival—”the kind of person who could fall in a pile of shit and come out smelling like a rose,” recalls a niece for whom Debbie once offered a bed after the teenager landed a job at the local Hardee’s. Despite her addiction, Debbie continued caring for her grandchildren, walking them to the school bus and escorting them on play outings.

More than anything, Debbie doted on Timmy, a tall, thin kid with a blond crewcut and endearing smile; Santa Claus managed to come every year, filling the young boy’s packages with video games, BB guns, and dirt bikes. Mom did all of that on her own? one daughter thought upon learning the truth about Santa.

In 2011, Debbie was arrested for distributing Oxycodone and sent to a diversion center. Timmy and a sister visited every week. After her release, Debbie found a job at a McDonald’s. Two months later, at the age of 20, Timmy overdosed and died from a pre-existing heart condition. A devastated Debbie quit her job and moved with two daughters into the VIP Inn, sandwiched between the Pike and I-95. She resumed grandmother duties, and worked the Pike pill market when she could.

So when the police detective approached her in the parking lot near her motel, Debbie knew she could not escape her history. “I did not believe that she was selling a large quantity of pills, but I knew she did sell,” the detective recorded in his report. A search of Debbie’s room uncovered a Ziplock bag with 18 Oxycodone pills, and Debbie was jailed at a local facility. Around that time, she began experiencing some bleeding in her buttocks area. She thought it might be hemorrhoids.

The debate surrounding prison health care dates to the country’s birth. In 1871, the Virginia Court of Appeals declared that “[the prisoner] is for the time being a slave, in a condition of penal servitude to the State.” From a health-care context, that philosophy was challenged 50 years later, when the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled in 1926 that a small rural county was on the hook for the cost of a surgery that saved the life of a criminal wounded during gunfire exchange with a sheriff’s deputy.

But the issue would not reach the United States Supreme Court for another 50 years, by which time the stage had been set with horror stories about inmates pulling out each other’s rotten teeth or dying in their own filth, covered in maggots. (One of the major grievances in the infamous 1971 Attica Prison riots was lack of medical care.) In Texas, a prisoner named J.W. Gamble sued the state Department of Corrections for medical neglect after injuring his back, the result of a cotton bale falling on him on a prison work farm. In Estelle v. Gamble, the Supreme Court in 1976 cited a previously established “evolving standard of decency” for people behind bars. Inmates, the justices reasoned, are entitled to health care under the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment.

But the opinion came with a twist. In order to prevail on claims of health-care inadequacy, prisoners must not merely prove medical neglect. In fact, they must clear a much higher bar: “deliberate indifference to serious medical needs.”

(Photo: Glenda Pleasants)

Because prison health care is unevenly regulated, there is a dearth of reliable data to prove deficiencies. In 2009, Andrew P. Wilper, an associate professor at the University of Washington’s School of Medicine, was one of relatively few scholars investigating the issue. Citing U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics inmate surveys from 2002 and 2004 (the latter of which is still the most recent survey of its kind with publicly available data), he co-authored a study in the American Journal of Public Health, which found that 20 percent of state inmates with a persistent medical problem had never been examined. The survey concluded: “Many inmates with a serious chronic physical illness fail to receive care while incarcerated.” In the same study, Wilper cited a 2007 Surgeon General’s report titled Call to Action on Corrections in Community Health, which stated, “Prison health is generally not funded to provide disease prevention and health promotion programs.” The document was reportedly blocked from public release by the the federal government out of fear that it would increase government spending on inmates.

In early 2013, one month after her arrest, Debbie noticed a lump on her right buttock. Over the next several weeks, it grew hot and irritated. Small holes formed in the surrounding skin, making it difficult to sit or walk. Following her guilty plea, Debbie was sent to Fluvanna. UVA tests soon revealed State 2 rectal cancer, a diagnosis that stunned Debbie. She had to get a colostomy, a surgery that reroutes stool through an opening in the abdomen, requiring Debbie to wear a bag. She worried how she might smell.

Debbie was put under the care of Ramsdale, an assistant professor with UVA’s Department of Medicine, and a colorectal cancer specialist. The young oncologist’s Kansas roots lent her a Midwestern matter-of-factness. Debbie was her first prison patient.

Ramsdale ordered a six-week course of radiation, requiring Debbie to visit the hospital each weekday. As the inmate waited for the prison van’s arrival inside Fluvanna’s processing room, the chain around her midsection irritated her ostomy, sometimes drawing blood—to the point Fluvanna eventually removed it. The guards routinely strip-searched her, which to Debbie bordered on the absurd. “I have tumors occupying all my hiding places … where am I gonna put anything?” she wrote Glenda.

During UVA exams, Fluvanna correctional officers kept an eye on Debbie, standing close enough to hear Ramsdale asking questions about prison treatment. Some guards, Debbie recalled, saw “the whole nine yards.” Her hospital gown was opened in back, which made walking to the bathroom awkward. “Not that I expect anybody wants to see anything, that’s not the point, but it’s just humiliating.”

Many days in her clinic, Ramsdale observed Debbie grimacing and sweating in her chair. “She is tearful and standing due to pain.” one doctor noted. “Pain ten out of ten.” Ramsdale prescribed morphine, but Fluvanna stopped administering it to her. Occasionally, the prison withheld Debbie’s short-acting pain medications, against Ramsdale’s orders. “Sometimes the medications would have been stopped without any notification,” Ramsdale recalled. By November, the morphine had arrived, but the radiation had failed to shrink the tumor.

The next step was discussing chemotherapy, but Ramsdale had difficulty booking an appointment with Fluvanna schedulers. For several months Debbie waited in her prison infirmary cell, a sparse box where the lights remained on all night. Lying in bed next to photographs of her grandchildren, she used colored pencils to draw Disney princesses, and watched television to distract herself. In one episode of The Fosters, she cringed at the character Callie’s neediness. One of those “poor pitiful me” girls, she thought. Gets on my nerves.

Sometimes Debbie would take out a sheet of paper and write letters to Glenda in flowing half-cursive, resolving to get well. “I can’t wait to get home & I hope you guys still want me. … I will be good I promise!! And if you need me to move @ anytime all you have to do is tell me and I can get a place of my own. … I don’t want to be a burden on anyone.”

Brenda Castañeda hopped into her Nissan Quest and sped to Fluvanna. It was 2010, and Castañeda, who often used the Quest to ferry her children to Tae Kwon Do classes, was making her routine journey to the prison, where she regularly coached inmates how to file medical grievances.

After graduating from UVA law school in 2006, Castañeda was hired by the Legal Aid Justice Center in Charlottesville, which serves low-income Virginians. The center soon launched a prisoner-rights project, and inmate letters poured in from across the state. Health care was one of the biggest complaints, and several came from Fluvanna. Castañeda, who was 30, had spent her young career advocating for tenants’ rights. She leaped at the opportunity to volunteer for the Fluvanna case.

Opened in 1998 as a flagship hub for ailing inmates across the state, Fluvanna has a 68,000-square-foot medical building. “To my knowledge there is not another woman’s facility in this country that has the type of medical/mental health building that we have,” the original warden told Corrections Today. The prison is located in the small community of Troy, near the dead-center of the state. Women from other facilities are often transferred to Fluvanna if they require heightened medical attention.

But by 2009, the Legal Aid team recognized enough medical deficiencies at Fluvanna to throw its entire investigation into it. At first, Castañeda did not know what she was getting into. Inmates alleging inadequate health care face long odds of winning in court. In 1996, in response to mounting lawsuits from inmates, Congress passed the Prison Litigation Reform Act. In order to prevail in a lawsuit, the legislation required inmates to exhaust a prison’s grievance process, often lined with roadblocks. Castañeda had never worked on anything so big, but with each visit to Fluvanna, she grew more enraged at the system, motivating her to forge ahead.

By 2011, several patterns emerged, and continued to mount. Some inmates complained they weren’t given proper medication, like the woman with HIV who was ordered to finish her old prescription despite its mental-health side effects. Some complained they were denied medication, like the prison cafeteria worker who, one inmate testified, was not given a remedy for her hand fungus. Some complained their grievances were ignored, like the diabetic woman whose unheeded complaints about foot pain led to an amputation, which caused an infection, which led to another amputation above the knee. Some complained about misdiagnoses, like the woman with back pain who was treated for pneumonia, only to discover months later that a spinal infection had caused her disc tissue to deteriorate. Some complained about delayed treatment, like the woman with an abnormal mammogram who wasn’t treated for breast cancer for 10 months. Some complained about denied treatment, like the woman who was told to rub Tabasco sauce or Vicks VapoRub on an ingrown toenail susceptible to a fatal infection. Some complained their specialist orders were ignored, like the woman with a breast mass who was never given a UVA-ordered biopsy. Some complained about mismanaged surgeries, like the woman with carpal tunnel syndrome who received surgery on just one hand, rather than both, and could no longer write.

Castañeda’s team also noticed administrative deficiencies: Pill lines were supposed to occur a few scheduled times a day, but were often delayed, requiring two-hour waits. After sick call—the process whereby, inmates testified, they paid out of pocket to lodge a medical complaint—some women waited weeks to see a doctor. Infirmary-bound inmates were isolated from human contact, blocked from educational classes, worship, and social activities, Castañeda observed. Prisoners told her the conditions were frigid, with paper-thin blankets, no hot water, and little access to food. The infirmary, according to one inmate, had feces and blood on the wall.

Castañeda had always enjoyed fighting for tenants’ rights, but something about Fluvanna felt different—almost Kafkaesque. This is life and death, she thought to herself. She assured inmates their complaints were valid. “You’re not crazy,” she told them. “This is morally and legally wrong.”

Throughout 2011, Castañeda continued her treks to Fluvanna, teaching inmates about grievance claims. Back at the office, she pored over documents detailing amputations, blood clots, and rectal bleeding. The Legal Aid lawyer grew impatient at frequent delays. With each setback (a few times, Castañeda recalled, a Fluvanna official leafed through her files and confiscated a blank grievance form) she channeled her anger into action. Would I be OK with losing? No, I would not!

By the following year, Castañeda had met with around 200 inmates. The young lawyer was convinced she had enough evidence to prove that Fluvanna showed a deliberate indifference toward inmates’ medical needs. That summer she filed a class-action lawsuit against the Virginia Department of Corrections. She steeled herself for the response.

Substandard care generally hinges on correctional budgets, and when cuts are ordered, health care is sometimes the first thing to go. Concerned over costs, more and more states—around 20 by 2012—were transferring prison care to private companies, a 2012 Washington Post and Kaiser Health News investigation found. For-profit health companies answer to different requirements for internal reports across states, making it difficult to measure their quality of care. In 2009, Kelly Bedard, an economist at the University of California–Santa Barbara, was one of the few scholars to try. Bedard focused on mortality rates (which are a matter of public record) at more than 1,000 prisons before and after each adopted a contractor model during an 11-year period ending in 1990. In a Health Economics article, she concluded: “Our findings of higher inmate mortality rates under contracting out are more consistent with recent editorials raising concerns about this method of delivering health care to inmates.”

(Photo: Glenda Pleasants)

Still, some experts argue that, if deficient correctional health care exists, then local administrators, not private companies, are to blame. “Even with for-profits you still have to have enough money to pay for the work,” reasons Dr. Nicole Redmond, a board member for Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform. “Are they cutting back on services to preserve their profit, or are they cutting back because they were never adequately funded to begin with? That’s the big question mark.”

On the day of Debbie’s scheduled chemotherapy consult in early 2014, Fluvanna officials failed to transport her to UVA. Another two months passed before she finally arrived. After that session, Ramsdale phoned Fluvanna’s doctor, Patricia Rodgers, to inquire about the missed appointment. (Rodgers declined to comment on her interactions with Debbie and Ramsdale, as did Corizon, the company that employed her.)

Rodgers told Ramsdale that correctional officers could cancel hospital transports for any reason. To avoid another mishap, Rodgers suggested that Debbie’s treatment be transferred to Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. That hospital had a secured ward reserved for inmates, and transportation would be easier, Rodgers explained. Ramsdale bristled at the idea of letting go of Debbie’s care. But another missed appointment would be unacceptable. She signed off to the transfer, but not before scheduling one final appointment for a CT scan, and for a follow-up visit, where she could say goodbye.

Rodgers was employed by Corizon Health, the for-profit company that at the time was contracted with Fluvanna and 16 other Virginia facilities. The Brentwood, Tennessee-based organization claims to be America’s largest private correctional health-care company, responsible for 240,000 inmates in prisons and jails in 24 states. Corizon entered its $76.5 million contract with the Virginia Department of Corrections in 2013, having bid $17 million less than its nearest competitor. Its financing model was pegged to the total monthly inmate population, regardless of whether they were healthy or sick. Under those terms, Corizon’s profits increased as the cost of the care it provided decreased.

Corizon has been the target of hundreds of recent lawsuits. At Rikers Island jail in New York, where up to a dozen inmate deaths had reportedly occurred as of 2015, the city’s Department of Investigation cited two fatalities possibly linked with medical neglect under Corizon in a report that year. In California, Corizon and Alameda County were ordered to pay out $8.3 million—the largest wrongful death settlement in state history, according to the plaintiff’s lawyers—after an inmate died. In Alabama, though Corizon is not a named defendant, the company is embroiled in a class-action lawsuit alleging a host of deficiencies in the state’s prisons under Corizon’s watch.

In a written email statement, Corizon chief executive officer, Karey Witty, who was appointed in 2015, said he is proud of his staff. “They are performing one of the toughest jobs in America,” he added, noting that inmates suffer from higher rates of mental illness, lack of preventative health care, substance-abuse issues, and chronic diseases. Regarding litigation, he noted: “The existence of a lawsuit is not necessarily indicative of quality of care or any wrongdoing. Malpractice suits are a fact of life for most doctors in America today, and this is particularly true in corrections, where the patient population is highly litigious.” The majority of lawsuits lodged against Corizon are either dismissed or closed, or result in his company’s favor, he wrote. “The tendency for the media and the public to focus on the exceptions—or the outrageous claims of plaintiff’s lawyers—creates a skewed and dangerous perception of the care we provide.”

As Debbie waited in her cell, prepping for her chemo port to be inserted, she wrote a letter to Glenda. “The longer here the worse it gets,” she said. “I pray every day that GOD will feel I deserve to come home. … I hate asking the Lord for too much.” Timmy’s spirit, she added, was with her.

The day of Debbie’s final UVA visit, Ramsdale received an email from a Fluvanna coordinator informing her that Debbie would not be coming in. Ramsdale didn’t know it, but Debbie’s condition had taken a turn for the worse. The area around her tumor became infected, causing it to protrude from the skin. She could not stop vomiting, and Fluvanna’s staff did not clean or bandage the open abscess on her bottom, she would claim. When she requested antibiotic treatment, Fluvanna’s medical director apparently refused. (The director says he does not recall treating Debbie.)

Still, Debbie stayed positive. Referring to her chemotherapy and release date, she wrote Glenda, “I either wanna get the hair loss done w/ B4 I come home or after I get there. … But I don’t care if I am throwing up I just want to be with you.” Later that month, Glenda visited to tell her sister that her 14th grandchild had been born on her birthday. His name was Timothy. Debbie wept.

When Debbie arrived for her VCU appointment, the on-site physician, Laurie Lyckholm, was startled by her condition. Excusing herself from Debbie’s presence, Lyckholm phoned Ramsdale and, in an upset state, said she was confused as to why a feverish Debbie was sitting in her clinic. “She had a very advanced disease, and said she had been getting good care at UVA,” Lyckholm recalls.

On the other end of the line, Ramsdale was horrified, having assumed Debbie had had a follow-up six weeks earlier. After hanging up with Lyckholm, she phoned Rodgers. The Fluvanna doctor told Ramsdale she would look into the situation and call back. But Ramsdale never received a call, and a voicemail the next day went unreturned. Nearly two weeks later, Debbie arrived at UVA in a septic state.

After tending to Debbie’s sepsis, Ramsdale called an emergency meeting and told her colleagues that Debbie had consistently arrived at the hospital with clear signs of medical neglect. On their advice, she declared Debbie an unsafe discharge. The next step was to inform Fluvanna that Debbie would not be returning to the prison in the near future.

At her computer, Ramsdale did a cursory Google search for Fluvanna’s phone number. Suddenly, something on the screen caught her eye: a newspaper article citing a Fluvanna lawsuit. Ramsdale was curious. Could what was happening to Debbie be happening to other inmates too? During a conversation later that day, a hospital lawyer confirmed to Ramsdale that she had received subpoenas for the medical records of several Fluvanna inmates, including Debbie. One name listed on the subpoenas was Brenda Castañeda.

That afternoon, Ramdale phoned Castañeda, echoing her concern that Fluvanna was not a safe place for Debbie. The Legal Aid lawyer sensed urgency in the voice on the other end of the line. It reminded her of her own—full of moral outrage. A kindred spirt, Castañeda thought.

(Photo: Glenda Pleasants)

“What should I do?” Ramsdale asked.

Castañeda suggested sending a letter to Fluvanna, Corizon, the Department of Corrections, and the attorney general’s office, putting them on notice. If Castañeda typed up a quick draft, would Ramsdale edit it? The oncologist said yes.

That night, Castañeda sent the letter to all parties, demanding that the prison take all the necessary steps to protect Debbie’s life.

As Ramsdale cared for Debbie over the next six weeks, the two women bonded. Debbie told her oncologist stories about Timmy, and Ramsdale, who was pregnant, asked questions about motherhood. “I can’t wait to meet him when he’s born!” Debbie said. Ramsdale was amazed by the inmate’s stoicism, the most she had ever seen in a patient. Despite her pain, she never complains, the oncologist thought. The respect was mutual. “Dr. Ramsdale sure has them scared to mess up where I and my medical care is concerned,” Debbie would tell Glenda. “She’s a great MD.”

Midway through her chemotherapy, Debbie was sent back to Fluvanna, after Ramsdale got reassurances from the medical team that they would closely monitor her care. Days later, she called Glenda. “Hey Sissy,” she said. “There’s a lawyer coming to see me, and I don’t know why.” Later that day she was escorted to a separate prison building, where Castañeda was waiting.

The Legal Aid attorney was struck by how ill Debbie looked; pale and gaunt, her voice soft. Fluvanna guards watched through the window as the women chatted. To Castañeda, Debbie’s complaints hit on so many points in the lawsuit—withheld medication, incorrect doses, ignored complaints, ignored specialist orders. Her story so clearly illustrates the failures of the system, the attorney thought.

Like Ramsdale, Castañeda was struck by the inmate’s stoicism—modest and gritty to the core. Through a series of visits that summer, the young attorney sat by the sick inmate like a family member, listening to her gush about Timmy and her grandchildren—”my babies,” she called them.

Debbie continued writing Glenda. She often told jokes: about the soothing moisturizing cream doctors gave her for a rash (“It looks like Crisco. I think of fried chicken every time I use it”), or about the time when UVA nurses asked if she were pregnant. (“LOL.”) Debbie wrote Glenda a list of favorite snacks she wanted from the commissary: pickles, Tootie Fruities, salsa, and fireballs.

More than anything, Debbie said she missed her daughters, who were going through their own difficulties with their families. Debbie still wondered what had fractured their relationship. “I made mistakes,” she wrote. “But I took care of my family. I busted my ass one way or another.”

She was willing to forget all of that now. “I need those kids just as much now as I did b4 if not more!” she wrote to Glenda. “GOD has been my spiritual guide & hand to hold, I just haven’t had any family human contact.”

And yet, like so many other times in her life, Debbie pledged to beat the odds once again. “Thank you for everything!” she wrote. “You have no clue how happy I am :)”

Throughout 2014, Castañeda geared up for a December trial, putting all other assignments on hold. She worked 14-hour days, digging through thousands of pages of medical records and blazing through weekends. Neighbors tended to her children during late nights in the office. Her eyes burned. She grew cranky. She forgot her brother’s birthday.

Eventually, the work yielded results. The evidence showed that approvals for specialist appointments could take weeks, and that specialists’ orders often were not followed by prison staff. (Asked why a Fluvanna physician might change UVA orders, a Corizon doctor testified: “As per policy, he’s expected to. Either Corizon or Department of Correction policy, he’s supposed to. That’s part of his job.”) The evidence showed that inmates experienced long delays in waiting for medications, or sometimes didn’t get them at all. (During a personal visit, the Department of Corrections’ pharmacy director called the situation “disturbing.”) The evidence showed that inmates faced lengthy waits for seeing a doctor, and that one inmate died after likely being misdiagnosed. (After the inmate died from cancer, the prison’s medical director acknowledged that she had not been properly diagnosed in a timely way.)

That summer, Corizon formally opted out of its Virginia contract, just over a year after entering it. The company was subsequently dropped from the Legal Aid lawsuit. Undeterred, Castañeda trained her sights on the Virginia Department of Corrections. She had a parade of inmates ready to take the witness stand with claims that their grievances were continuously ignored.

One, who was deaf, testified that she waited four months for broken hearing aid replacements, during which time she was written up for disciplinary violations, unable to hear intercom announcements. Another, who had Hepatitis C with elevated liver enzymes, was not properly considered for treatment for seven years; by then, she showed signs of cirrhosis and liver failure. Another, who had urinary incontinence, was denied surgery; her limited bathroom privileges forced her to wet herself in bed, without regular access to laundry facilities. Another, whose abnormal breathing and weight loss were misdiagnosed as early-stage menopause, was ignored when she sought help. When her leg swelled and her toes turned blue, she said Fluvanna doctors told her to stop taking birth control. Months later, in the emergency room, doctors discovered that a blood clot in her leg had traveled to her lungs. A military veteran who once taught yoga classes in prison, she is now in a wheelchair. “We made a mistake, but we’re still human beings, and it is not right,” the inmate said.

By September, Debbie felt like she was in labor—each burst of pain hit her like a succession of contractions. Still, the inmate prepared for her homecoming. “It won’t be long YAY!” she wrote Glenda. “There is so much I want to do and I’m gonna do it :). … Will U stay up late & watch scary movies with me too?” In the margin of the letter, Debbie wrote an extra note, surrounded by a cloud border. “I LOVE YOU SO MUCH SIS.”

But the next month, Debbie learned the chemotherapy had failed. Her tumor had grown, pushing against her bowel and blocking her kidney tubes.

When Glenda visited, Debbie limped down the chilly corridor in her oversized jean jacket. The prison had not given her pain medications for the past few days, and Glenda noticed that the sockets around her sister’s blue eyes had hollowed. Her once-thick hair had thinned, and her skin looked gray. Glenda started crying.

(Photo: Glenda Pleasants)

“Don’t do that, Sissy,” Debbie implored. Then she said, “Tell my kids I’m sorry.”

“Debbie, you did the best you could.”

“Timmy is with me,” Debbie resolved.

At that moment, Glenda realized her sister knew that death was inevitable. Toward the end of their conversation, Debbie asked Glenda to help her file for medical clemency with the parole board. “We’ll get you home,” Glenda promised.

In the following weeks, doctors moved Debbie into a wheelchair. Once, Debbie declined a shuttle ride to the hospital. “My body needs a break,” she wrote on her refuse-to-consent form. On another occasion, a Fluvanna doctor brought Debbie a Do Not Resuscitate form, she wrote to Glenda. He told her to go ahead and sign because she had “the cancer” and it would only get worse.

That November, Debbie appeared in front of a video camera inside a small Fluvanna conference room to give a deposition. As guards wheeled her in, Castañeda joined a Legal Aid colleague and an assistant attorney general representing the state sat waiting. Castañeda was less than a month from trial, and Debbie’s testimony, she knew, was crucial. Even in the best-case scenario, it was possible Debbie would not be well enough to take the witness stand.

Debbie gently rocked back and forth in pain, noting that Fluvanna failed to give her morphine on several occasions that week. “I feel that the medical attention here is not appropriate,” she said, her voice soft and frank. “I realize people are in here for something they’ve done. But … to sit in pain and suffer twenty-four-seven is not fair, not for nobody. I know it’s not going to do much for me because I’m not going to be around. But maybe it will help somebody in the future.”

Less than three weeks later, on the eve of trial, the attorney general’s office agreed to settle with the Fluvanna inmates. Under the terms, which were formalized through a judge’s order last year, the Department of Corrections agreed to update its operating procedures regarding grievances, and allowed for an independent compliance monitor—a former chief medical officer at the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections—to make regular prison inspections and interview inmates for three years. (The assistant attorney general’s office, representing the Virginia Department of Corrections in this case, declined to comment for this story, claiming the matter remains “open” as Fluvanna remains under independent monitoring. Harold Clarke, the director of the Virginia Department of Corrections, also declined to be interviewed.)

Shortly after the settlement agreement, with the aid of Ramsdale and Castañeda, Debbie was given medical clemency. “I find it really sweet and unusual for a MD to want to help someone like she is trying to help me,” Debbie told Glenda, referring to Ramsdale. Debbie returned home to Richmond just in time for Thanksgiving, moving in with Glenda under hospice care. She quickly reconciled with her daughters, one of whom visited each day to care for her. Debbie’s grandchildren marched into her room with pictures they had drawn. A few arrived with their foster parents. “Everything she did was to make her children and grandchildren happy,” recalls Debbie’s daughter Kristine Hughes.

Only Glenda was permitted to bathe Debbie. As she dressed her sister, it seemed as if Glenda could count every bone in her body. Every morning, Glenda changed and cleaned Debbie’s colonoscopy bag. Sometimes they joked about the smell. Other times Glenda would weep. “You’re disappearing right in front of me and I can’t stop it,” Glenda said. “Don’t cry, Sissy,” Debbie said. “I’ll be OK.”

Glenda and Debbie had lost several people in their lives: Their mother left them; Debbie’s brother died as an infant; Timmy died at 20; each of their marriages failed. But, to Glenda, Debbie never faltered. She was home, Glenda thought, contemplating her sister’s final year: the medication lapses. The strip-searches. The isolation in the infirmary. Could that be torture? Glenda wondered.

By Christmas, Debbie’s skin seemed translucent. That month, Ramsdale gave birth to a son, and sent Glenda pictures. After moving her practice to upstate New York, Ramsdale placed a photo of Debbie and Timmy on a bookshelf by her desk, next to a picture of her own little boy, serving as a reminder that physicians have the power to advocate for their patients. Calling Debbie “remarkable,” Ramsdale says, “She did not deserve what happened to her.”

One night in March of 2015, Glenda asked if Debbie had felt Timmy’s presence since her return to Richmond. Debbie said she had not. “Will you tell me if you do?” Glenda asked. Debbie said she would.

The following morning, Glenda went to the kitchen fetch her sister a glass of water. As she walked back up the stairs, she noticed Debbie’s TV was not on like it normally was. She had died in the middle of the night, at 49.

Debbie did not want a funeral, so the family held a candlelit vigil. Glenda placed her sister’s ashes in an urn, and set it next to Timmy’s.

In one of her last prison letters to Glenda, Debbie wrote that she was on a mostly liquid diet, and worried she had lost too much weight.

Even then, Debbie was resolved to gain it back. Her entire life had been one of survival, and she was determined to persevere one last time.

“I can’t fight this if I’m not strong enuf to fight it,” she wrote. “And I’m not going down w/out a fight.”