Everyone aboard the Michael was there for one reason: They were going to vote in the Brazilian presidential election. It was early morning, and the passengers streamed up the wobbly gangplank and onto the boat docked at the chaotic port in Santarem, smack in the middle of the Amazon. They carried with them big duffel bags and babies, and families jostled through the crowd to reach the most desirable spots and hang up their hammocks. Enterprising vendors boarded as well, shouting offers of three-for-one pastries and ice-cold water, adding their enthusiastic weight to the sway of the rocking boat. The Michael is one of the oldest boats to dock at Santarem; its sky blue paint had chipped away many trips ago, and the wooden floor of its top deck was riddled with splintery cracks and rusty exposed nails. The bathroom—it was likely what you’re imagining.

But none of the other passengers overloading the boat seemed fazed by the conditions, and, unlike me, none of them seemed daunted when we set out onto the wide river finally. It was close to 100 degrees, and we were facing nine hours on a rickety boat full of crying children, far from cell signal or signs of industrialized civilization. I couldn’t believe that people were taking this hot, long, uncomfortable voyage just to vote in the election. The captain turned up the volume on his cheesy Brazilian soundtrack, adding a background thump to the human racket. It was going to be a long nine hours.

If you’ve followed any recent news from Brazil, you’ve heard about the all-important election coming up this weekend. The stakes are high: If the polls are right, Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right, homophobic demagogue will become leader of the world’s fourth-largest democracy. As Bolsonaro’s polling figures have risen, his campaigning style has become cocksure, and he expounds an alarming vision, one in which the government does away with the “coddling” of blacks and gays and women and “banishes” leftists from Brazil. The only man who can stop Bolsonaro is former São Paulo Mayor Fernando Haddad, a political stand-in for ex-president and leftist rabble-rouser Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who has been jailed for corruption.

But Haddad’s party, the Worker’s Party, has failed to confound the mythos that Bolsonaro has created for himself as an anti-corruption warrior. The result is a battle between two starkly visions for Brazil’s future.

What hasn’t made the news, though, is a portrait of a different Brazil from the one seen at the protests in Rio de Janeiro or the political rallies in São Paulo. It’s a Brazil that even most Brazilians don’t know, one that takes hours to reach by boat. In the village of São Pedro, deep in the Amazon, along the banks of the Arapiuns River, life could hardly be more removed from life in the cities. It’s a place where there’s no Wi-Fi and no real economy, a place where the dominant sound, besides the river, is the loud roar of the generator in the town square. But these citizens’ votes will count just as much as the votes in the big cities—and here, some communities’ long-term survival could be directly threatened by a Bolsonaro victory.

So that’s where I headed, for the first round of the election, on a trip that would reveal the contours of the place, and the country, in ways I could not have foreseen.

São Pedro is one of thousands of riverside villages throughout the Amazon region whose residents—called ribeirinhos, or, roughly, riverside folk—are only vaguely connected to the rest of Brazil. Saude e Alegria, a non-profit organization that monitors riverside communities in the Amazon, estimates that, in the four municipalities the group studies in the western part of the state of Pará, 70,000 people live in 250 ribeirinho communities. The curving Arapiuns River, on which São Pedro lies, hosts 68 communities along its banks; São Pedro, home to about 200 families, is one of the largest. Most of the other communities along the river are smaller, populated by not more than a few hundred people. The lives of these ribeirinhos, their struggles and hopes, represent some of the most overlooked stories in all of Brazil.

(Photo: Shannon Sims)

Part of why ribeirinhos are so easily overlooked by both government and media is because they don’t fit into simple categories. Their narratives are complex, and even determining the ethnic identity of ribeirinhos is a challenge. Some ribeirinhos identify as indigenous; some don’t. Some speak Portuguese, some don’t. The only commonality is that all of them are, by almost any standard, very poor.

The forefathers of many of the Brazilians living in the ribeirinho communities in this part of the Amazon moved here during the rubber boom, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, when latex drove the northern Brazilian economy and Henry Ford made his millions, establishing his Fordlandia outpost in the jungle to better access the rubber trees. The laborers during the boom made improvised homes along the banks of the rivers that braid into the Amazon. Once the industry went bust, many of the rubber workers moved to coastal cities; the ribeirinhos were the ones who stayed. Some of the communities they formed are nestled deep within the river forests and can only be reached by motorized canoes. Political campaigning here is done by boat, or water-bike.

São Pedro, in fact, is one of the few ribeirinho communities directly accessible by the iconic double-decker boats that look like colorful toys and function like Amazonian buses: They make stops at all the riverside communities along a route, picking up and dropping off passengers, and bringing supplies and messages (the communities are often far out of any cell-phone signal range, so messages are sent by word of mouth). On the boats, many of the passengers already know each other; they’re neighbors or family, or they’ve met on the boat route before.

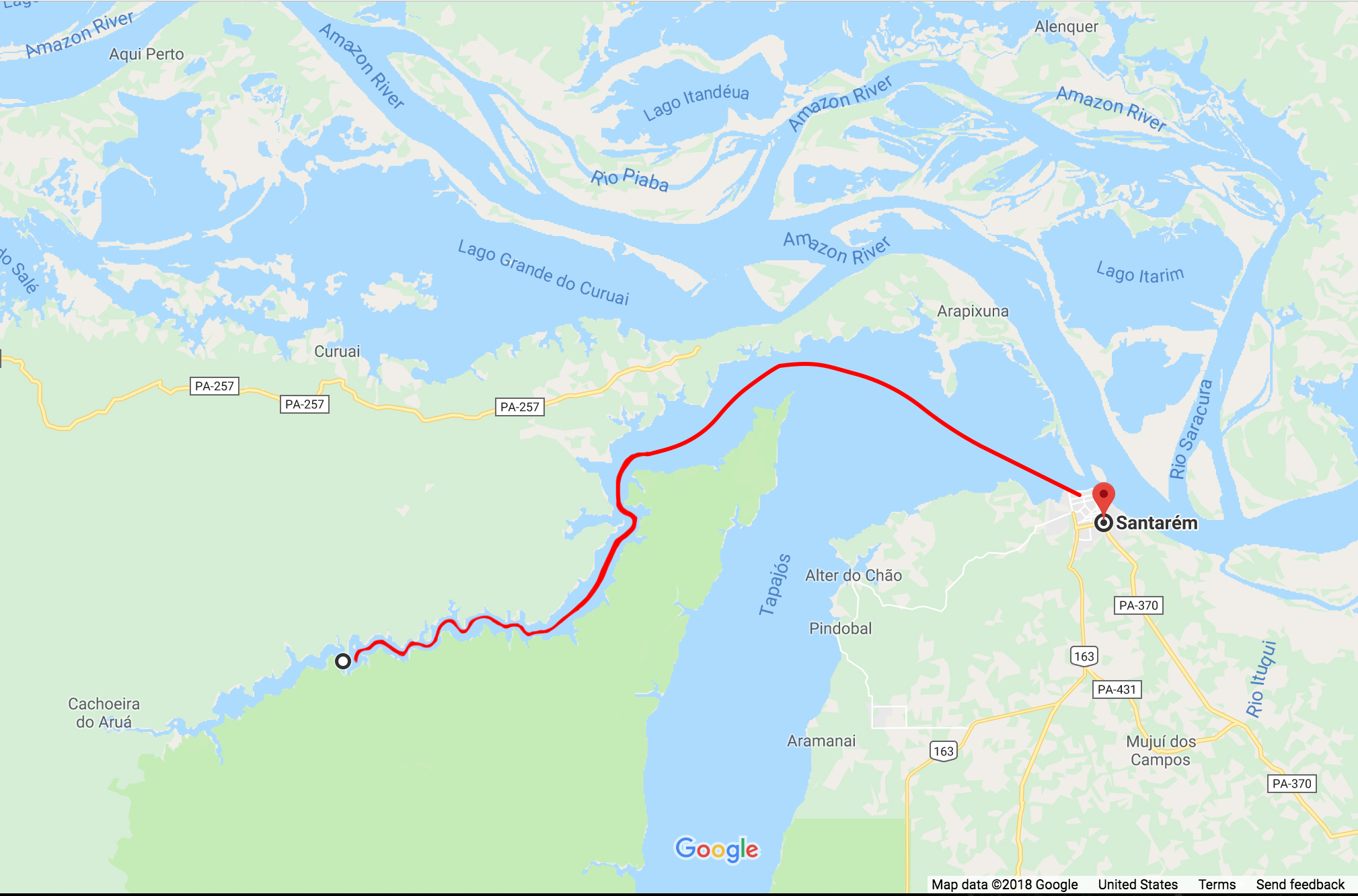

(Map: Emma Sarappo/Google)

These passenger boats, some of which journey for multiple days to reach ribeirinho communities isolated in the forest, become temporary residences for the passengers through all those hours of swaying, as the boat slowly makes its way upriver. They sleep beside one another in hammocks, swinging into each other when the waters get rough. On the boat’s one table near the bathroom, they play dominoes when even the hammocks get too sweaty in the afternoon heat. They cook lunch and dinners together, communal meals of rice and beans that are evenly portioned out so that everyone eats at once. At the different riverside stops, the men help unload supplies, while the women care for each other’s babies. These boats are at once public and intimate. They lack the amenities of modern life, but they also feel like a sanctuary from workaday routines; the most popular activity onboard is simply staring out at the forest as it passes by, hour by slow hour. Being on one of these boats is like being in a place that seems to float outside of Brazil, away from the difficulties that you find once the boat lands in the sands of the ribeirinho villages.

I wanted to see what the election was like for people who live in this overlooked Brazil. So I boarded the Michael, hooked up my dark green hammock, and joined the crowded ride upriver, into the belly of the Amazon.

In the United States, it sometimes makes the news if people have to stand for more than an hour to vote. But it didn’t seem so inconvenient or strange to the people on the Michael that they were having to commute nine hours in order to vote. In a way, they’re used to it. Because the ribeirinho communities have no real economies to speak of, many ribeirinhos today live a life in transition: Many say they moved to the city to work or study, but their voting residence is still back home in the ribeirinho community. Others still live in the ribeirinho village and take the Michael nine hours twice a week just to go to university or work for a day. Time ticks by slowly on the boat, but the passengers seem altogether unruffled by the commute.

(Photo: Shannon Sims)

And voting in Brazil is mandatory. If you don’t vote, and haven’t obtained prior permission to skip the election, you face a cascade of problems: You get flagged across government systems, and paying taxes or even buying a microwave becomes complicated. But voting also doesn’t seem like such an inconvenience when everyone is doing it. Election day is always Sunday, and so if you’re not standing in line to vote on that day, you’re out of the loop. As in the U.S., Brazilians are registered in their local municipalities, and so they must return to those locations on election day—even if it takes them 18 hours round-trip to do so.

By the time we embarked out of Santarem, the Michael was packed. A baby had been slung inside a hammock above me, a man was sleeping in a hammock below me, and the floor of the boat had no room to step between the coolers and duffel bags containing the city hauls of the passengers. I was on the upper level of the double-decker, where a hard breeze off the river kept us cool. But the floor below was dark and hot, and full of people.

In this year’s Brazilian election, protections for the Amazon rainforest are on the chopping block. Bolsonaro, the man almost certain to win, is floating proposals that terrify environmental advocates and supporters of indigenous land rights in Brazil. Bolsonaro has vowed to do away with the legislation that creates indigenous territories, the essential land rights tool for indigenous communities in the Amazon and a proxy for preventing deforestation. He’s also promised to open indigenous lands to mining.

São Pedro has always been a hotspot for the conflict over indigenous land rights. Years ago, the people here rallied together and set fire to the barges that were running illegally cut logs out of the forest. If Bolsonaro wins, São Pedro could see a real uptick in the pressure on its surrounding forests.

Today, São Pedro is one of many poor villages along the river, communities so poor that they’ve been called “Amazonian favelas.” In the village, bread is a luxury. “There used to be a bakery,” Marguereth told me with a shrug. Marguereth and her husband Livaldo Sarmento would be my hosts in São Pedro, and as we rode the Michael together, they told me about how things used to be in the town. Livaldo had been one of the community leaders who fought back against the loggers decades ago. Now, he was headed home to vote.

As we arrived in São Pedro—a spit of sand jutting out into the Arapiuns River in a way that forces the boats to curve at almost a right angle to keep along the river—I realized I’d been sleeping quite a lot. The warmth of the boat, the cradle of the hammock, and the steady sway of the water had knocked me out for much of the voyage to São Pedro. But now, upon arrival, I was still tired. Margareth showed me to a dark room in her home, without a door or much more than hammock hooks, to which she tied my green hammock. I slept 12 hours that night, even though a block away there was a barbecue party hosted by the local politician, in an effort to drum up last-minute support, blaring country music all night long.

By the morning, I felt feverish, and Margareth moved my hammock outside into the yard so I could get fresh air. Livaldo sat on a piece of wood next to me and watched me. I realized he was frightened for my health.

Before I had left Santarem and embarked toward São Pedro, I’d asked my local contact about what I should do if I got sick or hurt while in São Pedro. “There’s a posto de saude there” (a health clinic), he’d told me. “And in case of emergency, you can take an ambulancha“—the local nickname for a boat ambulance—”and it can get you back to the city in two and a half hours.”

I remembered that conversation when I saw Livaldo’s worried face. I asked him where the health clinic was; I thought I should probably be seen by a doctor. “The health clinic?” he asked, visibly surprised. Margareth chimed in. “There’s no doctor here. There’s only a nurse. But she’s in the city. And she’s only here one day a week. On Wednesdays.” It was Friday.

Margareth told me I wouldn’t want to go to the clinic, even if the nurse was in town. A while ago, she said, the government claimed that it had been sending resources out to the health clinic. “But we never saw them. We never got any medicines or vaccinations,” she said, visibly disgusted, and went on to explain that, in response, the community had gathered together and broken into the clinic’s back room.

“We found hundreds of medications piled up there, all expired,” she said. “They’d been expired for years!” I felt a warm wave come over my face and sensed incoming panic. I took a deep breath.

“OK, well what about the ambulancha?” I asked. “Could I take that?”

Margareth laughed in response. “That hasn’t worked for three years.” I closed my eyes, took a few more deep breaths, and fell back asleep.

That’s right around when the dog started talking to me.

“Hot, right?” he asked. I agreed that it was, indeed, quite hot. He’d been dying beneath me for a while, seemingly forever. His hind hipbones were raw and red and exposed to the flies. I fell asleep while he was mid-sentence and felt a bit bad about it, but I was just too tired.

I woke up as Marguereth offered me a plate of bruised yellow cashew fruit. “You need to eat,” she said, and handed me the plate before leaving again. I tried to eat the cashew fruit, but couldn’t, so I tossed the rest of the fruit to the dog, who ate it up in a second. The dog then sat back, as if to smoke a pipe, and adjusted his spectacles. “Those frame your face really well,” I told him. “Thank you,” he said with a smile. A short while later, a helicopter made a slow landing in my hammock. I moved my legs a bit to the side, so they wouldn’t be cut by the propellers.

When I woke up, I was soaking wet. Marguereth touched me and said I felt like ice and insisted that I eat the fish broth she had cooked by boiling the local charutinho fish in water with a few bits of tomato, onion, and cilantro. I told her I didn’t think I could eat fish—the thought of it made me faint—so she offered me something else, in a white plastic bag. It was heavy and pokey. When I opened the bag, the nails on a foot scratched my hand. A beige shell covered in shiny hexagons had black grill marks on it, and there was no head; it appeared to be just the hindquarters of something, about the size of a volleyball. I pulled off some of the white meat inside the shell. It came off like Thanksgiving turkey breast, and tasted like it too. It was endangered armadillo.

“I think you should leave on the next boat,” Livaldo declared. He told me later with a kind of morbid humor that he had been worried about having a dead gringa on his hands. Coincidentally, the next boat to leave was the Michael, and it was scheduled to depart São Pedro halfway through election day, making stops along the Arapiuns on its route back to Santarem, picking up voters who wanted to get back to the city in time for work the next morning. Livaldo helped me string up my hammock on the upper deck of the Michael, and then sent me off with a three-gallon bottle of water, some biscuits, and a nervous wave from the shore.

When I would finally make it back to the mainland and to the public hospital many, many hours later, a new sort of delusional nightmare began. Several people in the waiting room of the Municipal Hospital of Santarem were missing limbs. Skinny elderly people were draped across chairs, sleeping or dying. A man with a gash down his back and burn marks—the results of a motorcycle accident, I guessed—bumped against me as he walked into the nurse’s office. I went to the bathroom to wash his blood off my arm, but the door was locked. A woman waiting outside of it spit on the ground in front of me. It was a hot room full of human need.

(Photo: Shannon Sims)

By the time I made it to the doctor, hours later, she told me my diagnosis was one of four options: malaria, dengue, chikunguya, or Zika. I was sent to the lab to get my blood drawn, and as the needle went into my arm, I was suddenly nauseous. The exasperated nurse handed me a trash can half-full with someone else’s orange vomit. Hours later, my malaria test came back negative. The result was communicated via a handwritten note, with my name very misspelled, and the birthdate of a 21-year-old in place of my own.

The people of São Pedro travel nine hours by boat for these health services—just as they do to vote.

When I set out on this assignment, I didn’t anticipate getting so sick, but the experience sent me into the depths of what life is really like for the riverside people in the Amazon; I saw their lives in a way I never would have had I remained healthy. At various points during my illness, I would awake in a sweat with a wave of anxiety and dark thoughts rolling over me: Am I going to die here? I wondered many times as I lay in my hammock in São Pedro, too weak to be able to seek out help. Death lurked in the corners of my mind like a shadow on a hot afternoon, and with it came a kind of primal fear, one that is regular in these communities, where help is so many hours away. During my time there, the community was abuzz with worry about a 14-year-old girl who had given birth a week earlier and now seemed in poor health, having lost all feeling in one leg.

Even before the Michael pushed off from the sands of São Pedro, and before I made it all the way to the hospital, I summoned the strength to roam my way around the wooden deck of the Michael to ask my fellow passengers which presidential candidate they’d voted for that morning. Most had voted for the leftist Fernando Haddad, but there were some exceptions.

Messias Gama dos Santos is a 20-year-old from São Joao, a community of 25 families up the Arapiuns River. He told me he had cast his presidential ballot for the former governor of São Paulo, Geraldo Alckmin, the man who—with his fancy suit and career of catering to the pro-business wealthy—seemed like the least likely candidate to get dos Santos’ vote. But dos Santos said that he saw Alckmin as “capable”: “He did good things in São Paulo, and so he could be the one to get Brazil out of this situation.” Not enough Brazilians agreed with him: Alckmin ended up being knocked out in the first round of voting.

Dos Santos was also in the minority on the vote boat: He was the only voter I encountered on the Michael in either direction who admitted to voting for anyone other than Haddad. In fact, in the first round of voting, in Pará state, Haddad ended up with 41 percent of the vote, beating Bolsonaro’s 36 percent; in most of Brazil, though, Haddad had fewer votes than Bolsonaro.

The reason has a lot to do with economics. Most of the people on the boat voluntarily offered to me that they identified as “poor” or “very poor,” and said they saw Haddad as the best defender of poor people like them.

That’s the case for Maria Aparecida de Aquino, a schoolteacher who takes the boat twice a month so she can restock supplies for her students. “I think Haddad is a supporter of the poorest people,” Aquino said, adding that she was voting for Haddad also because she was frightened by the way Bolsonaro seemed to endorse violence in his campaign, with calls for increased gun ownership and overtures to military rule.

The boat’s captain, 31-year-old Robson Souza, lives in a riverside settlement of the Landless Workers’ Movement, a land-rights movement that thrived in the 1980s in Brazil and that still drives the politics of many rural voters across the country. The settlement where Souza lives, called Bom Futuro, or “Good Future,” was one of about 10 stops the Michael made on the way back to Santarem from São Pedro. We waited on the boat as Souza ran up the banks of the river to vote and then, 15 minutes later, ran back. He’d cast his ballot for Haddad.

“I think Bolsonaro will end the welfare program, and I think he won’t let us live in the settlement anymore,” Souza said. Even though Souza said he was not on welfare, thanks to the boat job, he said he had family members who were. He added: “I think he would end up being the worst president in the history of Brazil.”

And then there was Zica Lopes Ferreira, who goes by Diva. The 59-year-old resident of São Pedro twisted her mouth and anxiously breathed in through her nose when I asked her who she had voted for. “Look,” she said. “I’m going to be sincere with you.” She fiddled with a stray domino on the boat’s table. “I didn’t know which numbers to press,” she said, “so I just guessed.”

Years ago, Brazil moved to a system of assigning numbers to each candidate, as a way of allowing people who were illiterate and unable to read the names to still be able to vote. But Diva’s level of electoral literacy is so elementary, that even the numbers assigned to the candidates got scrambled for her. After taking the boat nine hours to the voting station, she ended up pushing random numbers just to get out of the voting booth.

Diva looked at me sheepishly as she told me this, but her answer broke my heart. Here was this woman, way out in the middle of the Arapiuns River, on this creaky old boat Michael, on her way to places that most people would describe as “nowhere,” and she was still trying to somehow play a part in this national election with global consequences.

“I would have voted for Haddad,” Diva continued, looking across at the riverbank drifting by. “I think he would offer a lot to the riverside people. The ribeirinhos could use the help.”