The office looks like the aftermath of a surrealistic earthquake, as if David Cope’s brain has spewed out decades of memories all over the carpet, the door, the walls, even the ceiling. Books and papers, music scores and magazines are all strewn about in ragged piles. A semi-functional Apple Power Mac 7500 (discontinued April 1, 1996) sits in the corner, its lemon-lime monitor buzzing. Drawings filled with concepts for a never-constructed musical-radio-space telescope dominate half of one wall. Russian dolls and an exercise bike, not to mention random pieces from homemade board games, peek out from the intellectual rubble. Above, something like 200 sets of wind chimes from around the world hang, ringing oddly congruent melodies.

And in the center, the old University of California, Santa Cruz, emeritus professor reclines in his desk chair, black socks pulled up over his pants cuffs, a thin mustache and thick beard lending him the look of an Amish grandfather.

It was here, half a dozen years ago, that Cope put Emmy to sleep. She was just a software program, a jumble of code he’d originally dubbed Experiments in Musical Intelligence (EMI, hence “Emmy”). Still — though Cope struggles not to anthropomorphize her — he speaks of Emmy wistfully, as if she were a deceased child.

Emmy was once the world’s most advanced artificially intelligent composer, and because he’d managed to breathe a sort of life into her, he became a modern-day musical Dr. Frankenstein. She produced thousands of scores in the style of classical heavyweights, scores so impressive that classical music scholars failed to identify them as computer-created. Cope attracted praise from musicians and computer scientists, but his creation raised troubling questions: If a machine could write a Mozart sonata every bit as good as the originals, then what was so special about Mozart? And was there really any soul behind the great works, or were Beethoven and his ilk just clever mathematical manipulators of notes?

Cope’s answers — not much, and yes — made some people very angry. He was so often criticized for these views that colleagues nicknamed him “The Tin Man,” after the Wizard of Oz character without a heart. For a time, such condemnation fueled his creativity, but eventually, after years of hemming and hawing, Cope dragged Emmy into the trash folder.

This month, he is scheduled to unveil the results of a successor effort that’s already generating the controversy and high expectations that Emmy once drew. Dubbed “Emily Howell,” the daughter program aims to do what many said Emmy couldn’t: create original, modern music. Its compositions are innovative, unique and — according to some in the small community of listeners who’ve heard them performed live — superb.

Sample of Emily Howell — Track 1

Click here to listen without Quicktime

Sample of Emily Howell — Track 2

Click here to listen without Quicktime

With Emily Howell, Cope is, once again, challenging the assumptions of artists and philosophers, exposing revered composers as unknowing plagiarists and opening the door to a world of creative machines good enough to compete with human artists. But even Cope still wonders whether his decades of innovative, thought-provoking research have brought him any closer to his ultimate goal: composing an immortal, life-changing piece of music.

Cope’s earliest memory is looking up at the underside of a grand piano as his mother played. He began lessons at the age of 2, eventually picking up the cello and a range of other instruments, even building a few himself. The Cope family often played “the game” — his mother would put on a classical record, and the children would try to divine the period, the style, the composer and the name of works they’d read about but hadn’t heard. The music of masters like Rachmaninov and Stravinsky instilled in him a sense of awe and wonder.

Nothing, though, affected Cope like Tchaikovsky‘s Romeo and Juliet, which he first heard around age 12. Its unconventional chord changes and awesome Sturm und Drang sound gave him goose bumps. From then on, he had only one goal: writing a piece that some day, somewhere, would move some child the same way Tchaikovsky moved him. “That, just simply, was the orgasm of my life,” Cope says.

He begged his parents to pay for the score, brought it home and translated it to piano; he studied intensely and bought theory books, divining, scientifically, what made it work. It was then he knew he had to become a composer.

Cope sailed through music schooling at Arizona State University and the University of Southern California, and by the mid-1970s, he had settled into a tenured position at Miami University of Ohio’s prestigious music department. His compositions were performed in Carnegie Hall and The Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and internationally from Lima, Peru, to Bialystok, Poland. He built a notable electronic music studio and toured the country, wowing academics with demonstrations of the then-new synthesizer. He was among the foremost academic authorities on the experimental compositions of the 1960s, a period during which a fired-up jet engine and sounds derived from placing electrodes on plants were considered music.

When Cope moved to UC Santa Cruz in 1977 to take a position in its music department, he could’ve put his career on autopilot and been remembered as a composer and author. Instead, a brutal case of composer’s block sent him on a different path.

In 1980, Cope was commissioned to write an opera. At the time, he and his wife, Mary (also a Santa Cruz music faculty member), were supporting four children, and they’d quickly spent the commission money on household essentials like food and clothes. But no matter what he tried, the right notes just wouldn’t come. He felt he’d lost all ability to make aesthetic judgments. Terrified and desperate, Cope turned to computers.

Along with his work on synthesis, or using machines to create sounds, Cope had dabbled in the use of software to compose music. Inspired by the field of artificial intelligence, he thought there might be a way to create a virtual David Cope software to create new pieces in his style.

The effort fit into a long tradition of what would come to be called algorithmic composition. Algorithmic composers use a list of instructions — as opposed to sheer inspiration — to create their works. During the 18th century, Joseph Haydn and others created scores for a musical dice game called Musikalisches Würfelspiel, in which players rolled dice to determine which of 272 measures of music would be played in a certain order. More recently, 1950s-era University of Illinois researchers Lejaren Hiller and Leonard Isaacson programmed stylistic parameters into the Illiac computer to create the Illiac Suite, and Greek composer Iannis Xenakis used probability equations. Much of modern popular music is a sort of algorithm, with improvisation (think guitar solos) over the constraints of simple, prescribed chord structures.

Few of Cope’s major works, save a dalliance with Navajo-style compositions, had strayed far from classical music, so he wasn’t a likely candidate to rely on software to write. But he did have an engineer’s mind, composing using note-card outlines and a level of planning that’s rare among free-spirited musicians. He even claims to have created his first algorithmic composition in 1955, instigated by the singing of wind over guide wires on a radio tower.

Cope emptied Santa Cruz’s libraries of books on artificial intelligence, sat in on classes and slowly learned to program. He built simple rules-based software to replicate his own taste, but it didn’t take long before he realized the task was too difficult. He turned to a more realistic challenge: writing chorales (four-part vocal hymns) in the style of Johann Sebastian Bach, a childhood favorite. After a year’s work, his program could compose chorales at the level of a C-student college sophomore. It was correctly following the rules, smoothly connecting chords, but it lacked vibrancy. As AI software, it was a minor triumph. As a method of producing creative music, it was awful.

Cope wrestled with the problem for months, almost giving up several times. And then one day, on the way to the drug store, Cope remembered that Bach wasn’t a machine — once in a while, he broke his rules for the sake of aesthetics. The program didn’t break any rules; Cope hadn’t asked it to.

The best way to replicate Bach’s process was for the software to derive his rules — both the standard techniques and the behavior of breaking them. Cope spent months converting 300 Bach chorales into a database, note by note. Then he wrote a program that segmented the bits into digital objects and reassembled them the way Bach tended to put them together.

The results were a great improvement. Yet as Cope tested the recombinating software on Bach, he noticed that the music would often wander and lacked an overall logic. More important, the output seemed to be missing some ineffable essence.

Again, Cope hit the books, hoping to discover research into what that something was. For hundreds of years, musicologists had analyzed the rules of composition at a superficial level. Yet few had explored the details of musical style; their descriptions of terms like “dynamic,” for example, were so vague as to be unprogrammable. So Cope developed his own types of musical phenomena to capture each composer’s tendencies — for instance, how often a series of notes shows up, or how a series may signal a change in key. He also classified chords, phrases and entire sections of a piece based on his own grammar of musical storytelling and tension and release: statement, preparation, extension, antecedent, consequent. The system is analogous to examining the way a piece of writing functions. For example, a word may be a noun in preparation for a verb, within a sentence meant to be a declarative statement, within a paragraph that’s a consequent near the conclusion of a piece.

Finally, Cope’s program could divine what made Bach sound like Bach and create music in that style. It broke rules just as Bach had broken them, and made the result sound musical. It was as if the software had somehow captured Bach’s spirit — and it performed just as well in producing new Mozart compositions and Shakespeare sonnets. One afternoon, a few years after he’d begun work on Emmy, Cope clicked a button and went out for a sandwich, and she spit out 5,000 beautiful, artificial Bach chorales, work that would’ve taken him several lifetimes to produce by hand.

When Emmy’s Bach pieces were first performed, at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1987, they were met with stunned silence. Two years later, a series of performances at the Santa Cruz Baroque Festival was panned by a music critic — two weeks before the performance. When Cope played “the game” in front of an audience, asking which pieces were real Bach and which were Emmy-written Bach, most people couldn’t tell the difference. Many were angry; few understood the point of the exercise.

Cope tried to get Emmy a recording contract, but classical record companies said, “We don’t do contemporary music,” and contemporary record companies said the opposite. When he finally did land a deal, no musician would play the music. He had to record it with a Disklavier (a modern player piano), a process so taxing he nearly suffered a nervous breakdown.

Though musicians and composers were often skeptical, Cope soon attracted worldwide notice, especially from scientists interested in artificial intelligence and the small, promising field called artificial creativity. Other “AC” researchers have written programs that paint pictures; that tell Mexican folk tales or write detective novels; and that come up with funny jokes. They have varying goals, though most seek to better understand human creativity by modeling it in a machine.

To many in the AC community, including the University of Sussex’s Margaret Boden, doyenne of the field, Emmy was an incredible accomplishment. There’s a test, named for World War II-era British computer scientist Alan Turing, that’s a simple check for so-called artificial intelligence: whether or not a person interacting with a machine and a human can tell the difference. Given its success in “the game,” it could be argued that Emmy passed the Turing Test.

Cope had taken an unconventional approach. Many artificial creativity programs use a more sophisticated version of the method Cope first tried with Bach. It’s called intelligent misuse — they program sets of rules, and then let the computer introduce randomness. Cope, however, had stumbled upon a different way of understanding creativity.

In his view, all music — and, really, any creative pursuit — is largely based on previously created works. Call it standing on the shoulders of giants; call it plagiarism. Everything we create is just a product of recombination.

In Cope’s fascinating hovel of a home office on a Wednesday afternoon, I ask him how exactly he knows that’s true. Just because he built a program that can write music using his model, how can he be so certain that that’s the way man creates?

Cope offers a simple thought experiment: Put aside the idea that humans are spiritually and creatively endowed, because we’ll probably never fully be able to understand that. Just look at the zillions of pieces of music out there.

“Where are they going to come up with sounds that they themselves create without hearing them first?” he asks. “If they’re hearing them for the first time, what’s the author of them? Is it birds, is it airplane sounds?”

Of course, some composers probably have taken dictation from birds. Yet the most likely explanation, Cope believes, is that music comes from other works composers have heard, which they slice and dice subconsciously and piece together in novel ways. How else could a style like classical music last over three or four centuries?

To prove his point, Cope has even reverse-engineered works by famous composers, tracing the tropes, phrases and ideas back to compositions by their forebears.

“Nobody’s original,” Cope says. “We are what we eat, and in music, we are what we hear. What we do is look through history and listen to music. Everybody copies from everybody. The skill is in how large a fragment you choose to copy and how elegantly you can put them together.”

Cope’s claims, taken to their logical conclusions, disturb a lot of people. One of them is Douglas Hofstadter, a Pulitzer Prize-winning cognitive scientist at Indiana University and a reluctant champion of Cope’s work. As Hofstadter has recounted in dozens of lectures around the globe during the past two decades, Emmy really scares him.

Like many arts aficionados, Hofstadter views music as a fundamental way for humans to communicate profound emotional information. Machines, no matter how sophisticated their mathematical abilities, should not be able to possess that spiritual power. As he wrote in Virtual Music, an anthology of debates about Cope’s research, Hofstadter worries Emmy proves that “things that touch me at my deepest core — pieces of music most of all, which I have always taken as direct soul-to-soul messages — might be effectively produced by mechanisms thousands if not millions of times simpler than the intricate biological machinery that gives rise to a human soul.”

I ask Cope whether Emmy bothers him. This is a man who averages about four daily hours of hardcore music listening, who’s touched so deeply by a handful of notes on the piano as to shut his eyes in reverie.

“I can understand why it’s an issue if you’ve got an extremely romanticized view of what art is,” he says. “But Bach peed, and he shat, and he had a lot of kids. We’re all just people.”

As Cope sees it, Bach merely had an extraordinary ability to manipulate notes in a way that made people who heard his music have intense emotional reactions. He describes his sometimes flabbergasting conversations with Hofstadter: “I’d pull down a score and say, ‘Look at this. What’s on this page?’ And he’d say, ‘That’s Beethoven, that’s music of great spirit and great soul.’ And I’d say, ‘Wow, isn’t that incredible! To me, it’s a bunch of black dots and black lines on white paper! Where’s the soul in there?'”

Cope thinks the old cliché of beauty in the eye of the beholder explains the situation well: “The dots and lines on paper are merely triggers that set things off in our mind, do all the wonderful things that give us excitement and love of the music, and we falsely believe that somewhere in that music is the thing we’re feeling,” he says. “I don’t know what the hell ‘soul’ is. I don’t know that we have any of it. I’m looking to get off on life. And music gets me off a lot of the time. I really, really, really am moved by it. I don’t care who wrote it.”

He does, of course, see Emmy as a success. He just thinks of her as a tool. Everything Emmy created, she created because of software he devised. If Cope had infinite time, he could have written 5,000 Bach-style chorales. The program just did it much faster.

“All the computer is is just an extension of me,” Cope says. “They’re nothing but wonderfully organized shovels. I wouldn’t give credit to the shovel for digging the hole. Would you?”

Cope has a complex relationship with his critics, and with people like Hofstadter who are simultaneously awed and disturbed by his work. He denounces some as focused on the wrong issues. He describes others as racists, prejudiced against all music created by a computer. Yet he thrives on the controversy. If not for the harsh reaction to the early Bach chorales, Cope says, he probably would have abandoned the project. Instead, he decided to “ram Emmy down their throats,” recording five more albums of the software’s compositions, including an ambitious Rachmaninov concerto that nearly led to another nervous breakdown from lack of sleep and overwork.

For the next decade, he fed off the anger and confusion and kudos from colleagues and admirers. Years after the 1981 opera was to be completed, Cope fed a database of his own works into Emmy. The resulting score was performed to the best reviews of his life. Emmy’s principles of recombination and pattern recognition were adapted by architects and stock traders, and Cope experienced a brief burst of fame in the late 1990s, when The New York Times and a handful of other publications highlighted his work. Insights from Emmy percolated the literature of musical style and creativity — particularly Emmy’s proof-by-example that a common grammar and language underlie almost all music, from Asian to Western classical styles. Eleanor Selfridge-Field, senior researcher at Stanford University’s Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities, likens Cope’s discoveries to the findings from molecular biology that altered the field of biology.

“He has revealed a lot of essential elements of musical style, and the definition of musical works, and of individual contributions to the evolution of music, that simply haven’t been made evident by any other process,” she says. “That really is an important contribution to our understanding of music, revealing some things that are really worth knowing.”

Nevertheless, by 2004, Cope had received too many calls from well-known musicians who wanted to perform Emmy’s compositions but felt her works weren’t “special” enough. He’d produced more than 1,000 in the style of several composers, an endless spigot of material that rendered each one almost commonplace. He feared his Emmy work made him another Vivaldi, the famous composer often criticized for writing the same pieces over and over again. Cope, too, felt Emmy had cheated him out of years of productivity as a composer.

“I knew that, eventually, Emmy was going to have to die,” he says. During the course of weeks, Cope found every copy of the many databases that comprised Emmy and trashed them. He saved a slice of the data and the Emmy program itself, so he could demonstrate it for academic purposes, and he saved the scores she wrote, so others could play them. But he’d never use Emmy to write again. She was gone.

For years, Cope had been experimenting with a different kind of virtual composer. Instead of software based on re-creation, he hoped to build something with its own personality.

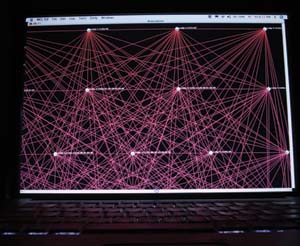

This program would write music in an odd sort of way. Instead of spitting out a full score, it converses with Cope through the keyboard and mouse. He asks it a musical question, feeding in some compositions or a musical phrase. The program responds with its own musical statement. He says “yes” or “no,” and he’ll send it more information and then look at the output. The program builds what’s called an association network — certain musical statements and relationships between notes are weighted as “good,” others as “bad.” Eventually, the exchange produces a score, either in sections or as one long piece.

Most of the scores Cope fed in came from Emmy, the once-removed music from history’s great composers. The results, however, sound nothing like Emmy or her forebears. “If you stick Mozart with Joplin, they’re both tonal, but the output,” Cope says, “is going to sound like something rather different.”

Because the software was Emmy’s “daughter” — and because he wanted to mess with his detractors — Cope gave it the human-sounding name Emily Howell. With Cope’s help, Emily Howell has written three original opuses of varying length and style, with another trio in development. Although the first recordings won’t be released until February, reactions to live performances and rough cuts have been mixed. One listener compared an Emily Howell work to Stravinsky; others (most of whom have heard only short excerpts online) continue to attack the very idea of computer composition, with fierce debates breaking out in Internet forums around the world.

At one Santa Cruz concert, the program notes neglected to mention that Emily Howell wasn’t a human being, and a chemistry professor and music aficionado in the audience described the performance of a Howell composition as one of the most moving experiences of his musical life. Six months later, when the same professor attended a lecture of Cope’s on Emily Howell and heard the same concert played from a recording, Cope remembers him saying, “You know, that’s pretty music, but I could tell absolutely, immediately that it was computer-composed. There’s no heart or soul or depth to the piece.”

That sentiment — present in many recent articles, blog posts and comments about Emily Howell — frustrates Cope. “Most of what I’ve heard [and read] is the same old crap,” he complains. “It’s all about machines versus humans, and ‘aren’t you taking away the last little thing we have left that we can call unique to human beings — creativity?’ I just find this so laborious and uncreative.”

Emily Howell isn’t stealing creativity from people, he says. It’s just expressing itself. Cope claims it produced musical ideas he never would have thought about. He’s now convinced that, in many ways, machines can be more creative than people. They’re able to introduce random notions and reassemble old elements in new ways, without any of the hang-ups or preconceptions of humanity.

“We are so damned biased, even those of us who spend all our lives attempting not to be biased. Just the mere fact that when we like the taste of something, we tend to eat it more than we should. We have our physical body telling us things, and we can’t intellectually govern it the way we’d like to,” he says.

In other words, humans are more robotic than machines. “The question,” Cope says, “isn’t whether computers have a soul, but whether humans have a soul.”

Cope hopes such queries will attract more composers to give his research another chance. “One of the criticisms composers had of Emmy was: Why the hell was I doing it? What’s the point of creating more music, supposedly in the style of composers who are dead? They couldn’t understand why I was wasting my time doing this,” Cope says.

That’s already changed.

“They’re seeing this now as competition for themselves. They see it as, ‘These works are now in a style we can identify as current, as something that is serious and unique and possibly competitive to our own work,'” Cope says. “If you can compose works fast that are good and that the audience likes, then this is something.”

I ask Cope whether he’s actually heard well-known composers say they feel threatened by Emily Howell.

“Not yet,” he tells me. “The record hasn’t come out.”

The following afternoon, we walk into Cope’s campus office, which seems like another college dorm room/psychic dump, with stacks of compact discs and scores growing from the floor like stalagmites, and empty plastic juice bottles scattered about. The one thing that looks brand-new is the black upright piano against the near wall.

Cope pulls up a chair, removes his Indiana Jones hat and eagerly explains the latest phase of his explorations into musical intelligence. Though he’s still poking around with Emily Howell, he’s now spending the bulk of his composition time employing on-the-fly programs.

Here’s how this cyborg-esque composing technique works: Cope comes up with an idea. For instance, he’ll want to have five voices, each of which alternates singing groups of four notes. Or perhaps he’ll want to write a piece that moves quickly from the bottom of the piano keyboard to the top, and then back down. He’ll rapidly code a program to create a chunk of music that follows those directions.

After working with Emmy and Emily Howell for nearly 30 years and composing for about twice that many, Cope is fast enough to hear something in his head in the bathtub, dry off and get dressed, move to the computer and 10 minutes later have a whole movement of 100 measures ready. It may not be any good, but it’s the fastest way to translate his thoughts into a solid rough draft.

“I listen with creative ears, and I hear the music that I want to hear and say, ‘You know? That’s going to be fabulous,’ or ‘You know … ‘” — he makes a spitting noise — “‘in the toilet.’ And I haven’t lost much, even though I’ve got a whole piece that’s in notation immediately.”

He compares the process to a sculptor who chops raw shapes out of a block of marble before he teases out the details. Using quick-and-dirty programs as an extension of his brain has made him extraordinarily prolific. It’s a process close to what he was hoping for back when he first started working on software to save him from composer’s block.

As complex as Cope’s current method is, he believes it heralds the future of a new kind of musical creation: armies of computers composing (or helping people compose) original scores.

“I think it’s going to happen,” Cope says. “I don’t believe that composers are stupid people. Ultimately, they’re going to use any tool at their disposal to get what they’re after, which is, after all, good music they themselves like to listen to. There will be initial withdrawal, but eventually it’s going to happen — whether we want it to or not.”

Already, at least one prominent pop group — he’s signed a confidentiality agreement, so he can’t say which one — asked him to use software to help them write new songs. He also points to services like Pandora, which uses algorithms to suggest new music to listeners.

If Cope’s vision does come true, it won’t be due to any publicity efforts on his part. He’ll answer questions from anyone, but he refuses to proactively promote his ideas. He still hasn’t told most of his colleagues or close friends about Tinman, a memoir he clandestinely published last year. The attitude, which he settled on at a young age, is to “treat myself as if I’m dead,” so he won’t affect how his work is received. “If you have to promote it to get people to like it,” he asks, “then what have you really achieved?”

Cope has sold tens of thousands of books, had his works performed in prestigious venues and taught many students who evangelize his ideas around the world. Yet he doesn’t think it adds up to much. All he ever wanted was to write something truly wonderful, and he doesn’t think that’s happened yet. As a composer, Cope laments, he remains a “frustrated loser,” confused by the fact that he burned so much time on a project that stole him away from composing. He still just wants to create that one piece that changes someone’s life — it doesn’t matter whether it’s composed by one of his programs, or in collaboration with a machine, or with pencil on a sheet of paper.

“I want that little boy or girl to have access to my music so they can play it and get the same thrill I got when I was a kid,” he says. “And if that isn’t gonna happen, then I’ve completely failed.”