5:00 A.M.

“Waking up is the hardest thing,” Joe says, finishing a cigarette in the back parking lot of a truck stop in Caddo Valley, Arkansas. Joe is in his mid-40s, and has driven a truck for 14 years. He’s in the middle of a run from Dallas, where he lives, to Nashville, Tennessee, though his range includes the entire continental United States. He’s almost always in the middle of going somewhere.

His freight might consist of anything, but lately has mostly been water. Forty-five thousand pounds of water. A little while ago, Joe had woken up and taken advantage of his complimentary shower—the truck stop offers showers for every 50 gallons of diesel pumped—when he realized he’d locked his keys in the cab of his truck. That’s why he’s wearing gym shorts and flip flops, his hair tousled and wet, smoking outside in the cold while he waits for dispatch to send help. “Getting up in the morning, starting your day,” he says, “it sucks.”

I’m only here to observe. Truck stops are fascinating, composite places, at once dense and secluded. They’re one-stop shops that are also offices, restaurants, public facilities, and homes. I’m here, maybe unwisely, to see what happens to one of them over the course of 24 hours. The idea is to get a sense of the whole equation, of what these spaces mean to people, how they are used, and how they change over time.

In front of us, long rows of tractor-trailers are tucked away for the night, many of their engines left idling for heat. It’s still dark outside, save a few headlights and the red and green glow of the gas station sign. It’s strange to consider that almost every truck in the lot, and there are around 50 of them, contains a driver currently asleep in the narrow berth behind the cab’s front seats. There are legal, as well as practical reasons for this: The Department of Transportation insists on 11 consecutive hours of rest for every 14 hours on duty. There aren’t many places where semi-trucks are welcome overnight, but they are always welcome here.

Joe tells me he’ll probably drive for another year and then stop for good. “One more year and I’ll be out,” he says, sounding like a bank robber in a heist movie. He’s tired of “fighting traffic and finding a place to park at night.” The money is good, but “everybody really keeps to themselves.” It’s lonely. He has a family, and wants to find work that would let him stay in Dallas. He’s never home as it is. “In the beginning you love doing it,” he says, trailing off.

8: 30 A.M.

Caddo Valley is a small strip of about three square miles off Interstate 30 in the southwest quadrant of the state. It claims a population of 635. This is deep pine country, with thick green and yellow forests stretching out in all directions. Highway 7 runs through the center of town. It is the town, more or less: a small cluster of gas stations, flea markets, and rustic antique stores. Hand-painted signs advertise inner-tube rentals and a nearby bar called The Mirage. This segment of the road was years ago officially designated the “Highway of Hope,” because it was so frequently part of Bill Clinton’s route to his hometown, Hope, which is 50 miles away.

The sun rises over a Holiday Inn billboard at the back of the lot, and the herd of trucks begins to thin, as drivers wake up, fill huge thermoses of coffee, grab breakfast, and head back out on the road. This particular stop belongs to the Pilot Flying J chain, the largest truck stop operation in the U.S. A dozen gasoline lanes service everyday cars and trucks in the front, while the big rigs go around to the back of the building, through eight crowded diesel lanes that are collectively referred to as “Fuel Island.”

These two populations, the everyday drivers and the truckers, overlap but rarely interact inside the truck stop itself, a convenience store and 24-hour diner featuring a standalone Cinnabon. It’s easy enough to tell the groups apart. The truckers are the ones brushing their teeth in the bathroom sink, and lugging duffel bags of laundry across the lot. They seem unnaturally calm and generally exhausted, staring straight ahead at nothing in particular. They are as diverse as a collection of mostly grizzled, middle-aged men can be considered diverse.

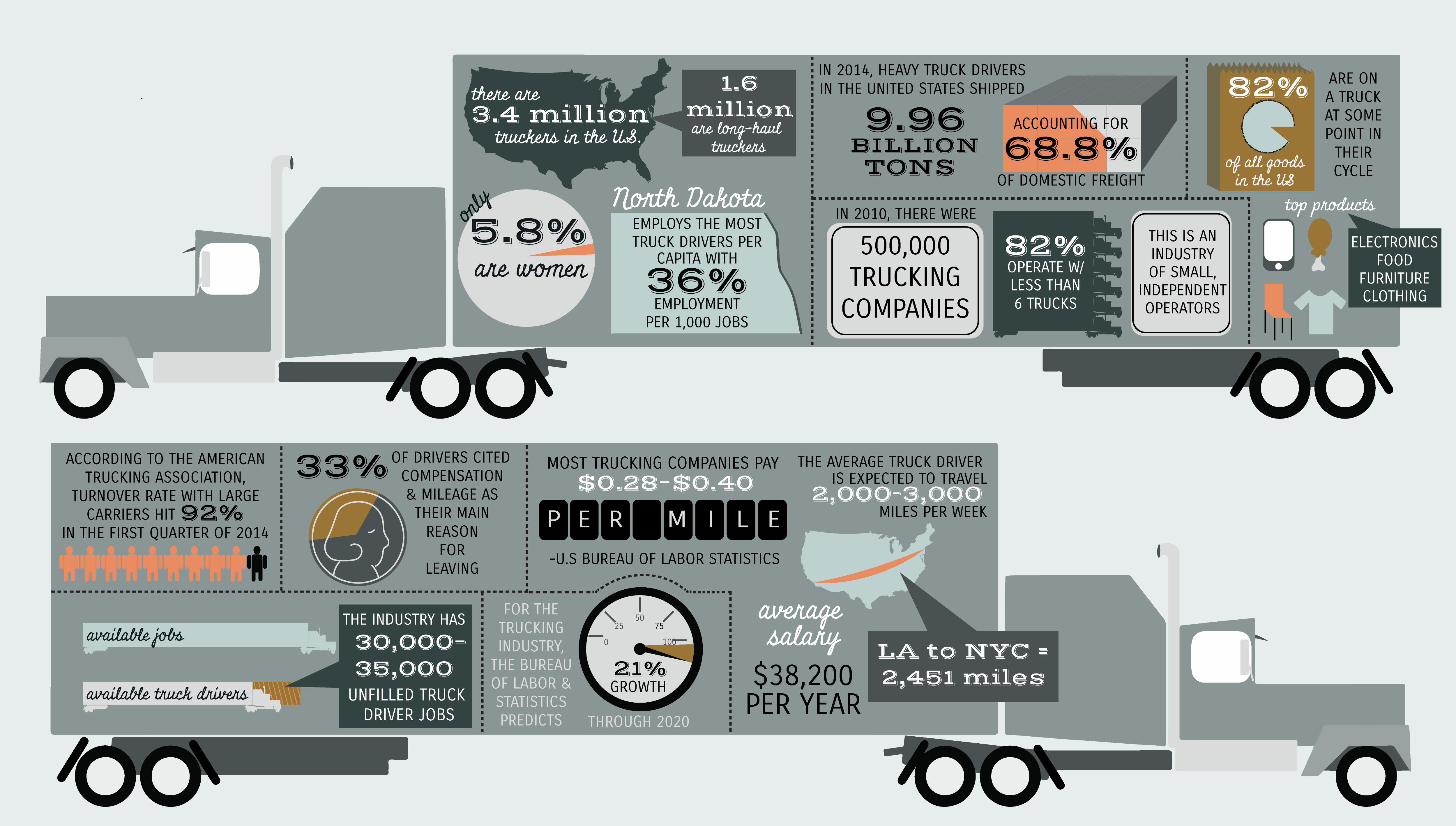

If they discuss their jobs at all, it’s to pool information about employers—which ones promise more than they can deliver, which ones maintain their vehicles properly, which ones take your phone calls. The job’s constant petty slights and grievances are hardly worth recounting at the end of the day. There is a sense, among long-distance drivers, of a universal lack of sympathy for the utterly essential service they provide. It’s an old-fashioned profession, but it remains more central to the fabric of our lives than many would suspect. These are the people who sleep in parking lots, shower in gas stations, and together sustain the entire American economy.

As new trucks pull up to Fuel Island hauling massive, unwieldy 50-foot long trailers, the drivers hop out and quickly wipe down their windshields with squeegees. Inside, they line up to purchase supplies for the next leg of their trips. You can find nearly anything you’d need here: oil stabilizer, upper cylinder lubricant, transmission sealer, hub oil. There are used DVDs, small coffee makers and rice cookers that run on generators, 18-packs of Busch for $12. There are racks of camouflage sweaters and thermal underwear, and all different types of suspicious-looking ephedrizine pills in vibrant colorful packages, with thrilling names like Swarm and Rhino Rush. You can send a fax here, or make copies, or watch the news.

One of the managers on duty, Diane, gets caught up watching a report on television about a mass shooting at a college. “It’s like I tell my kids,” she says to the room, “anytime you leave your house, you don’t know if you’re coming back. You might just as well never come back.” She looks to be in her 50s, and spends most of her eight-hour shift compulsively wiping down the coffee counter and scolding late co-workers. She is also a den mother for the drivers, who tease her while she works. One of them, a man with a reddish goatee, is wearing a denim jacket with the sleeves cut off at his shoulders; on the back is a heroic-looking semi-truck, an American flag, and the words “American Pride.” He hugs Diane before he leaves. “Buy me a new truck while I’m gone,” he says, “I’ll pick it up on my way back.”

12:00 P.M.

On the outside walls of the truck stop, large photographs give you glimpses of the food supposedly available: pepperoni pizza with steaming, just-melted cheese; tall sandwiches with elegantly folded slices of turkey and lettuce; pillowy biscuits with bacon and eggs, all captured in front of a pure white backdrop and the slogan, “Really fresh, right here.” What you find inside are the dark flip-sides of these pictures: lumps of chicken-fried steak, chili that looks like molten lava, corn dogs and taquitos left rotating on metal grates for hours at a time. For the health conscious, there are pre-packaged salads and plastic cylinders of hardboiled eggs and pale cantaloupe.

I eat a corn dog and watch a white flatbed truck drive up carrying three large and unidentifiably complex pieces of industrial machinery. Steve and his wife Inez topple out of the driver’s side door and leave their three chihuahuas in the cab while Inez smokes a cigarette and Steve runs to the restroom. The dogs line up in a row and stare out the window plaintively, their barking inaudible over the engine. Inez tells me they prefer to take their pets everywhere they go. “We like to keep them close,” she says. The corn dog is cold on the inside.

I watch a mother wait to meet up with her son, a long-haul trucker who arrives looking disheveled in a black T-shirt and jeans. The mother, who keeps her long gray hair tied back in a ponytail, nearly cries when she sees him, cupping her hands over her mouth. He buys a gallon of water and they hug and sit together beneath the TV, now on the Weather Channel, which is warning of severe flooding along the East Coast. She gets the meatloaf, he gets two slices of pizza, and they catch up. After a while, they stand and hug again, and then walk out to their respective parking lots and leave. I’m left with Tyrone, an Army vet with a rough, salt-and-pepper beard. He’s heading back to Dallas from Memphis with a load of fuel for a company called Celadon. “You know, it’s whatever,” he says, shrugging. A car alarm starts up from the front lot and bleats aggressively, apparently unnoticed by its owner. We ignore it, but I notice Tyrone’s right eye twitching in sync with each honk.

4:45 P.M.

Outside on the patio, Lynn, a cashier with steely blonde hair and a dark sunburn, takes a smoke break and sits watching the rigs cycle through the diesel lanes. She’s new to the job, she says. She spent 30 years living in Mount Vernon, Iowa, before moving back to nearby Arkadelphia to take care of her elderly parents. Her ex-husband was a trucker.

“He liked to always be making money,” she laughs. Lynn used to go on long runs with him, and when they had kids they would sometimes bring them along for the equivalent of a paid vacation. “That’s how we took our trip to Florida,” she says. Now her oldest son drives full-time, having just completed a six-week course for his commercial driver license. He lives in Iowa still, though she gets to see him on his occasional passes through the area. She mostly likes working at the Pilot. “It’s better than Walmart,” she says.

On TV the flood warnings have become dire. The meteorologist calls it a “one in a thousand year flood,” and describes a scenario in which “streets turn into lakes.” Over the loudspeaker, a programmed voice interjects every now and then to say things like: “Shower customer 61, your shower is ready. Please proceed to shower two.”

An older man in a denim jacket and blue jeans holds up the line at the counter, because he can’t seem to hear the cashier properly. “You’re gonna have to go slow,” he tells her. “I can’t hardly understand what you’re saying.” When he sits down, he tells me he’s from south central Missouri, drove a truck for 25 years before quitting for 12, and just started up again three weeks ago. He’s an independent operator, and proudly differentiates himself from “these company drivers,” with their Bluetooth headsets and elaborate corporate logos. After we talk a while, I tell him I’m writing a story about trucking, and he narrows his eyes. “I was born at night, but I wasn’t born last night,” he says. I must look puzzled, because he leans in closer and says, a little quieter this time, “What are you really doing here?”

8:30 P.M.

For dinner I take a closer look at the pizza, and decide to see what else is within walking distance. I walk down the street to The Mirage, a bar and grill with a group of pool tables and five TVs all playing the same football game. The crowd is a healthy mix of truckers, who sit quietly at the bar, and locals, who intermingle and occasionally shout furiously at a TV. “You had one job!” one of them says. I drink a Miller Lite under a poster of Eli Manning and order something called a quesadilla burger.

When I get back, I discover that the Pilot has unexpectedly transformed into a popular community dessert spot, and the soft-serve ice cream station is finally getting the attention it deserves. High schools kids and their well-dressed parents fill Styrofoam bowls of the stuff, covered in sprinkles and chocolate chips and caramel syrup. Their exuberance contrasts sharply with the zombie gaits of the truckers straggling in from the back lot, clearly unsettled by the make-up and blazers and general good cheer. They steal glances at the families while shuffling down the aisles grabbing gallons of water and chips and DVDs to watch while falling asleep. By this point in the night, thanks to my own lack of sleep, I’m on the drivers’ side of the population divide: wired, unshaven, paranoid. It’s either unseasonably cold or I’m losing my grip.

I decide to take a shower, and take my place in the queue. When my number is called, I walk down a back hallway and find a series of rooms accessible by keypad. I type in the four-digit pin on my receipt, and inside is a clean, gorgeously tiled bathroom worthy of an upscale hotel. Fresh towels and washcloths are stacked neatly by the sink, and there seems to be endless reserves of hot water. I get an immediate second wind, and feel briefly jealous of the truckers who get to use these showers all the time, before the absurdity of that feeling sinks in.

3:00 A.M.

After midnight the Pilot becomes both busier than ever and, somehow, more desolate. There is a sensation of being outside of time, a hallucinogenic feeling, as though the rest of the world is winding down while the routine here continues apace. Over by the TV, I meet a jumpy, talkative driver named Josh, who tells me that he lives in his truck. “I don’t have a home,” he says, before offering to give me a tour. As we walk out toward Fuel Island, he explains that he’s from North Carolina originally, from a whole family of truckers, though he’s been a driver himself for only two-and-a-half years. He wears a blue nylon windbreaker and has a long, patchy beard. His truck is bright orange, with the name “Schneider” painted on the side in black.

The interior of the cab is dark and spacious, a crowded cockpit with a dreamcatcher hung from the rearview, plus various other baubles and stickers ornamenting the area. Beside the steering wheel is a small digital display with a keyboard, a device called a Qualcomm, which trucking companies use to keep track of their drivers (and vice versa). In addition to your location, it monitors your driving status (on duty or off), your speed, and your idle time, and it offers a direct line to dispatch. The device reminds you where you’re going—and when it’s time to take a break.

Josh steps behind the front seat and gestures proudly toward the bunk beds, one of which can be folded up to create more space. Behind the passenger seat is a mini-fridge, on top of which is a small television. “Got my TV, my PlayStation,” he says. “I just set it up, play it ’til I fall asleep.” He says truck driving was easy enough to get started in, even without his family connections. “As long as you’ve got no felonies, you’re pretty much good to go.” Would he recommend it? “I’ll put it to you like this,” he says. “Most of my checks are anywhere from $600 to $800 a week. Hauling anything from tampons to fucking computers.”

I ask him if it’s true that he doesn’t have a home, and he shrugs. “I got a homestead,” he says, meaning his parents’ house. “I go chill there, but even then I sleep in my truck.” Josh never felt especially welcome in his hometown. He prefers his life to be in perpetual transit—he’s already driven all over the country several times in his brief career. “I just came from Laredo, Texas,” he says. “I’ll probably grab another load going up to Ohio tomorrow. I can be home every weekend with this company, but me personally, I don’t care to, man.” I ask him why, and he hesitates, then shrugs.

“There’s no sense in it.”

Lead Photo: A truck stop in Caddo Valley, Arkansas, in September 2015. (Photo: Will Stephenson)

The Keep on Truckin’ project is an effort to shine a light on the past, present, and future of the truck-driving industry in America, exploring all facets of our most pivotal, and overlooked, economic engine.