“The archaeologists of some future age will study [the freeway] … to understand who we were.”

—David Brodsly, L.A. Freeway: An Appreciative Essay

“Thanks to the Interstate Highway System, it is now possible to travel across the country from coast to coast without seeing anything.”

—Charles Kuralt, Charles Kuralt’s America

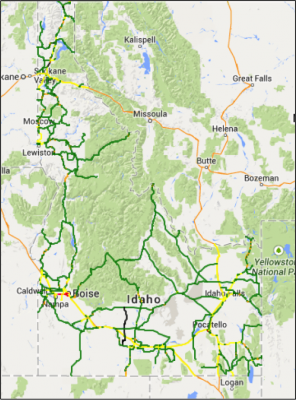

When I was growing up in rural Northern Idaho, my family did a lot of driving. Not in town—“rush hour” was when the mill changed shifts and you had to wait at a red light—but to everything else that wasn’t school or church or a drive-in movie theater. We drove to the reservoir to swim, we drove to go the Sawtooth foothills to go Morelling, we drove to the Sawtooths to ski. We drove two hours to get new school clothes at the closest legitimate mall, and we drove those same two hours to catch a plane that didn’t add an extra $200 to each ticket. We drove to summer camp in Northeast Washington (three hours) and family backpacking trips in Glacier Park (seven hours), to Huckleberry Heaven (two hours) and Lake Pend Oreille (five hours) and Lolo Hot Springs (3.5 hours).

And all of that driving was on two-lane highways. “Highway,” I’ve learned, is a highly contentious term; some even use the word to describe anything where your car gets to go over 55 miles per hour. But in the rural West, it’s the word we use for the roads we take to get out of town. Anything bigger—anything with two or more lanes on one side of the road for more than a few miles, anything with a dividing island, anything envisioned by Dwight D. Eisenhower—that’s a freeway.

I can’t remember being on a freeway until I was 11 years old, and even then, it was in Nebraska. I myself didn’t drive on one until I was 20. Freeways were for city people who spent their car-time idling next to others, peering into each other’s cars, honking horns, and doing things like waiting at stoplights.

Highways are for A.M. radio, sections so curvy there’s not a passing lane for miles, and gas stations that sell nightcrawlers and gizzards from the same ice chest. When you pass a semi on a highway, you feel awesome, in part because every time you do it you are willfully placing yourself in front of incoming traffic. And because highways go where freeways cannot, the land they cover is much more beautiful than the flat nothingness of the freeway corridors. Zombies drive on freeways; real men and women drive on two-lane highways.

I’m exaggerating, of course. But if we agree that driving has come to shape the quotidian rhythms of most Americans, then it’s crucial to think of how certain Americans—namely, the ones that live in the massive swaths of lands between interstates and urban centers—experience driving differently.

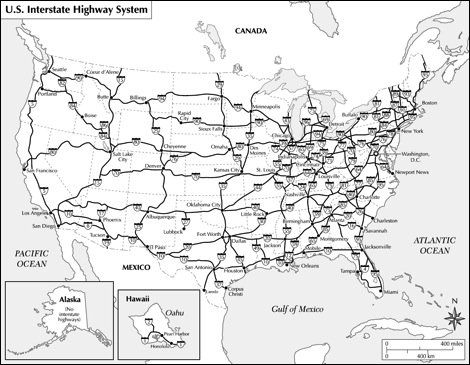

Take a look at the map of the U.S. Interstate System below, and it’s not that surprising:

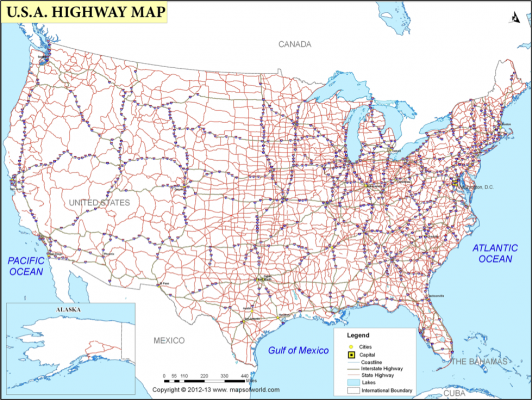

The interstates go where the people are, and the interstate density is a near-perfect reflection of population density. But it’s not as if the people whose lives don’t intersect these dark black lines don’t go anywhere—they just don’t (usually) take freeways. The map below gives you an idea:

Look at all those red lines! Those are the red lines of awesomeness, the red lines that I love. They’re the cross-hatching that fills in the vast “emptiness” between major metropolitan areas. But if you grew up where I did, where I live now, or in any of those substantial white areas, those red lines meant something familiar and, usually, beautiful. They cut through mountain passes, they wrap around bodies of water; there are places where the forest still threatens to take the whole enterprise under. They’re often isolated, usually dangerous, and absolutely my favorite way to travel.

Rural highways are the closest we come to the ways that people a century before us traversed and appreciated the land. The decrease in speed, either in accordance with posted speed limit or because of the truck hauling a horse trailer in front of you, forces you not only to consider the wildflowers of the field, but the towns you pass through on the way to your destination.

Between Walla Walla (my current town) and Lewiston (my former town), you pass through the bottom of the Palouse, with miles of undulating wheatfields that gradually turn from vivid green to gold, move into the foothills of the Blue Mountains, and climb to the top of Alpowa Pass, where, in summertime, the spiraled hay stacks spread out for miles. It’s not a scenic byway, and no traveling retirees divert to Highway 12 on their North American trek, but it’s the most exquisite landscape I know—in no small part because I’ve driven it more than 300 times. Like so many of the old highways, it was originally a wagon route, and there’s a town (or, more precisely, a settlement) every 10-12 miles, corresponding with the distance a wagon could travel in a day.

Dixie, Waitsburg, Dayton, Pomeroy, Pataha—plus a handful of clusters, usually nested in a bend in the road, where two or three massive old farm homes and the broken carcass of a diner or gas station busy themselves with finally falling down. In the middle of a field, a whitewashed old schoolhouse loses a window every year; a bleached out barn that collapsed upon a winter’s worth of hay just sits and stays. Outside Waitsburg, a man who didn’t want to cede to the county’s districting demands simply started depositing old trucks, tires, and machinery in a long line that now stretches three miles from his home.

Garfield County Courthouse in Pomeroy, Washington. (Photo: jimmywayne/Flickr)

But it’s not all readily fetishized desolation. Two of the towns have majestic county courthouses that look like something the girls of Little House of the Prairie would’ve marveled at when they came to town. It’s not the grandeur I associate with the construction of New England, but the humble downtowns do something purposeful: The tiny theater in Dayton still plays second-run movies, and at least two diners in Pomeroy, population 1,425, are always nearly full. I’ve never spent the night in any of these towns, but I know all about them because I’ve driven them so often, slowed down to 20 miles an hour, stopping for their pedestrians and buying gum in their gas stations.

I know these towns, and I know the land that brought people to them. They feel as essential to my understanding of home and place as the streets of my neighborhood or the route I drove to school. Some people drive those roads everyday to work in the “big city” of Lewiston or Walla Walla, but if a city commute is dictated by presence—the car in front of you, the one merging into you—these commutes are all about absence: how many songs until the next town; how many minutes until cell reception; how many miles until you see the next car.

But even people who don’t commute, they take these roads on some sort of regular. Nearly everyone I grew up with had family in the next town or the fourth town after that, and all the schools in our sports leagues were anywhere from 30 minutes to four hours away. Most weeks in high school, I spent my afternoon traveling on one of those highways, my face smushed against the bus window, looking out at nothing and everything, a Discman with Tim McGraw in my ears.

This all might seem very specific to my own experience, but look at the map above and understand it was not. Even if we, as a nation, have passed “peak car,” the dynamics that precipitate that trend don’t, as a whole, affect people who grew up where I did. When there’s no public transportation, and your parents do shift work, and you live five to 25 miles away from school, someone’s still gotta take you home from practice, and usually that person is you, in the F-150 that’s been in your family for decades. Today, I live minutes from where I work and shop, and drive my car five miles a month—save, of course, when I go on the highway to go where the trains, buses, and planes can’t take me.

Look back at all the white spaces on the map at the top, and imagine thousands of kids, staring out from the backseat, asking questions about the world they see. We’re everywhere: We’re the ones who tried to find the actual middle of nowhere—the place where you couldn’t see a sign of civilization, save the road itself. We feel lulled to sleep by the freeway and unsettled with the anonymity of the rest stop. We hate cruise control; we’ve mastered the two-fingered steering wheel wave. We love to drive, but only in the specific way of our youth, the way we watched our parents drive—the way we imagined moving across the land would always be. Next time, take the two-lane highway: See the world as we know it.