Americans have a spotty understanding of the risks of Tylenol, a nationwide poll conducted earlier this year shows.

About half said they are not aware of any safety warnings involving the drug. But 80 percent said that overdosing on the medicine could result in serious side effects.

Thirty-five percent of those surveyed said it was safe to mix Tylenol with another medicine that contains acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol. This practice is known as “double dipping” and can lead to accidental overdoses.

Taken together, the results suggest a mixed record of success for the labels on Tylenol packages intended to warn consumers about the dangers of the drug. It also suggests that the acetaminophen public awareness campaigns sponsored over the past several years by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the drug industry and McNeil Consumer Healthcare Products, the Johnson & Johnson unit that makes Tylenol, have yet to be fully effective.

When taken as recommended, acetaminophen—known in many countries as paracetamol—is generally safe, with few side effects. But at higher amounts, it can damage the liver, sometimes with lethal consequences.

As an investigation by ProPublica reported last week, about 150 people die each year after accidentally ingesting too much acetaminophen, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tens of thousands more are sent to hospitals and emergency rooms for treatment from acetaminophen poisoning, studies show. The FDA now calls acetaminophen toxicity a “persistent, important public health problem.”

The telephone poll of 1,003 adults was conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International in February and March, and it has a margin of error of 3.5 percentage points. It was commissioned by ProPublica and “This American Life,” which produced a radio story on the risks of acetaminophen. Full results from the survey are here.

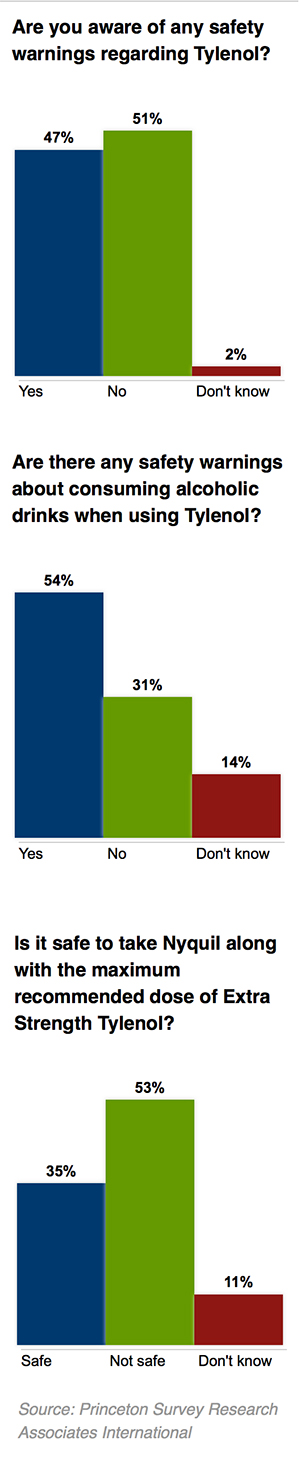

Fifty-one percent of poll respondents were unaware of any safety warnings associated with Tylenol. However, 68 percent correctly said that liver damage could result from taking too much of the drug, while 55 percent said that an overdose could lead to death.

To gauge whether these responses reflected a real knowledge of the dangers of overdosing, the poll also asked about problems that are not caused by excessive consumption, including heart palpitations, tingling in the fingers, and severe brain damage. But large numbers gave the wrong answer. For example, almost half of those surveyed (49 percent) said incorrectly that overdosing could cause heart palpitations, calling into question how much Americans truly understand about the risks of overdosing on acetaminophen.

A little more than half of those surveyed—54 percent—said they had heard of warnings about mixing Tylenol and alcohol. Studies have shown that alcohol can make the liver more susceptible to damage from the drug. The FDA warns consumers on product labels against taking acetaminophen after three drinks.

Sizable numbers of Americans also said they believed it was safe to take several different medications containing acetaminophen at once, the poll found.

For instance, 35 percent of respondents said it was safe to combine the maximum recommended dose of Extra Strength Tylenol with NyQuil, a cold remedy that also contains acetaminophen. It is not, according to the FDA.

People who take multiple acetaminophen products may inadvertently exceed the FDA’s maximum recommended daily dose of 4 grams, or eight extra strength acetaminophen pills. The FDA has cited reports of people suffering liver injury after taking between 5 and 7.5 grams per day over several days. ProPublica has created a simple app that allows people to look up how much acetaminophen is in many common drugs.

Regulators worry that people don’t understand that many medicines contain acetaminophen—more than 600 in all, including commonly used prescription drugs such as Vicodin and Percocet.

Michael S. Wolf, a professor at Northwestern University’s medical school, has studied double dipping and says the practice is “a reflection of how horrible our health system is at communicating the active ingredients” in medications.

The FDA has required over-the-counter acetaminophen to carry a warning that the drug can cause “severe liver damage” since 2009. While it mandates that prescription medications containing acetaminophen warn that overdosing can lead to “death,” no such warning is required for over-the-counter acetaminophen. About 60 percent of the drug is sold without a prescription.

The FDA’s Safe Use Initiative provides advice on how to correctly use acetaminophen through pamphlets, a webpage, and YouTube videos, the most popular of which has been seen some 19,000 times since it debuted in January 2011.

“Public education and public campaigns are not something that the FDA is well resourced for,” said Dr. Sandra Kweder, an FDA official who helps regulate the drug and appears in the video.

The maker of Tylenol—McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a division of Johnson & Johnson—sponsors its own informational website, Get Relief Responsibly. The company also has created television advertisements, posters for doctors’ offices, and a YouTube channel to educate consumers.

“McNeil has been a leader in educating doctors and providing materials about overdose and misuse of medicines containing acetaminophen,” the company said in a statement. It said its “acetaminophen awareness messages have been seen over one billion times.”

The Consumer Healthcare Products Association, an industry group representing McNeil and other acetaminophen makers, has worked in consultation with the government to create the Know Your Dose education campaign.

“We want to be as constructive and helpful as we can, to say, ‘Read and follow the label, taking too much can lead to liver damage, and don’t take two products at the same time,'” said Emily Skor, vice president of communications for the organization.

This post originally appeared onProPublica, a Pacific Standard partner site.