In June of 1998, the U.S. Congress, with bipartisan support, committed itself to double the National Institutes of Health (NIH) budget over the next five years, arguing that “biomedical research has been shown to be effective in saving lives and reducing health care expenditures.” Shortly thereafter, a trio of scientists representing the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology laid out a vision of what increased funding could achieve: it would help the biomedical research community take advantage of an “untapped reservoir of talent and an underutilization of valuable human resources” by encouraging more innovative project proposals, and by helping more young scientists start their own labs, leading to a more productive scientific enterprise.

Congress finished doubling the NIH budget in 2003. Now, 10 years later, success rates for grant proposals have plummeted to historic lows, and the proportion of labs headed by young scientists has declined to nearly half of what it was in 1998. What happened?

The failure to sustain the NIH budget after it doubled is wreaking havoc in the biomedical research community.

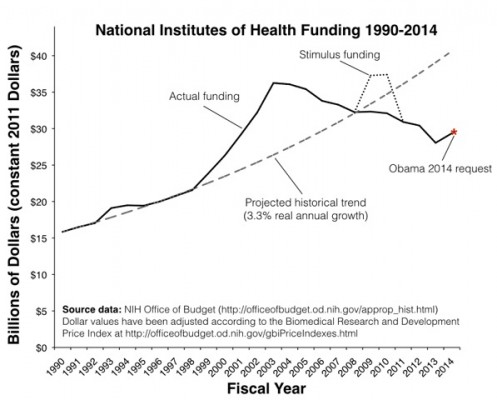

A big part of the answer is that the U.S. government is letting the nation’s biomedical research infrastructure go to seed. Like my former landlord who paid for a major remodel of his property, and then let his investment decay out of utter neglect, the U.S. government built up our nation’s biomedical research capacity, and then let the NIH’s purchasing power steadily erode for a decade. In 2007, an analysis published in The New England Journal of Medicine showed that decline of the NIH budget since 2003 would soon bring it to what it would have reached anyway if had Congress simply stuck with its pre-1998 historical trend of modest annual increases.

And that was before the economic crisis struck. The NIH received a sizable boost in 2009 as part of the financial stimulus legislation, but that was gone after two years. The worst hit came earlier this year, when the NIH had to trim five percent from its annual budget, six months into the fiscal year, in response to Congress’ sequester legislation. The Obama administration’s budget request for the 2014 fiscal year is $31.3 billion, more than 23 percent lower than the 2003 funding level in purchasing power, and almost 40 percent less than where a projection of the historical trend would put it (see the figure below). All trace of the doubled NIH budget has vanished, along with similar efforts to double the budgets of other science agencies (PDF).

Predictably, the failure to sustain the NIH budget after it doubled is wreaking havoc in the biomedical research community. It has changed how scientists spend their time and even the very makeup of the biomedical community. Because funds are scarce, scientists are spending more of their time writing and re-writing more grant proposals, each of which has an increasingly smaller chance of getting funded. The tighter competition for funding has put the squeeze on younger scientists with fledgling labs; the proportion of young scientists with NIH grants is half of what was in 1998, while the proportion of funded scientists over 65 has doubled. Because scientific training typically takes over 10 years, students who decided to enter graduate school in the boom days of the mid-Aughts are now entering a job market that looks nothing like what they expected.

The budget crunch has been bad, but there is a strong case that the biomedical research community’s problems stem from more than a simple lack of money. A major effect of federal R&D funding policy over the last decade has been to exacerbate trends and structural problems that were evident well before Congress committed to double the NIH budget.

Paula Stephan, an economist at Georgia State University, argues that many of the research community’s problems flow from two big features of how we do research. First, we staff our labs with low-wage, temporary workers—graduate students and postdoctoral fellows who move on after a few years. This means that universities have an incentive to recruit and train more students and postdocs, regardless of their eventual job prospects. The result is unsustainable. As Stephan writes, “the research enterprise itself resembles a pyramid scheme.”

The second structural problem is that career rewards in science are doled out according to a “tournament model,” a situation in which small advantages—in productivity, skill, or network connections—translate into large differences in rewards like faculty jobs, grant funding, and tenure. Tournament models foster intense competition, but they can be incredibly wasteful: the differences between a proposal that is funded and one that is not can be small and arbitrary. These small and arbitrary differences are making and breaking scientific careers in which taxpayers have invested substantial resources. As Stephan writes in her book How Economics Shapes Science:

The public has invested resources in tuition and stipends. If these ‘investments’ are then forced to enter careers that require less training, resources have not been efficiently deployed. Surely there are less expensive ways to train high school science teachers than to turn PhDs who cannot find a research position into teachers…. The current system may be “incredibly successful” from the perspective of faculty, as a recent report described it, but at whose cost?

These structural problems are deeply ingrained in our current research institutions, and solving them will require difficult decisions regarding how to fund scientific training, and whether to stop staffing labs primarily with temporary workers. More money by itself certainly won’t solve the structural problems of the biomedical research community.

But we’re not solving any problems by letting our substantial investment in training and research infrastructure erode away. Not only will we get less overall R&D, we’ll get a system that is too risk-averse, one that fails to nurture the next generation of scientists, and one that promotes those who can work well in the hyper-competitive environment, while discouraging others who’re looking for a better work-life balance, or whose scientific instincts lead them off the well-trod path, into potentially revolutionary, but less immediately publishable territory.