This post was produced in partnership with Beacon Reader as part of a crowd-funded reporting project, “After Ebola Comes Hunger.” Read more about our support for this project, and pledge your support here.

“It really doesn’t matter if you don’t like this song … what you have to do is buy this thing,” Bob Geldof said at a press conference for the re-release of Band Aid and its Ebola-themed single, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?,” last month.

While the new single broke United Kingdom sales records for 2014 within days, many people criticized its representation of Africa (“a place of dread and fear”) as counterproductive. Referring to songs by Africans that have the same pro-social goals, Liberian researcher Robtel Neajai Pailey told Al Jazeera, “We got this, Geldof, so back off.”

Paul Farmer has said that aid workers’ intentions are derailed by their failure to do “scut work,” or menial tasks. In Ghana, locals assumed I was pampered, unproductive.

Rejecting Band Aid is the peak of a Kilimanjaro of discontent. In another essay, Pailey criticized international efforts against Ebola as a “white savior complex,” “a pathology of white privilege” based on the ill-conceived concept that Africans can’t survive without Western interventions. Nigeria’s defeat of Ebola has been ignored because it doesn’t fit the white savior pattern, she wrote. Similar articles suggest foreign-backed Ebola care is akin to “voluntourists” at fake orphanages.

A friend sent me Pailey’s essay when I began organizing a trip to West Africa. Her critique, it seemed, was that I was a self-indulgent racist for even considering going.

I’m going back, actually. I lived in Ghana in 2010 while working with a non-profit school located a long day’s drive from Pailey’s country, Liberia. While Ghana is relatively politically stable and prosperous, the complaints against foreign intervention ring true there, too. My time there showed me that meaningful collaborations are often constrained due to long-standing inequality—but they are possible.

It’s easy to mock foreign involvement in sub-Saharan Africa as self-aggrandizing nonsense. Africans do this with fake charity songs. Americans add sarcasticjabs. Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina satirized lazy clichés in a Granta magazine essay, “How to Write About Africa.” (“An AK-47, prominent ribs, naked breasts: use these.”) It’s the most-forwarded article in Granta’s history.

There are broad identity issues that underlie difficult interactions between locals and foreigners. When it comes to puncturing the clichés, though, I think of a specific human being: Samuel Amponsah.

AMPONSAH WAS A TEACHER at the school where I worked. He single-handedly taught 50 kids younger than five years old. He was well qualified: raised in the village, he’d earned a teaching certification in a larger town nearby. His life hadn’t been easy. In the 1990s, he’d been the pastor of an urban church. “But unfortunately,” he told me in 2010, “I had an accident.” In 1997, he was in a motor vehicle collision that injured his left shoulder and both legs. Lasting disability pushed him into unemployment until the school hired him in 2001.

The non-profit could not pay what he was worth. As a single father, he found it difficult to pay for education for his own five kids. Nonetheless, he stayed at the school. “It’s because I have patience and love for the children,” he said.

In short, Amponsah did a bunch of things “How to Write About Africa” says Africans are never depicted to do: “laugh, or struggle to educate their kids, or just make do in mundane circumstances.” He evoked—and yet partially belied—an archetype in the article: “The Loyal Servant … is good with children, and always involving you in his complex domestic dramas.”

Loyal and good with children, yes. But on personal problems, Amponsah was reticent. Although he acknowledged his pressing need for a raise, he insisted, “The only thing I would say is that I love the school. I love the school. And so, we need help so that the school may grow. That’s the only thing I want.”

MY GUIDEBOOK SAID LOCALS tended to regard foreigners as “a walking ATM.” One acquaintance told me outright that he believed “all obronis [white foreigners] are given a big pile of money when they are born.” The myth meant many people tried to score gifts through awkward favors: bending to wipe imaginary dirt off my shoes, for instance. Others attempted guilt-trip sales pitches like Geldof’s (“It really doesn’t matter if you don’t like this”). Relations between Africans and foreigners felt hamstrung by clichés, despite everyone understanding how obnoxious the stereotypes were.

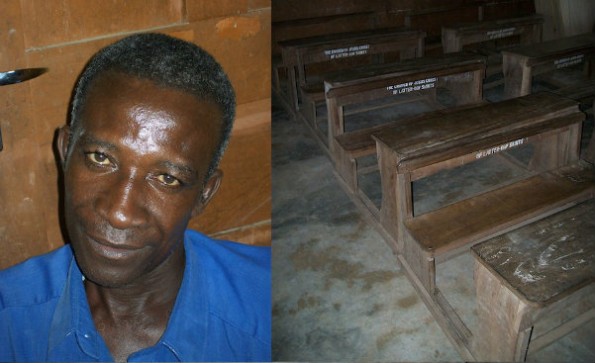

Samuel Amponsah and his classroom. (Photo: M. Sophia Newman)

While we, as foreigners, have spent time dissecting where our own prejudices come from, it’s just as informative to consider how we come off to those we attempt to aid. Perhaps the stereotypes reflect the economic pressures in Ghanaians’ lives, or the internalized aftereffects of colonialism. Perhaps they are an accurate reading of foreigners’ behavior. Humanitarian doctor Paul Farmer has said that aid workers’ intentions are derailed by their failure to do “scut work,” or menial tasks. In Ghana, locals assumed I was pampered, unproductive—as useless as a Kardashian.

The way Amponsah defied archetypes gave me an opening to cease playing my own tiresome role. I knew he was overwhelmed with work, and there was no one to clean his classroom. So I made a plan. One day, after I finished administrative work at the school, I pocketed his keys. At midnight I returned. By flashlight, I stacked desks and benches to one side, swept and swept again. I churned up red dirt from the concrete, washing it away with buckets of water. I scrubbed tiny hand-prints off of walls.

I hoped the help would augment the well-being of students and teacher alike. I also wanted to repay his open-hearted hard work with practical support.

At seven, Amponsah arrived. I was sweeping the porch. “You did a nice job,” he told me. Silently, he helped with the last of the cleaning. Then he paused. “You did very good work,” he said again.

The only portable solution is to understand that each place has its own answers to complex problems; international help is always limited.

I was too fatigued to say much. But my thoughts were reminiscent of Pailey’s critiques. About Africans, she wrote, “While we welcome genuine collaboration, we remain our own heroes and heroines.” Discourses around Africa too often cast Africans as bit players in some foreigner’s exotic adventure. Here, Amponsah was the protagonist. It was his school; I was a footnote in his story.

BAND AID IS A mere footnote, too. The song funnels Western cash to fight Ebola, addressing the profound inequality that hinders Africans’ own efforts against the disease. But few West Africans are actually listening to Geldof’s sappy choir. To them, the song is hardly worth noting. On the other hand, the song Pailey name-checked, “Africa Stop Ebola,” has been widely played in West Africa. Its lyrics present health messages to people at risk—an entirely different goal than Band Aid. Its importance is in public health, not fundraising.

There is no one solution that makes sense. Attempts to roll out developments worldwide are often wasteful. The only portable solution is to understand that each place has its own answers to complex problems; international help is always limited.

The role a person can play is similarly constrained. In Ghana, I often had little choice but to accept how most people saw me—not as a genuine collaborator, but rather as a semi-useless money tree. Although Samuel Amponsah gave me hope that genuine exchanges were possible, it was clear that mere awareness is not enough to stop widespread misunderstanding. To alter our relationships also requires ameliorating global economic inequality. The same shift is necessary to address Ebola and its aftermath.

Change may be slow in coming. When I finished cleaning Amponsah’s classroom, I departed to meetings about fundraising. My African co-workers suggested the best solution was foreigners who would pay to simply be present. To fund Amponsah’s wages, they argued, we needed voluntourists.