Taylor Swift’s “Wildest Dreams” video is, as they say, problematic.

The problem is not that Taylor Swift’s video uses stereotypical images of Africa, though it certainly does tick off quite a few of Binyavanga Wainaina’s boxes. But if it were just that, it would be pretty unremarkable; stereotypes are, by definition, normal. Nor is the problem that the video uses the bodies of black people as props (as her video “Shake It Off” notoriously did). “Wildest Dreams” mostly doesn’t have any black people in it at all. There are a handful, but they aren’t even prominent enough to be objectified; if you blink, you’ll miss them:

That’s sort of the point: There are black people in this image of Africa, but they are in the background, serving. Otherwise, they are absent. This is Africa as a backdrop for white people taking selfies. This is Africa as white-supremacist fantasy, Africa as a romantic prop. After all, the video doesn’t show us “Africa” in any particular sense. It’s not set in Out of Africa’s Kenya, for example, or Botswana or Zimbabwe, or any other particular place; it’s set in “Africa,” timeless and placeless, an Africa that resembles the world of the Lion King more than anywhere real.

The white fantasy that Swift is selling is the idea that you can play around with racism but not get your hands dirtied by it. You can have your racist cake and eat it too.

And this is where the video’s cynicism is truly breathtaking: It doesn’t want the real thing; it wants the fantasy. “Wildest Dreams” (2015) is not set in Africa, but rather on the movie set of an imagined 1950 Hollywood film, Wildest Dreams.

This is why the video carefully shows the construction of a stereotypical image of Africa. We see the blazing African sun … and then we see the movie lighting that is used to create the effect.

We see Swift posing next to a wild animal—CGI, of course—but her dress is not being blown back by the real African wind; it’s being held aloft by movie magic.

We see make-up being applied, as she sings the words “red lips and rosy cheeks,” and we see the fantasy break down, as the camera pulls back from this shot.

And reveals that we aren’t even in Africa at all; we’re on a Hollywood sound-stage.

The fantasy on offer in this video, in other words, is not to actually be Karen Blixen, not to be the actual person who actually “had a farm in Africa” on whom Sydney Pollack’s Out of Africa was based. Swift’s video is a fantasy about being an actress, Meryl Streep, as she pretends to be Karen Blixen in Out of Africa (or Katherine Hepburn, or some other glamorous actress pretending to be in Africa). Swift doesn’t want to be in Africa in 1950 in other words; she wants to be an actress making a movie about being in Africa in 1950.

This may seem like a defense of the video. It isn’t, but I am saying something very similar to what the director of the video, Joseph Kahn, said in his defense of the video:

This is not a video about colonialism but a love story on the set of a period film crew in Africa, 1950. The video is based on classic Hollywood romances like Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, as well as classic movies like the African Queen, Out of Africa, and the English Patient, to name a few…. There is no political agenda in the video. Our only goal was to tell a tragic love story in classic Hollywood iconography.

The things he says are completely true: The video is not “about” colonialism (or about Africa); it’s about the desire for “classic Hollywood iconography,” for the glamour of that period. Kahn uses the word “classic” three times. Because Swift’s video is “based on classic Hollywood romances,” he insists, it cannot be about colonialism. Because it uses “classic Hollywood iconography,” there can be “no political agenda in the video.” Because it’s a tragic love story, it is absolved of nostalgia for white supremacy.

Hollywood sold white supremacy by foregrounding white romance. Gone With the Wind is not about slavery, ostensibly; it’s about white people in love who just happen to own slaves.

But if the word “classic” is a load-bearing piece of rhetoric, the argument here is a load of crap. Another “classic” Hollywood film is 1915’s Birth of a Nation—an adaptation of Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan—and the film’s success played a direct and decisive role in reviving the Ku Klux Klan, an organization that occasionally dabbled in politics. For decades, as black people struggled against Jim Crow repression and law-by-lynching, Hollywood films like Gone With the Wind (1939) produced very effective and powerful propaganda for a white supremacist vision of American society; Hollywood in the 1930s was, in everything but name, a public relations office for Jim Crow. But, and here is the point, Hollywood sold white supremacy by foregrounding white romance. Gone With the Wind is not about slavery, ostensibly; it’s about white people in love who just happen to own slaves. And it’s no coincidence that Birth of the Nation literally ends with voter suppression and white people getting married. The romance—the marriage between North and South—is there to make white supremacy look good, to make you forget little things like the fact that Black Lives Matter.

Like Gone With the Wind, Taylor Swift’s “Wildest Dreams” is not explicitly nostalgic for white supremacy. But it’s nostalgic for a time when you could be nostalgic for white supremacy, when having a wedding at a former slave plantation raised no eyebrows. As in “Shake It Off,” Swift’s previous flirtation with white supremacy, the white fantasy that Swift is selling is the idea that you can play around with racism but not get your hands dirtied by it. You can have your racist cake and eat it too: you can smirk at a line of twerking black bodies, but if anyone criticizes you, you can just shake it off.

This is precisely why the Black Lives Matter movement exists: because most white people would prefer not to take black lives seriously.

This is why Swift’s video seems primarily nostalgic not for white supremacy, per se, but for a time and a place when you could be nostalgic for white supremacy: classic Hollywood. And, to be blunt, “classic” Hollywood was racist; it was, to paraphrase Taylor Swift, really bad (though it did it so well). The bigotry of early Hollywood found vocal critics at the time, of course; the NAACP mounted a public campaign against Birth of a Nation, and however mainstream the minstrelsy of movies like Gone With the Wind were (both literal and figurative blackface were mainstream, for a very long time), it was always political, always protested, always called out. And the classic defense was always precisely what Kahn says above—i.e., to maintain that Gone With the Wind is not a movie about slavery or white supremacy: no, it’s just a love story that happens to be set against the backdrop of the civil war.

One difference was that, in 1939, a film about the Old South could be openly and nakedly nostalgic for slavery days, as the movie’s opening card makes explicit:

There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South…. Here in this pretty world Gallantry took its last bow…. Here was the last ever to be seen of Knights and their Ladies Fair, of Master and of Slave…. Look for it only in books, for it is no more than a dream remembered. A Civilization gone with the wind….

In 2015, it’s a little harder to be so openly and nakedly nostalgic for white supremacy, even if that’s how you feel in your heart. It isn’t quite so sexy to be overt about it. Even 30 years ago, Out of Africa’s white-washed and romanticized vision of Kenyan colonialism struck more than a few people the wrong way; after all, while Kenya’s white-settler state collapsed 25 years before Sydney Pollack made his movie, in 1985, the apartheid state in South Africa had not yet been consigned to the dustbin of history.

Nelson Mandela was still in prison when a film romanticizing white settlers won seven Academy awards.

Even in 1985, not everyone was oblivious to that irony. But, even today, Hollywood—and mainstream white entertainers like Swift—work hard to remain oblivious, to insist on the right to make iconography without being tarred with politics. For example, there was nothing surprising about MTV’s Video Music Awards featuring jokes about police violence, however shocking it may have been to see and hear. This is precisely why the Black Lives Matter movement exists: because most white people would prefer not to take black lives seriously. But you don’t make jokes about police violence at an awards show—as Rebel Wilson did—because you’re unaware of police violence against black people, or of the growing movement to top it. You make Black Lives Matter into a joke about “stripper police” because the reality makes you uncomfortable, and because you resent having to feel uncomfortable. You don’t want to listen to the haters; you don’t want to feel bad about white privilege. And so, as Taylor Swift taught us last year, you shake it off.

In Africa, you can turn back the clock. You can cast a few black people as porters, and leave them out of the shot. In Africa, you can make the collapse of colonial rule the backdrop for the collapse of a love affair.

At a certain point in the 1950s, it become a bit more impolitic to make movies about how great and gallant slavery days had been. This is not to say that Hollywood suddenly began embracing progressive politics, but it was harder to enjoy the nostalgic glow of Dixie’s moonlight and magnolias at a time when redneck sheriffs were setting dogs on black children. This was the 1950s; today, people might prefer to remember the 1960s as the moment when America got hip, but Brown v. Board of Education was decided in 1954, followed by the Montgomery Bus Boycott the following year (though if these landmarks in Civil Rights History are usually regarded as the beginning of the movement, it was on April 23, 1951, that 16-year-old Barbara Johns led a student strike for equal education at Moton High School in Prince Edward County, Virginia).

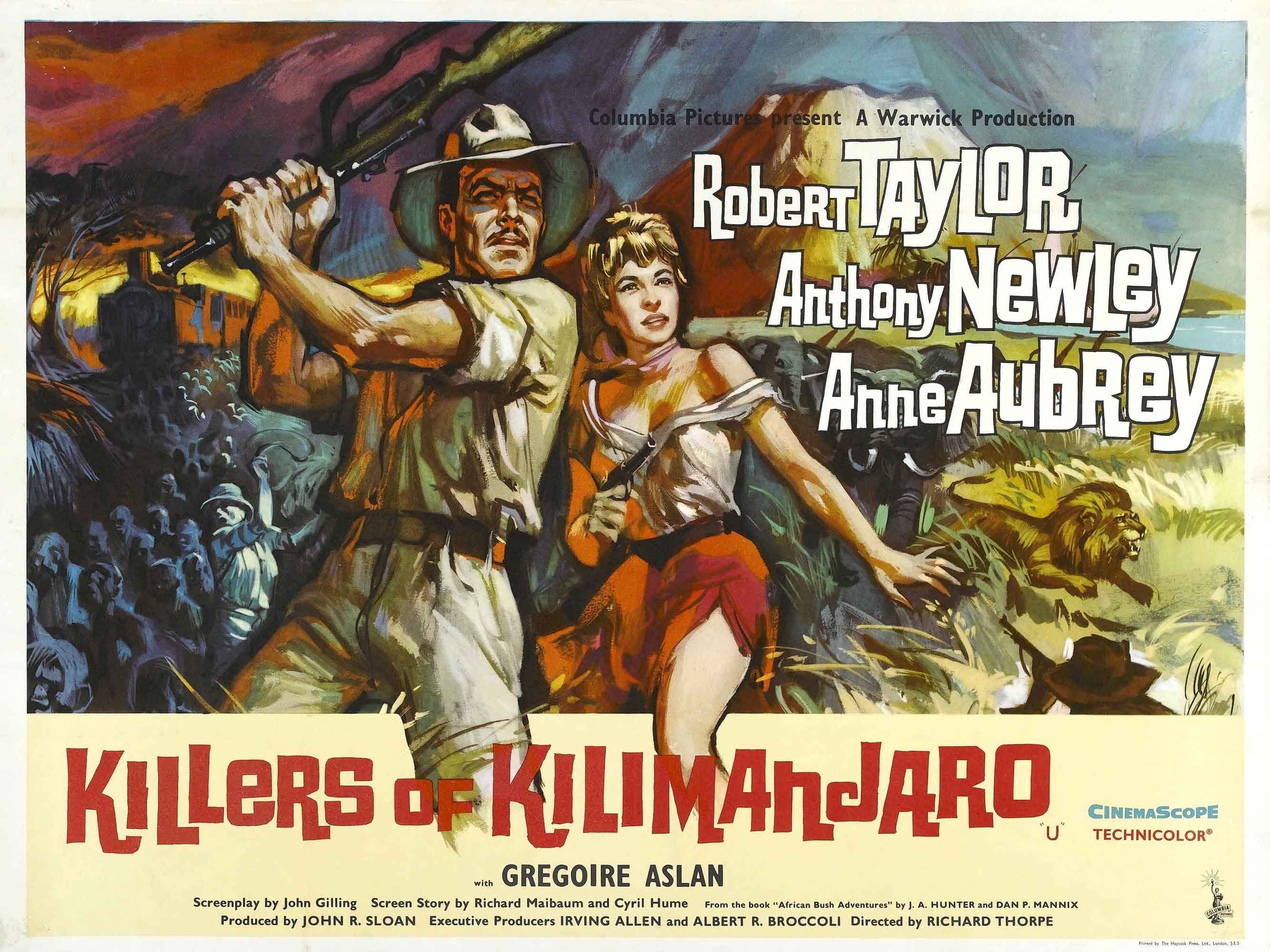

The 1950s, in short, was when American white supremacy got a little less sexy. And so, after the Civil Rights Movement had made it harder for white people to openly long for the bygone days, Hollywood stopped making movies about how glamorous it was to be white in a white supremacist America—instead, they made movies about how sexy it was to be white in a white supremacist colonial state in Africa. The 1950s was a golden era for safari movies set in Africa, and the convergence between white romance and black bodies is both disturbing and predictable. Here, for example, are some films from the 1950s about white people being sexy together in Africa.

These films were made—always about Kenya—at a time when Great Britain was fighting a long and ultimately Pyrric counter-insurgency campaign to put down what they called the “Mau Mau” uprising; the British liked this name because it fit the savage uprising they believed they were fighting (the “Mau Maus” themselves tended to use names like Kenya Land and Freedom Army). Britain would win the battle but lose the war; in 1963, Jomo Kenyatta would become the first president of independent Kenya, a black president who had, a few years earlier, been widely demonized as a Mau Mau general (he wasn’t, but that’s another story). This is why, for contemporary white supremacists, calling our black president a “Kenyan” is not just a way of marking him as foreign. It’s a way of marking him as a militant black power nationalist. In part, this is because black power movements in the 1960s and ’70s looked to a (romanticized) vision of Mau Mau as a model. As Gerald Horne observes in Mau Mau in Harlem?:

“Mau Mau” quickly became a metaphor for fierce resistance and was adopted as such by African Americans, before spreading as a verb to the population at large. In the heart of darkness that was Jim Crow Mississippi, Charles Evers—brother of the slain civil rights martyr, Medgar Evers—contemplated early on, “Why not create a Mau Mau in Mississippi?” That is, “each time whites killed a Negro, why not drive to another town, find a bad sheriff or cop, and kill him in a secret hit-and-run raid.” So, they “bought bullets and made some idle Mau Mau plans” before—presumably—dropping the idea.

American films about Africa were always also about America, which is why Hollywood collaborated in creating a romantic image of Mau Mau. The Mau Mau seen in films like Something of Value is a savage, atavistic cult, more indebted to decades of Tarzan movies (and contemporary British propaganda) than to anything in reality, but this is what it means to call Barack Obama a “Kenyan,” or to assert, hilariously, as this recent meme did, that “Denali is the Kenyan word for ‘Black Power.’”

Among Americans of a certain age, you could almost say that “Kenyan” is a word for black power.

Of course, Taylor Swift was born in 1989, which means that for her entire adult life, a black man has been president of the United States. For an American of her age, “Barack Obama” is the American term for post-racialism—the conceit that bad things once happened and that we’re over it now.

But of course we aren’t. And after Swift was widely criticized for using a line of black women’s bodies as a prop in her video even she must have become aware that she couldn’t just shake it off and keep moving. And that’s why this video doesn’t look forward, why it wants to look back, to 1950, back to a time when the Civil Rights Movement hadn’t yet made white supremacy un-sexy. (As clever observers have noted, the two actors in the video are actually named for Swift’s grandparents; if she was born in 1989, she wants to track her biography back to 1950. But if her grandparents had gone on a romantic safari in 1950—as more than a few upper-class Americans did at the time—and Swift comes from a long line of bank presidents, hilariously—then Swift’s grandparents’ romance would have occurred against the backdrop of the innocent white supremacist playground which Kenya had been for its white tourists.)

What’s so romantic about white supremacy? Why do white people get off on this kind of fantasy? The harder people insist that such iconography is merely “classic,” the clearer it becomes that what makes it “classic”—and what makes such classic iconography desirable—is precisely the promise of guilt-free white supremacy. But nostalgia for colonial Africa is exactly like nostalgia for Dixieland segregation and Jim Crow. When white people get married at a Southern plantation house, it is Gone With the Wind and its inherited racial hierarchy that they are emulating, a sense of classic romance that was predicated on subjugated black bodies. The same is true of the African safari, a white landscape where white people can travel in luxury to look at animals, while the only black bodies are seen and not heard, serving, docile. Staging a music video against that backdrop is not that different than if Swift had cast herself as Scarlet O’Hara and Scott Eastwood as Rhett Butler, or used Nazi imagery in a video about … something. But she would never do that. Those instances of white supremacy aren’t nearly so easy to enjoy; in the present moment, they hit too close to home.

So you go to Africa. Africa is timeless. Africa is classic. In Africa, you can turn back the clock. You can cast a few black people as porters, and leave them out of the shot. In Africa, you can make the collapse of colonial rule the backdrop for the collapse of a love affair. And then you collect your awards. And you donate to a conservation fund. Because you care.