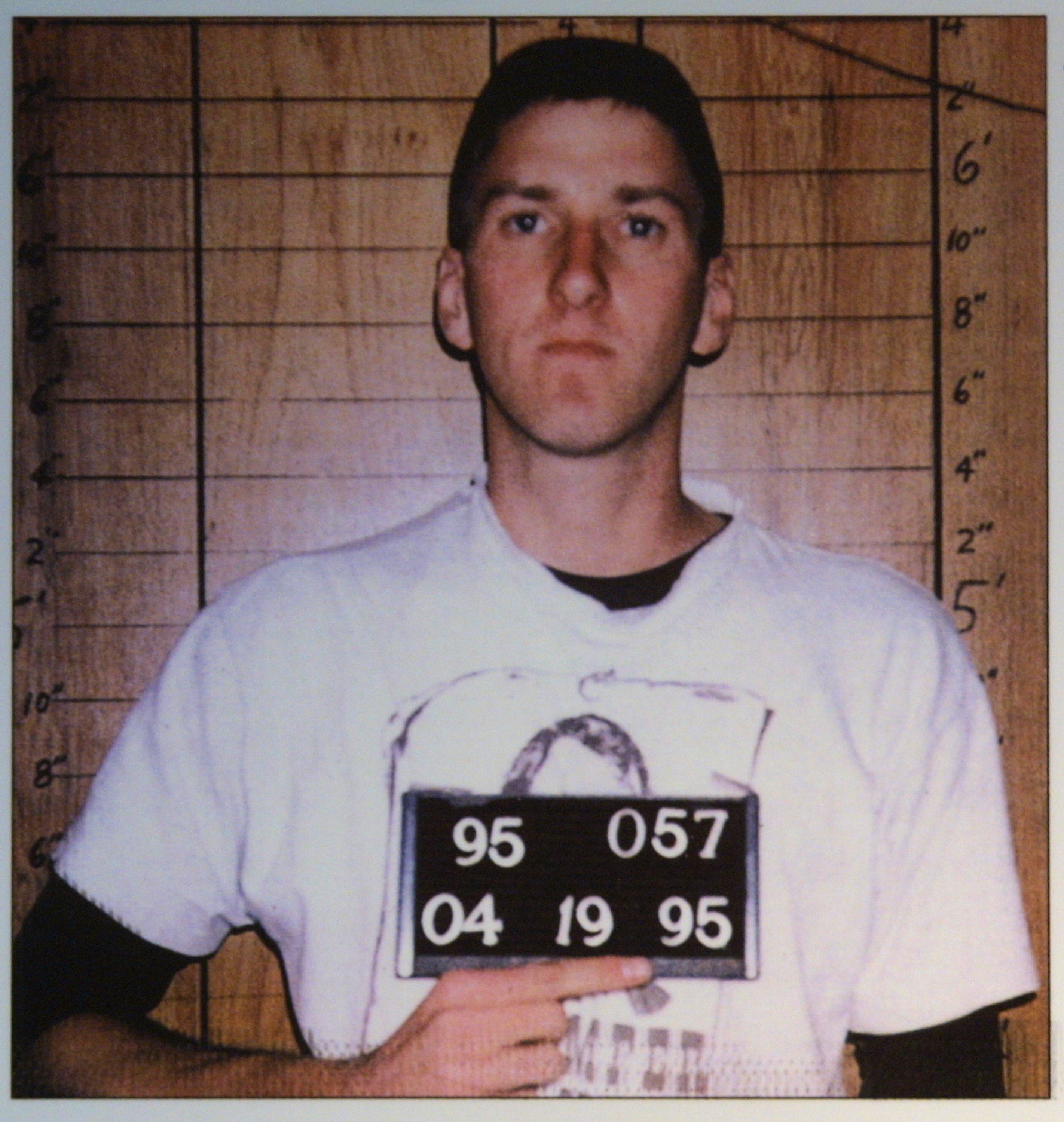

As a recent college graduate in 1995, Daryl Johnson took a road trip from Utah to Virginia where a job at the United States Army’s Counterintelligence Center (ACIC) at Fort Meade, Maryland, awaited him. On the way, he stopped in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, where, only months earlier, Timothy McVeigh, a U.S. Army veteran radicalized by anti-government rhetoric and interactions with members of right-wing militias, had killed 168 people with a truck bomb. Many had initially believed the bombing was a foreign terrorist attack, but Johnson, from the onset, had possessed a different theory. He had noted the attack had targeted a building housing Federal Bureau of Investigation and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) offices, and that the explosion happened on the two-year anniversary of a botched ATF raid on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, that resulted in over 80 deaths. It was a connection the FBI had also made, which ultimately resulted in the arrest of McVeigh and a handful of domestic co-conspirators shortly after the attack.

Johnson worked as an analyst at the ACIC from 1995 to 1999, where he coordinated with Military Intelligence units, Criminal Investigations Command investigators, the FBI, and the ATF to collect information on violent far-right extremist groups that posed a threat to the military. The reports coming in from across the country made Johnson realize the Army was facing a real threat in their own backyard. In Michigan, a militia plot to attack a National Guard post was uncovered and thwarted in 1995. Months later, also in Michigan, there was an anti-government militia that infiltrated the Fort Custer Army Training Center and plotted attacks on service members it considered “communists.” In Massachusetts, a militia, which included an army reservist, stole $100,000 worth of night vision goggles from a National Guard armory. The list went on, and the takeaway was clear: Far-right extremists were targeting the U.S. Army for recruits, sometimes from within the army’s own ranks.

Johnson’s work at the ACIC put him on the radar of a federal agency that, by 1999, had found itself on the frontline of the war against right-wing domestic terrorism: the ATF, and specifically its Violent Anti-Government Group (VAG) program. Though the FBI was (and still is) responsible for investigating the terrorist activities of right-wing extremists, the ATF was responsible for investigating the tools terrorists use: firearms, incendiary devices, and explosives. Johnson was coming on board at the end of one of the deadliest decades for right-wing terrorist attacks, and he was nearly alone on the team: Within a year, the one field agent on the VAG program was reassigned.

Because there has never been an established legal definition of “domestic terrorism,” investigations into the criminal activities of far-right extremists fall into a gray area of responsibility. Like the Department of Defense, the FBI and the ATF cannot investigate a private citizen for expressing their beliefs—as horrible as they might be. But the ATF can track firearms, incendiary devices, and explosives—the preferred methods of terrorism for right-wing extremists in the 1990s—putting those groups directly in the ATF’s crosshairs. It was ATF agents who investigated the events leading to a standoff with a veteran who was selling shotguns to neo-Nazis in Ruby Ridge, Idaho, and ATF agents who discovered that the head of the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas, was smuggling hand grenades and automatic weapons into his compound—two events that would galvanize McVeigh and the far right for decades to come. The ATF and the FBI’s mishandling of these incidents drew the criticism of conservative politicians in the ’90s who considered the investigations evidence of an overreaching federal government.

Then came 9/11. Investigations into right-wing extremism were sidelined by the rush to play catch up against al-Qaeda. The FBI gained new tools and the ability to track Muslims living in the U.S. Those who’d felt the FBI was out of line for conducting surveillance and wiretaps on anti-government and white supremacist groups after the Oklahoma City bombing welcomed expanded measures to investigate Muslims across America.

The sudden shift toward Islamic terrorism exacerbated a long-standing jurisdictional rivalry between the FBI and the ATF. Busts determined budgets, and in cases far beyond right-wing extremism the two branches jockeyed to close the most cases to increase their funding. Johnson described ATF agents and analysts dancing around the words “terrorism,” “plot,” or “attack” in reports shared with the FBI, as the Bureau would often scoop up those investigations and cut off the ATF.

“I shared way more information with the FBI than they ever did with me,” Johnson recalls, “the combination of limited resources, infighting, and the political minefield [of investigating right-wing extremism] meant investigations suffered.”

Investigating far-right extremists in the U.S. military might seem like a straightforward task. The Southern Poverty Law Center and Anti-Defamation League both keep a running database of active duty service members who participate in far-right extremism. Some service members make no effort to hide their white supremacist or anti-government rhetoric and conspiracy theories: According to a Military Times poll, one in four troops say they’ve seen evidence of white nationalism in the ranks. The SPLC has notified the Department of Defense on multiple occasions of evidence that soldiers, sailors, and Marines are active participants in neo-Nazi organizations and anti-government groups.

Yet time and time again nothing has happened; charges never materialize and service members aren’t discharged. Why?

(Photo: Getty Images)

Members of the U.S. military are held to a separate legal code than civilians: the Uniform Code of Military Justice. But just like it isn’t for their civilian counterparts, under the UCMJ, espousing racist or anti-government rhetoric is not in and of itself a crime. While the Department of Defense has criminalized membership in the KKK and other racist hate groups, as long as a soldier is not directly affiliated with these groups, espousing the same ideology that they promote isn’t technically criminal behavior for a service member.

The U.S. Army’s CID cannot investigate or recommend prosecution against a service member for espousing his or her beliefs. Army Regulation 195-2, paragraph a, subsection 2, line h contains this directive: “Information concerning purely political activities and personalities, or disorders in which no crime is indicated or suspected will not be collected, recorded, or reported by the USACIDC.”

Unless an additional crime is committed, soldiers cannot be investigated by the U.S. Army for being a white supremacist or anti-government extremist. According to an active duty CID investigator, even when a service member has committed a crime that warrants an investigation, military investigators can only look into affiliations with right-wing extremism as it pertains to the crime being investigated.

Moreover, just getting a CID, Naval Criminal Investigative Service, or Air Force Office of Special Investigations case opened against a right-wing extremist in the ranks is a long process. A unique feature of military criminal justice is that unit commanders have almost complete discretion over investigating, prosecuting, and adjudicating crimes committed by those under their command. Before a CID investigation is opened, the service member’s commander conducts an internal investigation, after which the commander determines whether or not the case warrants further investigation by CID.

This is part of the reason why a neo-Nazi ring at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, operated with relative impunity until two people were murdered, and why a publicly avowed neo-Nazi was able to serve in the U.S. Navy SEALs for multiple deployments in the early 2000s even after the SPLC alerted officials of his support of white supremacist groups.

According to the CID official, if commanders request further investigation, Department of Defense investigators across the military are mandatory reporters to the FBI’s e-Guardian program, a centralized collection point for any suspicious conduct that is analyzed by one of the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force offices.

The problem of relying on the discretion of military commanders to report white supremacist behavior is a reflection of the broader issue facing law-enforcement efforts to prevent right-wing terrorist attacks, according to Peter Singer, author and strategist at New America, a non-partisan think tank. “You have an ideology whose adherents have killed more Americans than ISIS has, and yet we don’t agree across all the different institutions across our society and government that it’s a problem and that it’s a problem of terrorism.”

While there is a small but established presence of radicalized active duty service members, it’s after leaving service that veterans are most likely to be targeted for recruitment into far-right extremist groups. For decades, the FBI has noted that veterans are specifically targeted for recruitment by white supremacist and anti-government groups for their military skills as well as for the aura of credibility that veterans bring to their agenda.

Right-wing extremists often disguise their ideology behind symbols of patriotism, and they can present an alluring lifestyle to veterans looking to find their place in civilian society again. Extremists celebrate the weapons and tactical skills veterans possess, and “training exercises” can recreate the experience of military operations.

(Photo: Daryl Johnson/Twitter)

Because right-wing extremist groups, like the Oath Keepers and Three Percenters, often are grounded in mainstream conservative political positions on issues like the Second Amendment, abortion, and states’ rights, they can initially present themselves as concerned citizens before exposing the veteran to more radical ideology. They target veterans for recruitment with reminders that they swore an oath to defend the U.S. Constitution against all threats, foreign and domestic—though it’s their understanding of what constitutes a domestic threat to the Constitution that places them in the realm of neo-Nazis, anti-government extremists, and conspiracy theorists.

Sometimes, veterans are used by right-wing extremists without their knowledge as in 2011, when an anti-government extremist group in Florida was reported to have been holding extrajudicial common law courts in an American Legion building, joining anti-government militias in Hannibal, New York, and Verde, Arizona, who also used American Legion halls for meetings.

Right-wing terrorism, like jihadism, does not happen in a vacuum. It’s facilitated by an ecosystem of radicalized people on the fringes of hyper-conservative politics.

“In our politics you’re politically rewarded for being tough on every form of terrorism, but one,” Singer says. “In the past, it’s been very difficult for law enforcement and the press to wrestle with this topic. There’s examples under prior administrations of people writing reports and their careers have been ended for it.”

In 2004, Johnson left the ATF to lead the newly founded Department of Homeland Security’s domestic terrorism team, where he worked extensively with the FBI and the ATF. In 2007, after Johnson held a meeting with the FBI about a recent inquiry from the U.S. Capitol Police Department about threats against Illinois Senator Barack Obama, he began collecting any reports he received on violent right-wing extremists, including those in the military, for a potential larger study. Johnson settled on a name for his side project: Gathering Storm.

A storm, indeed, was gathering. Barack Obama’s campaign in 2008 threw conservative America into a frenzy—the SPLC noted an 800 percent increase in the number of right-wing militia groups in the four years following his election—and activated numerous veterans in far-right movements. In July of 2008, a 58-year-old Army veteran killed two and injured seven others when he opened fire in a church in Tennessee; a letter found in his truck after the attack blames liberals, black people, and the LGBT community for his violence. In December of 2008, a U.S. Marine was arrested along with four others for attempted robbery, and a journal detailing his plans to assassinate Obama was discovered in his barracks room.

Johnson knew from history he needed to tread carefully when it came to describing right-wing extremism. A 1999 FBI report on extremists who might react violently to the new millennium, dubbed “Project Megiddo,” was leaked before publishing, and the backlash from conservative press outlets was severe. And as Johnson was finishing his report in 2009, the Missouri Information Analysis Center, an intelligence agency, released a report on the militia movement, in response to which conservatives immediately began accusing the state government of wanting to arrest anyone with conservative political views.

In April of 2009, Johnson sent his own report to a list of Joint Terrorism Task Forces, fusion centers, police departments, and federal agencies, and left work for the weekend. When he came into the office the following Monday, he noticed something odd. Requests and comments about his report were coming into the DHS from military officers who weren’t included on the distribution list. Johnson’s report had been leaked.

“When I came back to the office on Monday, it was all chaos,” Johnson recalls. “We were triaging complaints, responding to congressmen, writing up talking points, responding to [Freedom of Information Act] requests.”

The report would prove to be prophetic. One section declared, “lone wolves and small terrorist cells embracing violent rightwing extremist ideology are the most dangerous domestic terrorism threat in the United States.” A portion of the report detailed how immigration had become a rallying point for the spectrum of right-wing extremists: “DHS/I&A [Intelligence and Analysis] assesses that rightwing extremist groups’ frustration over a perceived lack of government action on illegal immigration has the potential to incite individuals or small groups toward violence.”

Notably, one section of the report described the increased threat of veterans being targeted for far-right extremism recruitment:

DHS/I&A assesses that rightwing extremists will attempt to recruit and radicalize returning veterans in order to exploit their skills and knowledge derived from military training and combat. These skills and knowledge have the potential to boost the capabilities of extremists—including lone wolves or small terrorist cells—to carry out violence. The willingness of a small percentage of military personnel to join extremist groups during the 1990s because they were disgruntled, disillusioned, or suffering from the psychological effects of war is being replicated today.

Less than a month after the report was released, a Florida National Guardsman killed two sheriffs deputies before being killed by police. According to his wife, he was angered by Obama’s election and had expressed interest in joining a local anti-government militia.

Even though the report’s analysis later proved accurate, the report, once leaked, was lambasted by conservatives. Future Speaker of the House John Boehner accused the Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano of attempting to label all conservatives “potential terrorists.” A conservative pundit called it an Obama-directed “hit piece.” Napolitano would eventually meet with heads of veterans groups to apologize and clarify that the DHS didn’t consider military veterans potential terrorists, even though the report never actually said it did.

Following the outrage, the DHS dismantled Johnson’s team, sending analysts to other desks. “They canceled our work, canceled our training, all of our reports were stopped,” he says. Johnson’s career as arguably one of the most experienced and knowledgeable analysts of domestic terrorism in America was over.

(Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

In 2017, President Donald Trump froze and revoked grant funding to a handful of initiatives aimed at community-based approaches to countering right-wing terrorism, all while awarding funding to groups targeting Muslim extremism in America. There are still no domestic terror laws in America, or even a federal definition of what constitutes domestic terrorism.

As long as efforts to counteract domestic terrorism go underfunded, the threat to America’s veterans of being targeted by right-wing extremists remains. If new veterans look to the president for guidance on where they can best contribute to their country as civilians, his Twitter account and public statements would suggest there’s an urgent lack of security on the U.S.–Mexico border and that large swaths of the federal government—specifically the FBI—cannot be trusted. These claims are echoed by conspiracy theorists, white supremacists, anti-government militias, and Christian Identity Extremists.

American right-wing extremist ideologies appear to be informing more right-wing terror attacks abroad, including the recent mass killing in Christchurch, New Zealand. Johnson thinks the increasing threat of right-wing terrorists is here to stay.

Despite new challenges, many problems—most especially the consistent focus on the threat of foreign terrorism at the expense of domestic investigations—remain the same as they were a decade ago.

In 2009, after the DHS dismantled his team, Johnson, too, was reassigned. Even though he had pioneered various efforts to track violent right-wing extremists, he was moved off the domestic beat: “They did a big restructuring over the summer [of 2009] and reassigned us to different topics,” Johnson says. “I got sent to cover al-Qaeda.”