There’s a disturbing pattern of missing and murdered indigenous women throughout North America. In 2015, a quarter of all murdered Canadian women were indigenous, and we’re less than 5 percent of the population. It can be difficult to tally the number of missing or assaulted indigenous women in North America, but, in the United States, the National Institute of Justice reports that over half of Native women have experienced sexual violence in their lifetime, and 38 percent were unable to receive victim services. These issues are closely linked: It seems that it’s easy to hurt Native women, and easy to make us disappear.

The issue is a personal one for me. I’ve seen families in states of emergency, searching for their loved ones and begging for authorities to act faster. I’ve heard families of a missing girl discuss their frustration with what they describe as impossible red tape. These people are part of an extended community of First Nations people where I’m from.

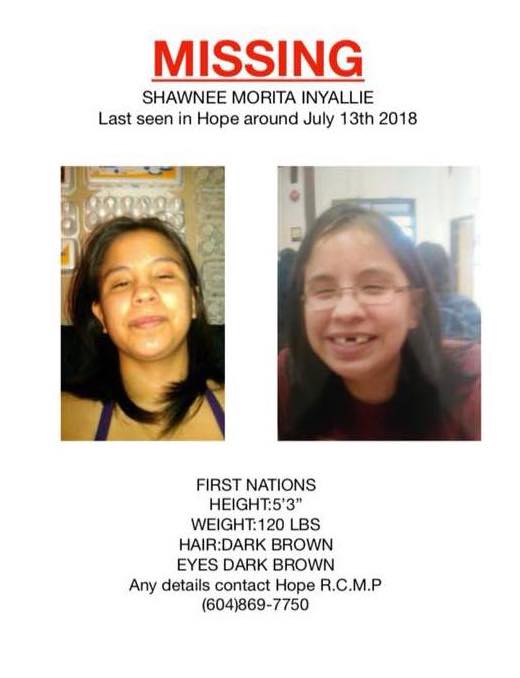

I lived most of my life on a small Indian reserve called Seabird Island in British Columbia, Canada. Next to that reserve is Chawathil First Nation, where many of my childhood friends live and work. The community is tight-knit, so when 29-year-old Chawathil community member Shawnee Morita Inyallie went missing a month ago, everyone I knew there was concerned.

Many people describe Shawnee as friendly, talkative, and and generous to everyone, even strangers. Shawnee is without a home and is known to walk the highways and hitchhike where she needs to go, which puts her in a vulnerable position. I contacted her aunt, Jeannie Kay-Moreno, who is a retired support worker and a current councilmember at Chawathil.

“At times it gets to be helpless. It’s a helpless feeling,” Kay-Moreno says of the search for her niece. “Fear creeps into your mind.”

According to Kay-Moreno, they haven’t found a solid lead so far. She says it’s hard to stay positive, though she’s effusive about her niece: “Shawnee has a very bubbly personality—very warm and welcoming. Even though her circumstances could be bleak, she had a positive way of being. She’s always smiling.”

A month is a long time for a young woman to be away from her family without an income or a home, and, each day, more of my friends from the communities close to me are sharing the missing persons poster that bears her likeness. Shawnee’s case has us once again discussing the problem of murdered and missing indigenous women. North America is not safe for indigenous women, and we need all the support we can get. The information and realities we’re faced with can be overwhelming: We see the missing posters and read the statistics about those who have disappeared and see how we are portrayed on television and in film, and we hope for something better. I wish we were safe. I wish we could live in peace, but I’ve never experienced a life without violence surrounding me somehow.

Speaking recently to the CBC, Shawnee’s mother said: “She is still out there somewhere, and I have no idea where. … Please, my daughter, wherever you are come home.”

(Photo: Terese Marie Mailhot)

I have reasons to worry that people might see a poster of a Native missing woman and dismiss it because of the negative stereotypes that people have fastened to us. In the comments sections of stories about missing Native women, I have seen men and women discuss our supposed alcohol abuse, or speculate about how a woman’s past might have invited her predicament—and I’ve seen crueler comments too. I believe there is a bias at work around this continued pattern of murdered and missing indigenous women, and throughout my life I’ve experienced too much of that bias from authorities to trust them. In this case, I wanted to do something more, so I put up a thousand-dollar reward for tips that will help Shawnee’s family and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police find her. Offering that reward was the first thing I did when I received money for my book, a little over a week after she’d gone missing. Success means being able to help the people I care about; I thought, what if I can help find one woman? What if I could put aside more money each year for more such rewards? How long will these women continue to disappear?

Many people from Shawnee’s community and beyond have shown up to search the highways and put up posters. Her mother, her aunts, and her cousins have worked together to visit camps for people without homes, asking residents for any clue as to her whereabouts. They are organizing and working with extraordinary strength during this time.

With each passing day, I hope I’ll be able to reward someone for finding her, and my deepest and most sincere hope is that Shawnee will appear herself, safe and smiling, and I’ll just hand her the money. Authorities don’t look out for Native women well enough, and that has hurt me for much of my life. Now, with Shawnee’s family pulling together with their community, I’ve decided we are not helpless—that we can cover more ground, and do more good, than any of us have been given credit for.