White guys are dying.

That’s the alarming takeaway from new research published in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, which shows that middle-aged, white, non-Hispanic Americans have been dying at a greater rate than ever before. It’s not that there’s been a sudden, apocalyptic die-off in white guys; according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, white men and women tend to have higher-than-average life expectancies than other ethnic groups in the United States, surpassed only by Hispanics. Instead, the PNAS study shows that the mortality rate for white, middle-aged men is well above that of other advanced countries like France and Germany—and that it’s increased domestically over the last decade while declining everywhere else.

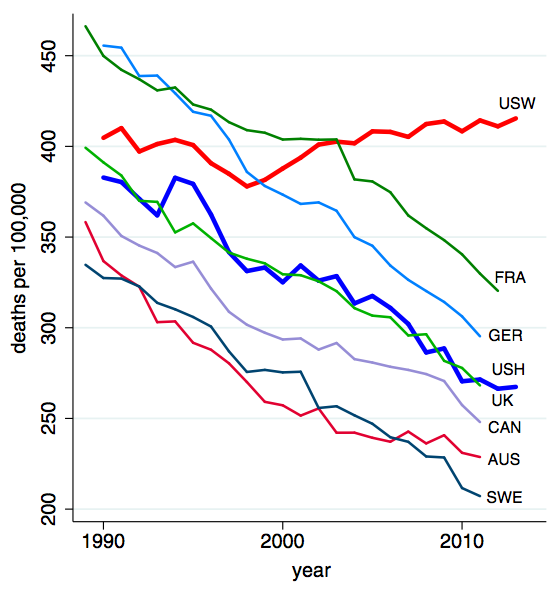

“Between 1978 to 1998, the mortality rate for U.S. whites aged 45 to 54 fell by 2 percent per year on average, which matched the average rate of decline in the six countries shown, and the average over all other industrialized countries,” the researchers, led by Nobel economics laureate Angus Deaton, write. “After 1998, other rich countries’ mortality rates continued to decline by 2 percent a year. In contrast, U.S. white non-Hispanic mortality rose by half a percent a year. No other rich country saw a similar turnaround.”

This a sobering trend encompasses “half a million deaths” between 1999 and 2013, according to Deaton, on par with the number of people killed by the AIDS crisis that began in the 1980s. “Such a situation is unprecedented in the annals of public health among developed nations, with the exception of Russian males in the 1990s after the fall of the USSR,” observes Dr. Gill Ross of the American Council on Science and Health on the organization’s website. Its significance becomes even more evident when you look at this highly trafficked chart:

So what’s causing this surge in deaths among white men? There’s dysfunction afoot. According to Case and Deaton’s data, this sudden jump is centered on white men with a high school degree or less; mortality rates spiked by 134 deaths per 100,000 people between 1999 and 2013 for men in this group, while rates fell by 57 deaths per 100,000 for those with a college degree or more. And, as the American Prospect‘s Paul Starr observes, most deaths arose from some level of self-harm, either indirectly (drug overdoses) or directly (suicide). Mental illness rose among men without high school degrees too; Starr observes “significant increases as well in the percentages reporting poor health, chronic pain, and difficulties with such activities as walking a quarter mile, climbing ten steps, and socializing with others…. The percentage reporting themselves unable to work doubled.”

Almost three-quarters of the eight million jobs lost during the Great Recession of 2008 belonged to men—jobs that, in manufacturing, won’t return any time soon.

The most obvious explanation for this alarming uptick in self-harm, from looking at Deaton and Case’s report, is trauma—some level of massive social, political, or economic disruption that’s thrown an entire sector of American society into a tailspin. It’s a classic concept straight out of Émile Durkheim’s groundbreaking 1897 book Suicide, which attempted to examine the relationship between private troubles (suicide) and public dysfunction. Massive disruption in the prevailing social order leads to anomie, “a condition in which society provides little moral guidance to individuals,” Durkheim wrote, as the bonds between society and the individual begin to break down. Economic turbulence, like massive layoffs, or a political upheaval can disrupt the institutions that provide some sense of social solidarity for the average individual; in modernity, that’s the workplace rather than “mechanical” sources of solidarity, like the family or church. When the individual doesn’t feel a connection to the broader society, he can spiral into poor health, addiction, and even suicide.

The methodology and logic of Durkheim’s infamous work on suicide has been widely debated and critiqued over the last century, but its lessons on the mediating role on solidarity seem salient here. With the rise in white mortality beginning around 2001, it’s safe to assume that the economic turbulence wrought by 9/11 and the intervening political chaos of the War on Terror (a correlation born out by Bureau of Labor Statistics’ unemployment data) seriously disrupted many of the regulating institutions of American life. Imagine being suddenly laid off and going stir crazy alone in your apartment without the everyday routine of a commute and your work and the daily joy of your social connections with friends and colleagues. Now imagine that listlessness, that anxiety, felt across every aspect of your life. These tensions are felt more acutely by lower- and middle-class workers; after all, almost three-quarters of the eight million jobs lost during the Great Recession of 2008 belonged to men—jobs that, in manufacturing, won’t return anytime soon.

But if we’re just talking about economic dislocation, why are we so worried about white men? After all, the mortality rate among blacks is significantly higher than among whites, as is the unemployment rate. Even as the U.S. economy has bounced back, the majority of those gains have flowed to white Americans, who, on average, have a net worth 13 times that of their black neighbors. Hell, recent research shows that just living as a black person in the U.S. is traumatic, as the specter of racism creates a daily cycle of anxiety and stress. So why is that the white males are so especially traumatized by the tumult of the U.S. political economy?

I suspect that the turmoil of the last 15 years has left men in a political and social limbo, as the institutions they traditionally dominated—jobs, high office, even the public commons of the Internet—become increasingly threatened by the political and economic changes washing over the country.

As the Atlantic‘s Hanna Rosin wrote in her now-famous piece, “The End of Men,” women are excelling in education and in the job market more than ever before:

Earlier this year, for the first time in American history, the balance of the workforce tipped toward women, who now hold a majority of the nation’s jobs. The working class, which has long defined our notions of masculinity, is slowly turning into a matriarchy, with men increasingly absent from the home and women making all the decisions. Women dominate today’s colleges and professional schools—for every two men who will receive a B.A. this year, three women will do the same. Of the 15 job categories projected to grow the most in the next decade in the U.S., all but two are occupied primarily by women. Indeed, the U.S. economy is in some ways becoming a kind of traveling sisterhood: upper-class women leave home and enter the workforce, creating domestic jobs for other women to fill.

Men have been getting left behind in American life for years; for poor whites who lacked much economic power in the first place, the ascendency of women and minorities is particularly alarming (just look at the racial anxiety of the Tea Party.) For the latter two, economic turmoil is just another batch of nonsense to deal with.

Let’s be real: A white man can walk down the street in the U.S. without constantly worrying about being shot or raped. When it comes to the political hierarchies sown by 200 years of American tradition, it’s hard to believe the “war on whites” nonsense. Rather, the anomie of the modern American man is a relative experience; after centuries at the center of the universe, he finds himself no longer even a part of it because of his gender or race, no longer insulated by his privilege and, for the first time, having to deal with a lack of social power that everyone else on the planet has had to deal with.

Starr puts it best in the American Prospect: “The role of suicide, drugs, and alcohol in the white midlife mortality reversal is a signal of heightened desperation among a population in measurable decline…. The phenomenon Case and Deaton have identified suggests a dire collapse of hope.” If there’s one trend to take away from the sudden uptick in self-harm among middle-aged white Americans, it’s this: The bigger you are, the harder you fall.