FX and Disney Channel are on track to make television history. On Wednesday, showrunner Ryan Murphy revealed that his upcoming FX ’80s drama, Pose, would assemble the largest cast of transgender actors—five—ever assembled in a single series. Not long after, the Disney Channel announced that a main character on one of its series—Cyrus on Andi Mack—will come out as gay, a Disney first. Though shows like Transparent and Orange Is the New Black have given us iconic queer characters in the last few years, these new narratives are poised to put these still-underrepresented identities on center stage.

Both LGBT children’s characters and adult transgender characters don’t see much screen time compared with other queer roles on TV (an already small pool). Transgender characters were the least prevalent LGBT roles in the 2016–17 television season, constituting 4 percent of queer characters in broadcast and cable networks, and 11 percent on streaming platforms. And though children’s programs have a long history of alluding to non-heterosexuality, they’ve been slow to take their characters out of the closet. Cartoon Network and Nickelodeon’s first married gay couples arrived in 2016; the Disney Channel showed its first gay kiss last May.

FX and Disney Channel’s decisions represent a renewed investment in their queer viewership. But the inclusion of minority characters in mainstream television can also bring benefits for viewers who don’t identify with them—by broadening their minds.

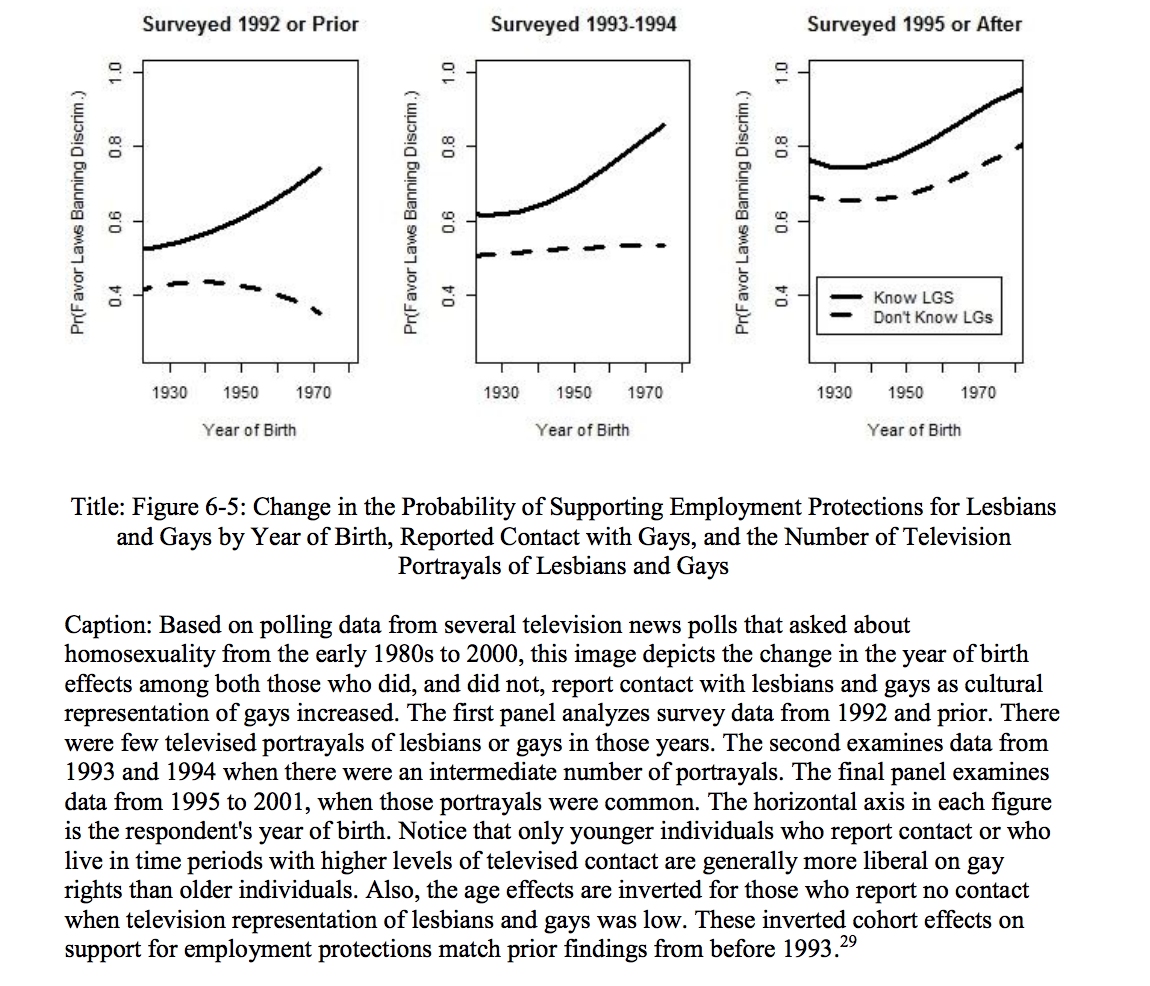

Plots involving LGBT characters can improve social tolerance, according to research from the forthcoming book The Path to Gay Rights. Author Jeremiah Garretson, an assistant professor of political science at California State University–East Bay, analyzed six TV news polls since the mid-1980s that measured participants’ direct contact with gay people and their support for employment protections for gay and lesbian people. He compared those findings with the number of lesbian, gay, and bisexual television characters active in the years participants were polled. The results, he says, “illustrate that, as exposure to lesbians and gays increase, either interpersonally or through television, the probability of supporting job protections for lesbians and gays goes up by birth year.” Among the cohort of young people measured, contact with gay people, and gay characters on TV predicted support for gay and lesbian employment protections.

But research has found that not all nuanced LGBT roles are created equal: Minority characters appear to change minds more when they are returning characters instead of guest appearances. In a study he conducted in 2013, Garretson found that frequent TV viewers show higher levels of social tolerance when a greater number of minority characters have recurring roles.

And in a study published in 1999, a Rutgers University marketing professor found that frequent soap opera viewers tended to be more distrustful of people, and insecure about the fate of their marriage, than those who only watched once in a while. It stands to reason, then, that if viewers are exposed to five transgender characters in Pose, and a returning, major gay character in Andi Mack, they might experience some of television’s attitude-changing effects.

Some minority characters, too, can do more harm than good when they rely on stereotypes. In 1997, a researcher at Western Carolina University found that stereotypical depictions of African-American characters in comedy skits increased the level of guilt that students assigned to an African-American student accused of assault, but not a white student accused of the same crime.

In this regard, FX and Disney have some work to do. Archetypes that show up in every one of Murphy’s shows (the Hot Gay Guy, the Sassy Black Girl) are the stuff of Vulture listicles. And Disney has a bad track record of giving villains like Aladdin‘s Jefar and The Little Mermaid‘s Ursula stereotypically queer qualities. The representation milestones these channels announced this week are important—but FX and Disney will have to work hard to really make a difference.