New York City Yemeni American convenience store owners are refusing to sell copies of the New York Post in response to a front page image attacking Representative Ilhan Omar (D-Minnesota) for comments she made about 9/11. The boycott comes amid growing calls for similar demonstrations against right-wing media, and questions over how—and whether—media boycotts work or if they serve to strengthen the partisan positioning of those they target.

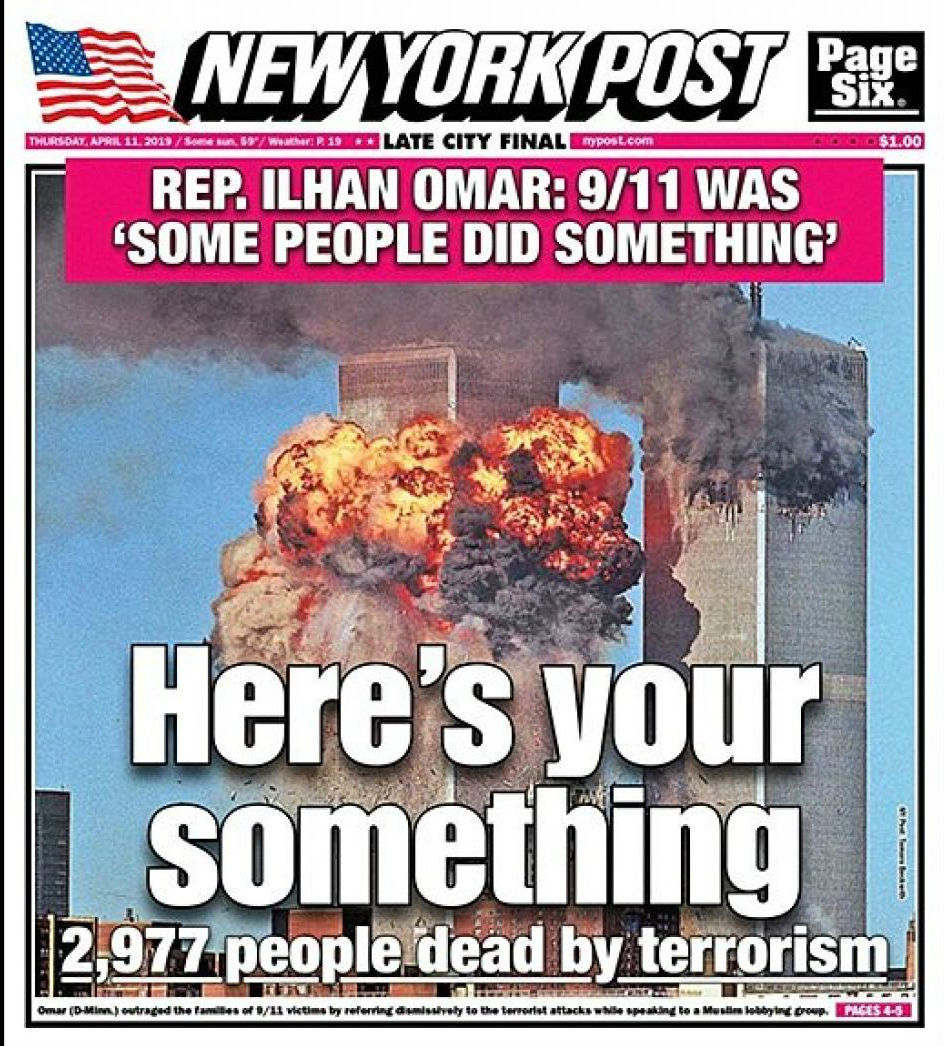

The cover of the April 11th edition of the New York Post featured an image of the smoldering World Trade Center, reading “Rep. Ilhan Omar: 9/11 Was ‘Some People Did Something'” and “Here’s Your Something, 2,977 People Dead by Terrorism.”

(Photo: New York Post)

The paper took a partial quote and transposed it over an image of the attack, seeming to associate Omar with it, observers charged. At a Council on American Islamic Relations banquet last month—at which Omar was targeted by what appeared to have been a white supremacist bomb threat—Omar said, “CAIR was founded after 9/11 because they recognized that some people did something and that all of us were starting to lose access to our civil liberties.”

Boycott organizers saw the Post‘s coverage as the latest flashpoint in right-wing media’s ongoing attacks on Americans of Muslim faith.

“The Islamophobic coverage of Representative Omar and the endangerment of her life and the lives of American Muslims nationally is what prompted our members to take this action,” says Debbie Almontaser, board secretary of boycott organizer the Yemeni American Merchants Association. “The response was welcomed [by storeowners] with joy!”

YAMA, together with CAIR-NY and other community groups, issued a press release demanding, among other things, that the New York Post publicly apologize, fire Editor-in-Chief Stephen Lynch, and stop publishing “cheap and sensational tabloids that undermine national unity and entice violence and hate for the sole purpose of circulation and sales.”

Almontaser says that the boycott, launched last week, will last 30 days. “We are going to give the New York Post a chance to respond to our demands,” she says.

New York Post staff did not respond to Pacific Standard’s request for comment.

The community group behind the boycott was founded in 2017, after President Donald Trump’s inauguration and subsequent attempts to ban those from various Muslim-majority nations from traveling to the United States, in-keeping with campaign trail promises.

“YAMA was birthed out of the Muslim Ban resistance. Our members now understand that they need to be civically engaged to challenge policies from the White House to school house,” Almontaser says.

The Yemeni American merchants’ New York Post boycott is not the first of its kind under the Trump administration. Since President Donald Trump’s inauguration, organizers have issued repeated calls to boycott right-wing media and its sponsors over racist, Islamophobic, anti-immigrant, and misogynistic remarks—which the groups charge amount to an incitement to violence.

There has been some question among organizers over what form such boycotts should take and their scope. Some organizers have called to target specific Fox News programs following individual statements by the outlet’s anchors. Organizers of website FoxNewsAdvertisers.com and the associated twitter account, @ConsumerFX, have gone a step further, compiling the details of Fox News advertisers and publicizing them, enabling the companies’ patrons to withhold their business.

At present, there has been no concerted effort to defund the various right-wing media outlets accused of engaging in hate-mongering by divesting support and patronage from its advertisers. What’s more, some boycotts may actually buoy right-wing media by reinforcing their conservative credentials to their audiences, experts say.

“The boycotts against Fox, Breitbart, and other right-wing media outlets are a bit abnormal for a one major reason,” says Brayden King, a professor of management and organizations at Northwestern University who has researched the efficacy of boycotts. “In some ways the boycotts, which are typically initiated by progressive or left-leaning activists, actually reinforce the reputation these media companies have tried to create for themselves. Liberal boycotts of right-leaning media may actually be good for these companies’ reputations.”

Experts do believe, however, there is still some room for liberal boycotts of right-wing media to succeed, particularly if targeted at advertisers. “Certain boycotts have been effective at driving away advertisers: I’m thinking of the boycott of O’Reilly, for example,” King says. “Boycotts that hurt advertising revenue seem to be more effective, regardless of their long-term consequences on the media company’s reputation.”

Some efforts have sought to target a broad array of right-wing outlets but have yet to successfully launch. James Kosur, founder of political news outlet HillReporter, told Pacific Standard late last year that he was working with developers on Web browser extensions to help users determine whether they are about to purchase goods or services from companies that sponsor news organizations like Fox and Breitbart. The project has since met with logistical challenges, Kosur says, and “for now is dead in the water.”

“If a new developer came forward and wanted to try their hand at the development, I would welcome it, but at this point, there was sadly a lot of spinning of wheels and no forward motion,” Kosur adds.

Where efforts to directly target advertisers may fail, a boycott’s success is largely contingent on the attention it generates. “Bottom line, the more media attention a boycott gets, the more likely it is that the boycotters will get what they want from a company,” King says. “Companies don’t like bad press, and boycotts tend to create this for companies. A boycotted company is most likely to concede if it senses that a concession will put an end to the negative spotlight the boycott has cast on them.”

For YAMA, that means it will become important for the boycott to move beyond convenience stores and to the general public. The organization has several hundred members and has sent out over 1,000 posters announcing the action that are posted across the city’s five boroughs. Almontaser says the boycott is spreading beyond the Yemeni American business community. “We have allies from all walks of life standing in solidarity with us and supporting our efforts. We have NYC residents asking for posters to post on their windows,” she says.