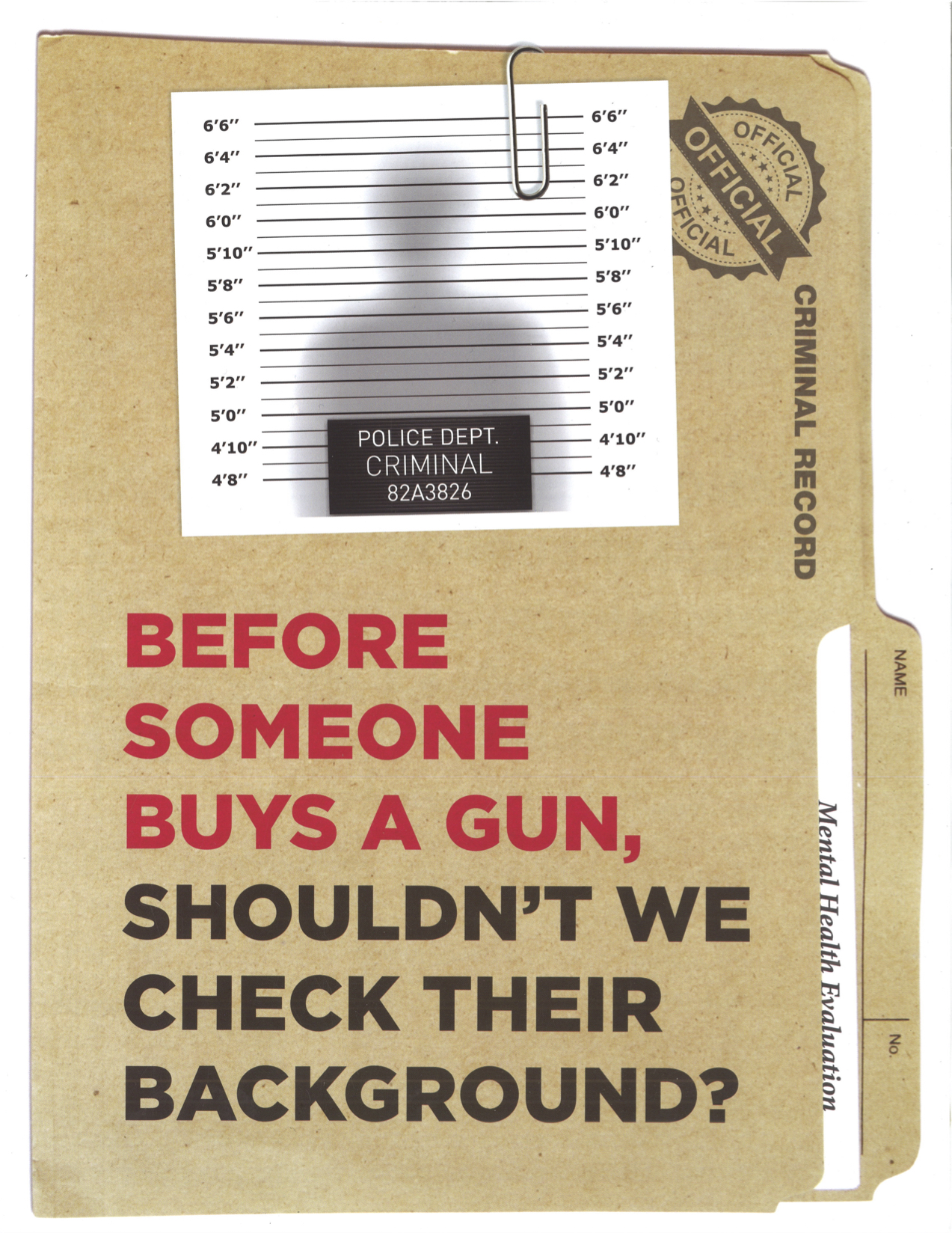

In the week before the mid-term elections, a slick political flyer arrived in my mailbox from the advocacy group Everytown for Gun Safety. The front shows an image of a manila folder designed to look like a police file. In red and black letters it reads, “Before someone buys a gun, shouldn’t we check their background?” The folder reads, “Criminal Record,” and, under the tab, we can see the words “mental health evaluation” peeking out. On the inside, the document endorses the local Democratic candidate for the Minnesota state house against incumbent Republican Randy Jessup, on the grounds that Jessup would allow “violent criminals” and people “prohibited from buying guns due to mental illness” to purchase firearms.

(Photo: David M. Perry)

The implication of the ad is that violently crazy people are getting guns thanks to Republicans. While I support universal background checks and other common-sense gun control laws—and would even be willing to see the Second Amendment repealed if right-wing judges keep using it to block even the most modest gun-control measures—the Everytown ad is just wrong. This pattern of linking mental illness to gun violence is misleading on the facts, will exacerbate stigma against people with mental illness, and won’t particularly work to stop the proliferation of guns in this country.

In fact, mental illness does not correlate with rising gun violence. A 2015 meta-study found:

Mass shootings represent statistical aberrations that reveal more about particularly horrible instances than they do about population-level events. Basing gun crime-prevention efforts on the mental health histories of mass shooters risks building “common evidence” from “uncommon things.” Such an approach thereby loses the opportunity to build common evidence from common things—such as substance abuse, domestic violence, availability of firearms, suicidality, social networks, economic stress, and other factors.

In other words, the biggest red flags for violence are access to firearms and domestic violence. Mental illness can, uncommonly, be a factor in mass shootings, but, as s.e. smith writes for The Nation, the biggest gun-related risk for people with mental illness isn’t murder; it’s suicide. The best research consistently emphasizes that the presence of mental illness is not a strong predictor of violence against others.

Experts in the field, like Bethany Lilly of the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, are tired of seeing mental illness stigmatized in connection to guns. After the 2017 Texas church massacre, Lilly told NPR: “There is no real connection between an individual with a mental health diagnosis and mass shootings. That connection, according to all experts, doesn’t exist.”

Writing via email after I sent her a photo of the Everytown flyer, Lilly says: “These kind of archaic, crass scare tactics not only disregard the decades of evidence we have about the connection between mental health and gun violence, but also increase stigma and discourage people from seeking help.”

Lilly rejects any attempt to “scapegoat people with mental-health needs” in the debate around gun violence, specifically citing “President Trump’s completely unconscionable proposal to lock up everyone with a mental-health diagnosis” as a dangerous example of this tendency. “We would expect better from all organizations, especially given the extensive public debate that we have had for the past several years about this issue,” she says.

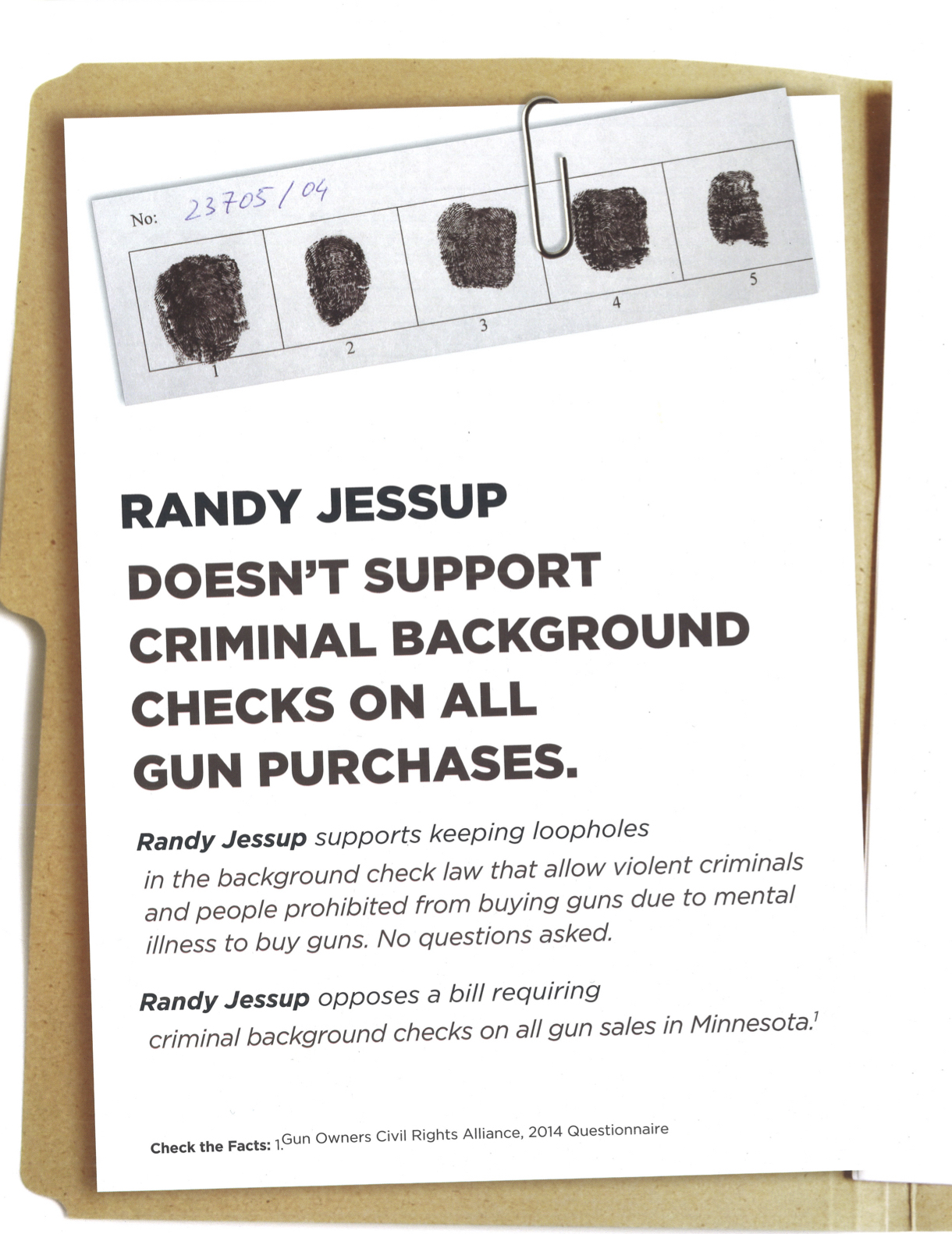

Over email, Adam Sege, the press secretary for Everytown, says that his organization is only targeting a narrow loophole that allows firearm purchases by people who are otherwise prohibited by federal law—”people with felony convictions, most domestic abusers, and people prohibited by mental illness—a limited group of people that includes people involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital or found to be a danger to themselves or others.” Everytown’s work in Minnesota has ramped up after the state got close to closing this loophole following the school shooting in Parkland, Florida, before ultimately falling short.

(Photo: David M. Perry)

Sege did not answer questions about the ways that this mailer seems to clearly promote a general mental-health stigma as a means to persuade voters.

I do not plan to vote for Jessup and have given both time and money to his opponent, Kelly Moller. Still, although Jessup has not been forthright in his position on universal background checks, he tells me by phone that he would now support a bill that would require someone making a private sale, whether at gun shows or elsewhere, to verify the purchaser has a “permit to purchase or concealed carry permit,” both of which require federal and state background checks. Moller, similarly, tells me that she would support both the universal background checks and the “red flag” bills that were introduced last session.

Everytown’s flyering campaign is part of a far-too-common pattern that crosses party lines. Too many groups use stigma and fear of mental illness as a wedge to win votes. The National Rifle Association, and the pundits and politicians who follow its lead, consistently cite mental illness in the aftermath of mass shootings, rather than zeroing in on better predictors of gun violence, like a history of domestic violence and the presence of firearms in the home. This campaign from Everytown, I fear, plays right into the NRA’s hands. It might defeat a particular politician, but it won’t stop gun violence. Even worse, it’ll teach people with mental-health needs to hide them, to stay closeted, and to avoid seeking help. That’s bad for public health and the cause of gun control, and it’s certainly bad for people with mental illness.