When Amanda Y. Feliciano Bonilla was growing up, she never imagined leaving her home island of Puerto Rico. Raised in what she calls “the projects” of Guaynabo, a low-income area surrounded by wealth, Bonilla takes pride in the person she’s become and in the community she calls home. Unfortunately, she says, she’ll likely have to leave the island in pursuit of her career.

“I don’t plan on moving in the short-term,” Bonilla says in Spanish. “But, honestly, with what I’m studying, in Puerto Rico there are no jobs for it here.”

Bonilla, age 24, studied social-cultural anthropology at the University of Puerto Rico–Río Piedras. She and her friend Gabriela Estrada Cepeda now manage an AmeriCorps booth at a health fair in Loíza, Puerto Rico, working for a project that aims to create community waste management plans for natural disasters. Both women feel as though the next few months of finishing school and applying for jobs are all that stands between them and a large decision: to stay or leave?

Cepeda, unlike Bonilla, wasn’t raised on the island. Growing up, her one constant was change—her father worked for the United States military, and, like many military families, they moved around the U.S. a lot. But, Cepeda says, “my cultural identity is from here and my values and my traditions are from here.” Nonetheless, as a 22-year-old pursuing her master’s degree in counseling psychology, she can’t see any future in which she stays in Puerto Rico as a young person.

(Photo: Rita Oceguera/Medill)

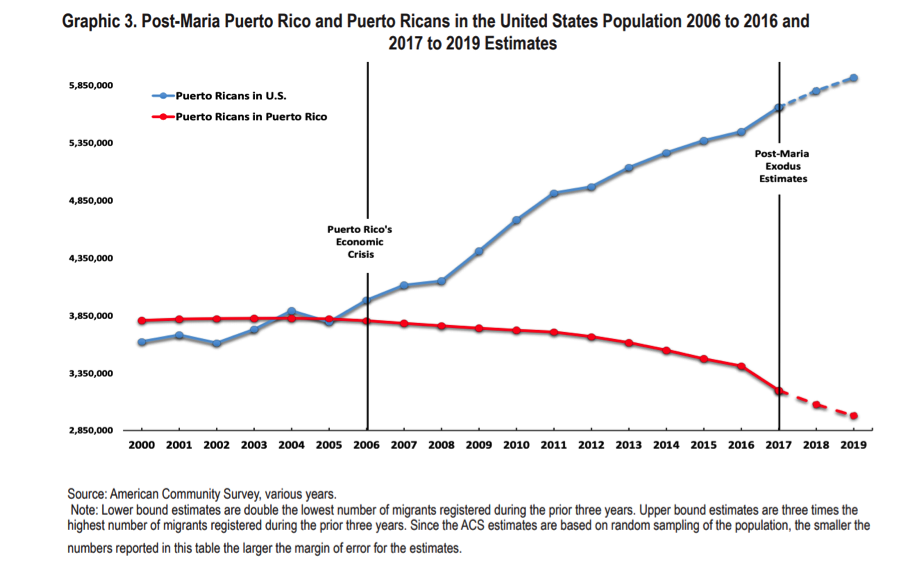

Puerto Rico lost nearly 8 percent of its population in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Maria, but the disaster alone did not decimate the island’s population. Over the past decade, many Millennials have left the island in droves seeking opportunities elsewhere, searching for jobs the island cannot supply. But some young Puerto Ricans have decided to stay. This internal struggle—to stay or to leave—sits at the center of the minds of young Puerto Ricans and drives social divisions in the island they call home.

A strong bond to their families, the island, and its customs and food makes following their career to the states an excruciating option for many youths on the island. Bonilla and Cepeda discuss the choice often.

On a February day as they chew over the topic again, Bonilla and Cepeda groan and laugh in exasperation.

“I at least have hope that if I go, it’s the last resort,” Bonilla says. “La última opción.”

The Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College estimates that, by the end of 2019, Puerto Rico may lose up to 470,000 residents from its 2017 population, or about 14 percent of the island’s population. The estimate for college-age youth (18 to 24 years old) leaving the island in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria ranges from 17,000 to nearly 33,000.

Though the hurricane did cause a massive shift in Puerto Rico’s population, Cepeda sees it simply as a turning point in an ongoing exodus among people her age.

“It’s like one of those plot charts we used to use for stories in literature class,” Cepeda says, and angles her arm to show a gradual upward slope. “The action was going up, and up, and up, until Maria.” She shoots her hand above her head. “But then Maria kinda just set it off, like everywhere.”

On the macro level, Cepeda has it right. Maria did set off a mass flight of people of all ages, but the social—and, more specifically, economic—reasons for leaving the island had been intensifying quietly for years.

Young Puerto Ricans have more than just career and family to consider: The island’s massive accrual of debt now rests on their shoulders. Puerto Rico has amassed a total of $122 billion in debt and pension obligations, wracked up as investors stockpiled high-risk bonds issued by the government.

Puerto Rico began to accrue massive amounts of debt in the late 1990s. The island used to be a tax haven for big businesses, and companies flocked to it. But when tax breaks phased out and fully ended in 2006, huge businesses left the island, destroying thousands of jobs, reducing tax revenue, and decimating the territory’s economy in the process. The federal government has exacerbated the issue through laws that make it harder for Puerto Rico to take control of its finances and economy. And since Puerto Rico is considered a territory and not a state, it has little say in how it is governed from Washington, D.C.

The island’s total debt now averages to $35,883 per resident—including children.

With these numbers, Puerto Rico simply cannot pay back what it owes. The island can’t apply for bankruptcy either. Because of a 1984 U.S. law, only cities—not states—can apply for bankruptcy. Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory, is neither, but the U.S. government has not made an exception. This leaves the Puerto Rican population to shoulder much of the island’s debt. In the face of the crisis, the unemployment rate now hovers around 8 to 9 percent, about double the U.S. national rate.

A new plan under COFINA, a government-owned corporation of Puerto Rico that issues government bonds, will restructure the island’s debt, giving the government and its people 40 years to pay back $3.23 billion. But as increasing numbers of Puerto Ricans leave, the island is losing a large portion of its tax base and potential bond holders.

In another effort to pay back the debt, the government is instituting austerity measures including cutting services and closing schools. As many residents see it, that means the bondholders are taking money directly out of Puerto Ricans’ pockets. “All the young people are going to carry this debt,” Bonilla says. “My children are going to end up paying it.”

The debt is a major factor in Oscar Ojeda’s deliberations about his future. A recent graduate of the University of Puerto Rico–Mayaguez, and a highly motivated student, Ojeda studied industrial microbiology as an undergraduate but still wants to pursue a higher degree in the U.S. or in Europe.

“I hate the debt,” Ojeda says. “Forty years is a long time to pay off something that isn’t our fault.”

Ojeda eventually wants to come back to Puerto Rico so that he can use the skills he gains in graduate school to better his community.

(Photo: Bill Healy/Medill)

“I get where they’re coming from, you know,” Ojeda says about people who choose to leave for good. “Taking that decision to move, it is not always the easiest. If it’s a matter of stay or go, it’s hard because, in a way, they’re economically incentivizing for you to go.”

Some feel like the government has created an ultimatum to either leave for a good job, or stay and risk not realizing the full earning potential that a higher degree offers.

Resentment swirls around that decision, and around 2016, a defiant hashtag cropped up on social media. #YoNoMeQuito, or “I won’t give up,” has since represented the feelings of many Puerto Ricans who want to stay on the island no matter what.

“So it’s like shaming the people who do leave,” Cepeda says. “That’s why I don’t really talk about it with people.”

For teens Jose Joel Cordero Hernandez, Ian Xavier Cora Maurás, and Luis A. Nieves Flores, leaving their home would mean abandoning all the work and activism they’ve done to improve their community.

The boys live near, and volunteer in, a community called El Coquí on the southeast side of the island. Hurricane Maria made landfall about 30 miles away, and it hit the poor rural community hard.*

The community lost electricity for weeks, but community members rallied around Coquí Solar, a volunteer organization focused on making solar energy accessible for local residents.

Hernandez, Maurás, and Flores volunteer with the organization in the hopes of turning El Coquí into a sustainable solar-powered community. El Coquí has long suffered the health effects of a nearby coal plant that stores a five-story pile of dry coal ash on-site. The coal ash, exposed to wind that whips through the town, covers every inch of El Coquí.

(Photo: Katie Rice/Medill)

The three teens’ passion for activism and connection to El Coquí makes it difficult to leave.

“We don’t want to go to university,” they say in Spanish. “When people go, they leave for good.”

A college education isn’t necessary to change one’s community—these boys are doing it at age 17. But the demoralizing cycle of “brain drain” often hits rural communities the hardest, and creates tension between those seeking higher education and those who are highly motivated but don’t see college as an imperative.

Carmen M. de Jesús Tirado, another volunteer at Coquí Solar, says it feels like people are deserting her hometown.

“They either go to another pueblo or to the United States to find work, but there is work to do right here,” Tirado says in Spanish.

As thousands of Millennials leave the island, some up-and-coming teen leaders of Puerto Rico might decide to reverse that narrative.

“I want to stay on the island because I want to make a change here,” Hernandez says. “I want my country to change. I want my country to not be contaminated any more than it already is. I want my country to be the country that all of us love. I was raised here in El Coquí, and there are a lot of people here who need my help.”

*Update—May 1st, 2019: A previous version of this article misidentified El Coquí as on the southwest side of the island.