One fateful night in the year 2000—long before the world would begin paying serious attention to his ideas—Matt Bowden met Kristi Kennedy in an Auckland, New Zealand, strip club. He was a 29-year- old raver and sometime rock musician who wore big leather boots and stovepipe pants. She was a Penthouse Pet who was wearing nothing. For both of them, it was love at first sight.

“It was one of those moments where time just stopped,” Kristi recalls. “I was dancing up on stage. This light shined down upon this man as he was walking into the room. He was looking at me with this big Cheshire grin and this bright green shirt and this blond ruffled hair.” Bowden was similarly smitten, and the two quickly became a couple. There was just one problem: meth.

Kristi was an intravenous methamphetamine user. Bowden was no teetotaler himself—he frequently snorted amphetamines during all-night raves—but he knew, as anyone familiar with drugs would, that there was a world of difference between his habit and hers. Shooting meth is a far more potent and addictive means of delivery, and carries a much higher risk of overdose. So he laid down an ultimatum that was, admittedly, not all that well thought out: He said that if she didn’t stop shooting up, he’d start. Kennedy handed him a needle. “He very gallantly dove in the deep end with me,” she says.

Perhaps the most perverse thing about the rise of legal highs is that, in a scenario that is the direct opposite of what Matt Bowden was trying to engineer in New Zealand, these new, easy-to-acquire drugs are often more dangerous than the illegal drugs that they copy.

For Matt, Kristi, and their social circle, the deep end would prove to be pretty deep indeed. New Zealand in those years was descending into a major methamphetamine epidemic. The formerly mellow Auckland dance club scene was becoming a quagmire of lost jobs and paranoia as more and more people began shooting and smoking meth. Casualties mounted.

One friend of Bowden’s died in a meth lab explosion. Another crashed through a glass door at a party and, believing himself invincible, fatally impaled himself with a samurai sword. In 2001, a cousin of Bowden’s became the third New Zealander to fatally overdose on MDMA (ecstasy), another drug often taken by the same ravers who liked to dance all night on meth.

Bowden was devastated by these events, and he could see his own life spinning out of control, too. Unique among his friends, however, Bowden thought he might know a way out of the downward spiral.

For a time in the late 1990s, Bowden had worked in the “herbal highs” business—developing and selling products similar to Red Bull, as well as some containing ephedrine, the active ingredient in the now banned performance-enhancing stimulant ephedra. In part to look for new products, and in part out of a personal fascination with drugs, Bowden had trained informally with a neuropharmacologist. And while perusing the scientific literature, he had come upon a drug called benzylpiperazine (BZP).

Developed as an antidepressant in the 1970s, BZP had failed clinical trials because it was an upper that was attractive to stimulant addicts. Otherwise, it didn’t seem to have major safety issues—and it was not highly addictive. “It doesn’t reward binge behavior,” Bowden says of BZP. “The next day you feel like you don’t want to have any more for a while.” Best of all, BZP was not on the list of controlled substances in New Zealand.

The more research he did, the more Bowden thought BZP could be a safe, or at least safer, legal substitute for meth. Clubbers wanted a drug that provided energy for all-night dancing. Rather than try to squelch that demand, why not offer a different substance that served the same function but was difficult to overdose on?

In 2000, Bowden began to have modest quantities of BZP made in India, in the sort of factory where the pharmaceutical industry often outsources production of medications. His plan was to test the market for the drug by giving it to friends who used meth on the dance floors of Auckland.

What Bowden didn’t predict was that he himself would end up turning to BZP in much the same way a heroin addict turns to methadone. In their telling, the couple kicked meth by using the new drug as a kind of DIY replacement therapy. “I addressed my addiction issues at a biological level,” Bowden says. And as he watched people use BZP around him in Auckland, he realized that others were doing the same. “It was working,” he says. “People were able to get their lives together, hold down a normal job, and end their involvement with organized crime. We thought it was pretty important.”

At least in his own mind, Bowden was on the verge of becoming a drug lord with a social mission.

It’s always hard to parse the motives of people who aim to “do well by doing good,” and even more so when powerful psychoactive substances are involved. But in any case, once he was satisfied with his test of the market, Bowden began to market BZP to the masses under the aegis of his company, Stargate International. He sold the drug in head shops and convenience stores, competing directly, he hoped, with the country’s meth dealers. It helped that there were no clear laws against selling BZP.

And sell it did: His customer base quickly climbed to half a million. Within a few years, a study would find that 20 percent of adult New Zealanders had tried “legal party pills”—as products made from BZP rapidly became known—and 44 percent of respondents who reported having used both legal party pills and illegal party drugs said they’d used BZP to replace the illegal drugs. Soon, the press in New Zealand was spending less time writing about the country’s meth epidemic, and more time sounding the alarm about an epidemic of drugs like BZP.

But the story was, in fact, much bigger than that.

What Bowden didn’t yet realize, in the early 2000s, was that he and New Zealand were on the forefront of a global explosion in recreational drug innovation—an Internet-driven market revolution no less profound than those now upending industries like media, fashion, and taxicabs.

Around the same time that Bowden was synthesizing his first BZP, other drug-geek “psychonauts” worldwide were discovering that they, too, could order “research chemicals” online from lab supply companies, with little scrutiny. Much of the actual manufacturing happened in India or China, where thousands of entrepreneurs were happy to synthesize chemicals on demand.

How do you define a “low risk” recreational drug? Accepting the level of risk associated with, say, cigarettes would legalize virtually anything short of absolute poison. After all, half of smokers die from their habit.

At first, only highly educated hobbyists were involved, ordering drugs, tweaking formulas, and trading notes on their effects in online forums. But soon, Western entrepreneurs got in on the game, using on-demand supply chains and online communication networks to peddle a cornucopia of substances gleaned from research papers and patent applications. The drugs were obscure and unfamiliar, but they were also legal—or at least unrecognized on the world’s schedules of banned substances—so they traveled fast.

New Zealand, an isolated island nation where popular traditional drugs are harder to come by, was one of the first countries to see the commercial spread of so-called legal highs (thanks in no small part to Matt Bowden). But when a worldwide ecstasy shortage in 2008 spiked the price and lowered the quality of traditional club drugs, the market for legal highs went global. The new drugs started to show up worldwide in online marketplaces, at head shops, even in gas stations—and, finally, on the radar of the world’s drug control agencies.

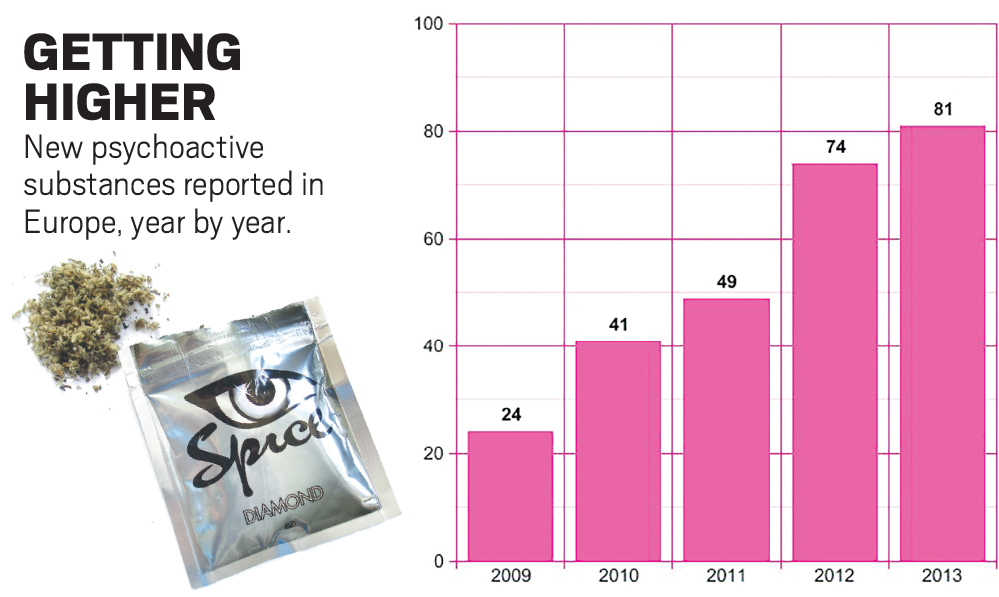

In 2005, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction established an early-warning system to track the appearance of new drugs on the continent. In its first years, the number of new psychoactive substances in Europe held fairly steady, hovering around 10 per annum. But in 2009 the figures began a steady ascent: from 24 new substances reported that year to 41 in 2010, 49 in 2011, 74 in 2012, and 81 in 2013.

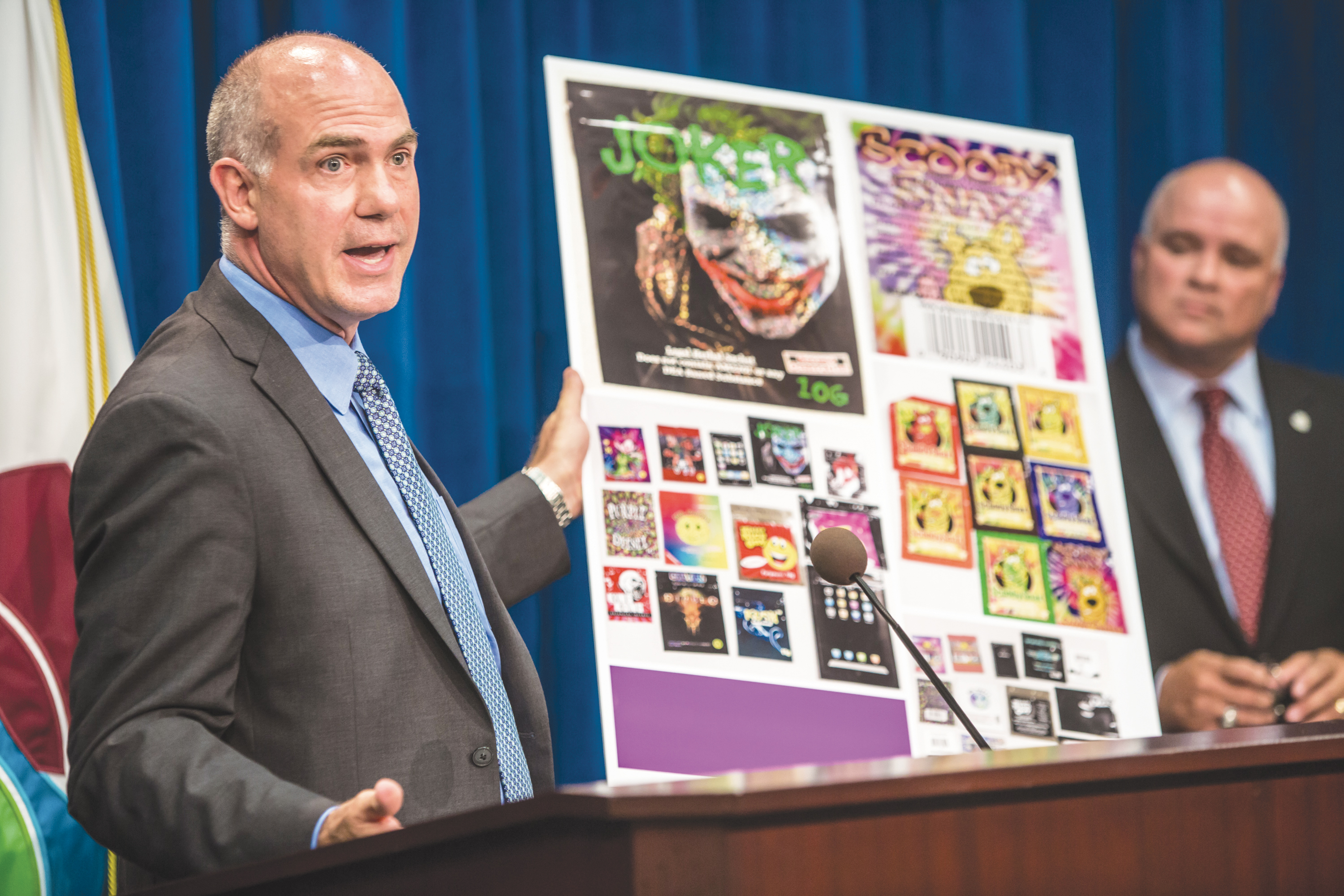

Worldwide, more than 350 new substances are now marketed as alternatives to marijuana, amphetamines, and other drugs, branded with names like bath salts, Spice, K2, and Blaze, according to the United Nation’s drug control agency. In the United States, by 2012, over 11 percent of high school seniors were reporting that they had tried at least one of these new psychoactive substances, usually a synthetic cannabinoid designed to substitute for pot. That made synthetic marijuana the second most popular class of drugs among American teens, after marijuana itself.

Drug control has always been a Sisyphean task. The use of mind-altering substances and techniques is regarded by anthropologists as a “human universal”—a cultural practice as basic to societies in every region and every period in history as trade, religion, and folklore. And after more than a trillion dollars spent, the American war on drugs has not put much of a dent in the trafficking and consumption of the substances our legal system has chosen to outlaw. Now, this new class of drugs makes controlling the supply of, say, heroin look easy by comparison. New psychoactive substances are coming out so quickly that it’s not possible to ban them fast enough to keep up, let alone police or scientifically understand them. When one substance is outlawed, another is born, just chemically distinct enough from the last one to evade its ban.

In 2013 and 2014 alone, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency banned 20 new psychoactive substances. All over the world, the pattern is the same. “Chemists need just three hours to change the formula, but all the necessary bureaucratic work to identify and then ban a particular drug takes five months,” said Sultan Khamzayev, an anti-drug member of Russia’s Public Chamber, as reported in the Guardian. “That means for the whole period, people can simply sell any old poison.”

Perhaps the most perverse thing about the rise of legal highs is that, in a scenario that is the direct opposite of what Matt Bowden was trying to engineer in New Zealand, these new, easy-to-acquire drugs are often more dangerous than the illegal drugs that they copy. Marijuana has been consumed for thousands of years, it has been studied in hundreds of clinical and epidemiological trials, and its relatively benign effects are well understood. Synthetic pot, on the other hand, is made with chemicals that may never have been tested on animals or humans. And yet hundreds of millions of doses are being sold over the counter to consumers trying to avoid the criminal activity of buying weed. Not surprisingly, some of these new substances are associated with psychosis, addiction, and death.

Not since the 19th century—when an earlier wave of globalization rapidly accelerated the spread of opium, cocaine, marijuana, and hazily defined “patent medicines”—has there been such a burgeoning and unregulated pharmacopeia. And by all indications, the future promises only more acceleration. Last year, a research lab at Stanford demonstrated that it’s possible to produce opioid drugs like morphine using a genetically modified form of baker’s yeast. Soon, even the production of traditional illegal drugs or illicit versions of pharmaceuticals could become a highly decentralized cottage industry, posing the same kind of regulatory challenge that the specter of 3-D printed firearms poses to the project of gun control.

In 2013, the U.N.’s World Drug Report summed up the global situation this way: “The international drug control system is floundering, for the first time, under the speed and creativity of the phenomenon known as new psychoactive substances.” Testifying before Congress that same year, the DEA’s Joseph Rannazzisi said that his agency could not keep up with “the clandestine chemists and traffickers who quickly and easily replace newly controlled substances with new, non-controlled substances.”

This state of desperation explains why the international community is watching with something like bated breath—or at least with more interest than suspicion—as one nation engages in an experiment that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago.

In 2013, New Zealand passed a law creating the world’s first set of regulations to allow the clinical testing and approval of new recreational drugs. Much as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration does for medicines, New Zealand’s system stands to create a government-regulated market for legal highs—an attempt to tame the industry not by stamping it out, but by guiding consumers to safe, reliable products, and giving suppliers an incentive to bring such products to market.

It’s worth pausing to consider what a profound departure this is. For most of human history, each culture has enjoyed its own favored repertoire of approved highs, with often striking variation between cultures. (For a time in the Ottoman empire, the consumption of coffee and tobacco was punishable by death, while opium and cannabis were legal.) Typically, the introduction of new psychoactive substances occurred only through contact with other cultures. These new drugs were often banned in moral panics that associated their use with foreigners or racial minorities—as opium, cocaine, and marijuana were here in America—and not because they were rationally or scientifically compared against the favored substances of the dominant group. Our current drug control regime—with its track record of racially imbalanced incarceration and monumental expense—is, in large part, a legacy of this process. New Zealand is the first country to try something different.

As a result, the eyes of the drug control establishment are fixed on a small island nation best known as the backdrop for the Hobbit movies. Which is even more surprising when you consider how the country came to its unprecedented position, and the person who spearheaded the campaign to get there: a flamboyant drug manufacturer, musician, and former meth addict named Matt Bowden.

Stargate International’s main laboratory, which has gone on to develop other new products since the early days of BZP, sits in a squat building tucked away in a light industrial area outside Auckland. The structure is nearly indistinguishable from nearby businesses that handle more mundane products like auto supplies and paint. The interior of Bowden’s lab is a sea of gleaming chrome countertops, with primary-colored lockers full of various caustic and flammable chemicals. Diamond-shaped signs warn of hazards like corrosive and “ecotoxic” substances.

Given the drug lab setting, the comparisons to Breaking Bad practically write themselves.

First, to give a sense of scale: Walter White’s fictional meth operation employed only one trained chemist, White himself. Bowden’s drug operation employs five. While White’s calling card was blue meth, Bowden marks his products with a symbol that looks like a cross between a heart and a lotus flower, which he and Kristi, now married, have tattooed on their fingers in place of wedding rings.

Over the course of his meth career, Walter White took on the look of a cerebral villain, with a trademark porkpie hat. Bowden, for his part, has come to resemble a kind of working man’s David Bowie, if Bowie was really into steampunk. In addition to Stargate, Matt and Kristi own a “retrofuturist” costume business that rents out corsets, Victorian leg-of-mutton-sleeved blouses, platform shoes, leather jackets, and the like. (The couple’s 10-year-old daughter, Shizandra, rolls her eyes at the notion of playing dress-up: To her mind, that’s what adults do.)

And while Walter White’s criminal nom de drug was Heisenberg, Bowden performs music—and occasionally advocates for drug reform—in the persona of his alter ego, an “interdimensional traveler” called Starboy. (In 2013, Starboy toured Ibiza, Macedonia, Austria, and Scotland; Kristi is one of his stage dancers.)

But the major practical difference between Bowden and TV’s most iconic drug lord is that Bowden does not have to evade the law. Government agents have been to Bowden’s lab—not to raid it, but to ensure that his equipment and safety standards are up to snuff.

Bowden himself certainly doesn’t hide from the public. One morning a few months ago, he was standing in an anteroom outside his lab, having his make-up done in preparation for an interview with Al Jazeera. At 43, he’s slender, with hazel eyes, a trim goatee covering a slight chin, and nearly shoulder-length tousled brown hair. He wore a deep brown, yellow-spotted shirt with an open collar and an olive patterned scarf knotted around his neck in place of a tie—an outré outfit for a businessman, but conservative by Bowden’s standards.

As he got his face powdered, Bowden chatted with one of his chemists about which Erlenmeyer flasks and centrifuges might look best on camera. For a man who has come to be known in his country as “the godfather of legal highs,” the past decade has been a crash course in public relations. One lesson learned: Bowden keeps his make-up artist on call. A past media appearance without it, he says, made him look sweaty and disreputable.

Bowden’s media exposure began back in the mid-2000s, when New Zealand’s newspapers and TV news shows first caught wind of the party pill phenomenon, as the rise of BZP came to be known in the press. The coverage was as leery as one might expect family newspapers to be toward a class of powerful drugs readily available in convenience stores. “Have New Zealand authorities been caught napping on the latest chemical craze?” asked one fairly typical article.

The U.S. has officially remained silent in response to New Zealand’s move to set up a regulated drug market, which is remarkable enough. Other international bodies have felt free to be open-minded, if not outright supportive.

But Bowden managed to show up in virtually every one of these articles, ready with a quote about how the proper way to market BZP was as “a safe alternative to drugs.” Even early on, he had his eye on the long game, arguing that new psychoactive substances ought to be regulated and controlled by the government itself.

By 2004, in the face of mounting public concern, Bowden and BZP were under investigation by the New Zealand Ministry of Health. Here, too, Bowden met the scrutiny head on. He went directly to the Health Ministry—often dressed in rocker regalia, sporting waist-length blond cornrow braids—and began meeting with parliamentary advisory groups like the Expert Advisory Committee on Drugs.

Stargate’s response to the country’s meth epidemic, Bowden argued, was consistent with New Zealand’s own national drug policy. Like many European countries, New Zealand had embraced the principle of harm reduction, which accepts that some drug use will always occur and aims to minimize the damage associated with it, rather than focusing solely on cutting off supply. In this case, Bowden argued, the best way to cut harm, and drive down demand for dangerous products, was to come up with safer drugs that could be clearly, credibly marketed as such.

New Zealand is a small country of 4.5 million people with a small government occasionally capable of surprising level-headedness. When the Ministry of Health responded to the uproar by ordering an expert committee to study BZP, one member of the team was Dr. Doug Sellman, a former director of New Zealand’s National Addiction Centre at the University of Otago in Dunedin. Sellman looks the part of the distinguished researcher, with short white hair, glasses, and an air of genial authority. Given that it was his job to investigate BZP, Sellman decided to try the drug himself.

“I went down to Cosmic Corner,” he says, referring to a head shop where he must have looked as out of place as a suit at a Phish show. “They gave me this little packet. I went home on a Friday night and took it and sat in front of the television, waiting.”

Nothing happened, he says. “But the extraordinary thing was that I was still sitting in front of the television at four o’clock in the morning and I just didn’t need to sleep.” The next day he had what he describes as the world’s worst hangover. “I went back to the [committee] and said, ‘You don’t have to worry, really, about this drug,’” he says, citing the lack of euphoria and the aftereffects.

In April 2004, Sellman’s committee released its report, concluding that BZP didn’t fit the definition of a dangerous drug and therefore shouldn’t be outlawed—but that it didn’t fit into other legal categories like food or medicines, either. The report suggested that the government consider creating “new categories of classification that can incorporate some levels of control and regulation.” Quietly, the legislature decided to establish such a category and began going about the long process of laying the groundwork.

In the meantime, the party pill market exploded. Bowden had long had some competitors who copied his success with BZP-based products. But now that the government had given its implicit blessing, the floodgates opened. In the absence of regulations, entrepreneurs would buy a kilogram or two of pure BZP from chemists in China or India, cut it, and distribute it in bags. Some sold BZP in extremely high doses. Users began taking the drug to extend alcohol binges.

By 2006, 40 percent of New Zealand men between the ages of 18 and 24 reported having used party pills at least once in the past year, and one in a hundred party pill users reported having visited an emergency room as a result of their drug use, often with symptoms like seizures, shaking, and confusion. The retail market was pulling in more than $15 million annually. By 2007, misuse of the drug had become a national political hot button, with politicians calling BZP a “gateway drug” and a cause of “severe psychosis.” In 2008, the pendulum swung against Bowden, and BZP was banned in New Zealand.

Rather than tamp down drug use, the prohibition of BZP set off an early version of a pattern that is now familiar globally: the legal highs arms race. Because there was a demonstrated demand for party pills among the public, and because a critical mass of entrepreneurs was already in the business, the ban was more a spur to innovation than a shutdown.

The number of new drugs proliferated rapidly, and the bans began to pile up. One substance would be outlawed, only to be replaced on the market by another drug, sometimes more harmful than the last. “I’ve banned 33 separate substances, 51 or 52 different products, and they keep being reformulated and reappearing,” New Zealand associate health minister Peter Dunne told a local paper, looking back at the worst period, in 2013. By then over 4,000 New Zealand stores were selling legal highs without age restrictions.

Once again, political pressure mounted for something to be done. But what, exactly? Banning a whole possible universe of drugs is, it turns out, a very different matter from banning an individual drug—which is precisely the problem that the rise of legal highs has forced on the world.

Countries cannot outlaw everything that gets you high: That would rule out alcohol, coffee, tobacco, and maybe sex and rock-and-roll. They also can’t easily outlaw drug analogs, preemptively banning anything that’s chemically similar to known drugs like pot, cocaine, and the like. America has tried, but such legislation is hard to enforce, because some molecular look-alikes act in differing and even opposite ways—and some drugs that appear quite dissimilar chemically can have virtually identical effects.

Moreover, a blanket ban on any chemical that can substitute for the likes of marijuana, heroin, or cocaine runs the risk of accidentally banning, say, the cure for Alzheimer’s. Once a drug becomes a controlled substance, research on it is restricted and often requires expensive licensing fees. Many companies abandon it.

The more you look at these problems, the less possible it seems to ban one’s way out of them. As New Zealand came to grips with its legal highs crisis, the solution that eventually rose to the fore was the one Bowden had been championing for years: Allow drugs to be sold, but only the safest ones.

Over the years, Bowden has become as much a professional lobbyist as a drug maker, though he has sold many products, ranging from an ecstasy substitute to synthetic cannabinoids. In late 2004, he founded a trade group called the Social Tonics Association of New Zealand—“social tonic” being his euphemism of choice to avoid the moral stigma attached to the word “drug.” And for a time in the mid-2000s—during which Bowden cut his long hair and took to wearing suits—he drew his primary income from the group, serving as a full-time official spokesman for the legal highs industry, arguing for regulation and reform.

He has been surprisingly effective. For all his manifest oddness, Bowden is disarmingly intelligent. (He was something of a prodigy as a youth, entering university at age 16 to study music, math, and computer science.) And over the years, he has gradually acquired a reputation as a smart, responsible businessman. Donald Hannah, a regulatory expert in New Zealand, regards most sellers of legal highs as “very clearly bordering on the dark side of society.” He sees Bowden, however, as one of the few manufacturers “who want to do it properly.”

Banning a whole possible universe of drugs is, it turns out, a very different matter from banning an individual drug. Countries cannot outlaw everything that gets you high: That would rule out alcohol, coffee, tobacco, and maybe sex and rock-and-roll.

“He knows this issue better than anyone,” says Ross Bell, the executive director of the New Zealand Drug Foundation, a drug policy think tank, regarding Bowden. Bell doesn’t always love how Bowden’s persona plays in the press (Bowden’s 40th birthday party, for instance, was a lavish media event that featured women on a trapeze, a laser show, and the debut of his heavily made-up “interdimensional traveler” alter ego). And Bell sometimes suspects that Bowden is being cynical when he dresses his self-interest in rhetoric about harm reduction. But none of that stopped Bell’s organization from adding its voice to the push for regulation.

As it became clear that the new legal highs market was dwarfing the old market for BZP, the coalition in favor of regulation grew. Bowden hired Chen Palmer—a law firm headed by a former prime minister—to serve as a lobbying arm. Together, they helped draft the language of what would become the Psychoactive Substances Act of 2013.

As public demands for action heated up, Bowden’s more politically mainstream allies made the case that regulation was the only way to keep the drugs out of the hands of kids and protect consumers. Proponents of the proposed law presented it not as a call for legalization, but as a kind of crackdown—a measure that would make the industry responsible for proving that its products were safe. “We are reversing the onus of proof. If they cannot prove that a product is safe, then it is not going anywhere near the marketplace,” said Dunne, the associate health minister, during debate over the law. “The new law means the game of ‘catch up’ with the legal highs industry will be over once and for all.”

In the summer of 2013, Parliament went to a vote, and the Psychoactive Substances Act passed by a margin of 119 to one. It’s not clear whether all the politicians who voted for the law fully realized that they were creating the world’s first regulatory system for recreational drugs, but that’s what they did.

The law mandated that legal psychoactive substances could only be purchased by an adult at a licensed outlet. To determine which substances ought to be legal, the law required manufacturers to conduct clinical trials, find “low risk” products, and sell only those that passed. And to preside over this new market, the law established a brand-new, FDA-like agency called the Psychoactive Substances Regulatory Authority—an office whose unenviable first task was to define and iron out the million gory details of what all of this might actually mean in practice.

In the past, whenever foreign countries have broken ranks with the U.S.-led consensus on drug control, the diplomatic response has been harsh. The U.S. has long demanded that other countries institute tough anti-drug laws as a condition of American aid, and has threatened to withdraw this support when countries have moved to liberalize. According to David Bewley-Taylor, a scholar of drug control at Swansea University, the U.S. used this kind of pressure to stop Jamaica from decriminalizing marijuana in 2001, and to keep Mexico from reducing drug penalties in 2004. Behind the scenes, the U.S. has even pressured allies like Canada and the U.K. to remove “harm reduction” language from drug policy documents.

But in the face of the global surge in new psychoactive substances, something different has happened in response to New Zealand’s new law. The U.S. has officially remained silent, which is remarkable enough. Meanwhile, other international bodies have felt free to be open-minded, if not outright supportive. The U.N.’s drug czar, Yury Fedotov—normally a conservative Russian with strong drug warrior credentials—has called the New Zealand law “creative.” Drug policy officials from Britain, the Organization of American States, and the European Union have cited it as a possible model to emulate. And when Dunne attended the U.N. Commission on Narcotic Drugs meeting in Vienna in March, he said, there was “genuine interest” from around the world. In October, the premier scholarly journal in addiction research, Addiction, devoted an entire issue to New Zealand’s experiment.

If the drug control establishment has been taking especially careful notes on New Zealand’s first steps, it is because the country is dealing with some particularly vexing, inescapable questions. For instance: How do you define a “low risk” recreational drug? The question is more mind-bending than it might appear at first glance. Accepting the level of risk associated with, say, cigarettes would legalize virtually anything short of absolute poison; after all, half of smokers die from their habit. If you set the level of risk associated with alcohol as your standard, numerous deaths and injuries would still be acceptable: Booze causes six percent of deaths worldwide.

However, if the bar is set at the risk level associated with marijuana, which cannot cause fatal overdose and is less addictive than alcohol or tobacco, then few new drugs of any kind would be legalized. (Nor, for that matter, would many other forms of dangerous fun. The odds of death from swimming? Approximately one in 57,000. Climbing Mount Everest? nearly 1.5 in 100. In contrast, Bowden says, the odds of dying from BZP are less than one in 10 million.)

Other unprecedented tasks loomed over New Zealand’s new regulators as well. They have had to determine how to regulate manufacturing, imports, and sales, and how to create clinical trials for drugs with benefits that aren’t medical. (How do you scientifically measure and weight qualities like transcendence and euphoria against risks to health?)

But their first and most pressing challenge was to figure out how to manage the early days of the newly regulated market—the all-important transition period. Needless to say, none of the nearly 300 products that comprised New Zealand’s burgeoning, unregulated legal highs market had gone through clinical trials; in fact, very little was known about them at all. However, to ban all of those products right out of the gate would have sent consumers en masse into the arms of the black market. And so, in a calculated risk, the law allowed drugs that had already been sold, problem free, for at least three months to stay legal.

To define “problem free,” the Psychoactive Substances Regulatory Authority set up an online tracking system that allowed doctors and hospitals to report adverse events connected to any given product. Using data from these reports, the agency started informally rating every product on the market using a modified version of a numerical scale devised by the Poisons Information Center in Freiburg, Germany. Minor risks to any bodily system rated a one; moderate risks a two; and severe, permanent, and life-threatening risks a three. Because the Freiburg scale was designed to measure acute poisoning, not addiction risks, the New Zealand regulators added measures for withdrawal. And minor effects were weighted differently depending on how frequently they occurred. Any substance that scored two or more on the scale would be banned.

Of the nearly 300 products on the market, a mere 41 survived this first test. These were granted interim approval. Legal sales began on July 18, 2013.

The interim regulatory regime hit rough water almost immediately. The trouble stemmed in part from an unforeseen problem: On the eve of the newly regulated market’s debut, the number of stores selling legal highs in New Zealand fell by 95 percent. (While it’s not entirely clear why this happened, it appears that some store owners were reluctant to go through the hassle of acquiring the requisite new licenses; conflicts between local and national authorities over the approval of specific sales outlets may have also helped winnow out the numbers.)

On its face, the sharp drop-off in retail outlets might have seemed like a win for the forces of regulation. Police, for one, said the market was much easier to keep tabs on. But the optics of the situation were terrible. Users concentrated near the few stores that remained, and so too did the TV cameras. Suddenly the legal highs business was more visible than ever. Video images of young, unhealthy people lining up outside legal highs shops “created the public impression of it being this huge problem,” Dunne says.

As it happened, 2014 was a national election year in New Zealand, which was another bad break for the Psychoactive Substances Act. Journalists and politicians called the policy a disaster. Incumbent politicians claimed that they hadn’t been aware of what they were voting for: Not expecting any substances to pass legal muster, they had thought that regulation would be de facto prohibition.

In May 2014, less than a year into the experiment, Parliament passed a revision to the Psychoactive Substances Act. It banned all of the substances that were then on sale. It also prohibited the use of animal testing in New Zealand in trials for new ones.

Many in the New Zealand media called the amendment the practical end of the Psychoactive Substances Act. But Dunne insists otherwise. “It’s not that we suddenly had a U-turn,” he says. The only real change, he says, is that the original batch of untested products that crept in under the wire of interim approvals are no longer legal.

Moreover, when it comes to animal testing, the new law may have a loophole. Nothing prevents a manufacturer from doing preclinical testing outside New Zealand, where it remains completely legal to study drugs in animals, and then moving to human trials with safe substances, as long as the animal results aren’t cited in the approval application. “I think that’s possible,” Dunne says. Hannah, who served as the first head of the Psychoactive Substances Regulatory Authority, confirms that a manufacturer who is relying on human tests that show a low risk of harm “should be able to make a valid application.”

New psychoactive substances are coming out so quickly that it’s not possible to ban them fast enough, let alone police them or scientifically understand them. When one substance is outlawed, another is born, just chemically distinct enough from the last one to evade its ban.

“The so-called New Zealand experiment remains,” Dunne says.

Bowden, too, is not behaving as if this is a defeat. When I visited him two weeks after the law changed, he was awaiting delivery of new high-tech lab equipment and remained positive about the future, having previously weathered the BZP ban. “I operate with a high degree of transparency with the authorities,” he says, adding that he will “absolutely” continue to try to get his products approved, though he would not publicly reveal his strategy. In the meantime, the press in New Zealand has already begun reporting on a spike in demand for black market products since the last legal highs were taken off the shelves.

It’s still far too soon to tell how the New Zealand experiment will turn out. It would be even more premature to predict what kind of influence New Zealand’s new law will have on the rest of the world. But it’s safe to say that Bowden’s crusade has come at a pivotal moment in the international realm of drug control.

Even in the United States, the consensus around prohibition is dissolving fast. Last November, two new states—Alaska and Oregon—joined Colorado and Washington in legalizing marijuana, and California passed a measure to lower sentences linked to drug use. A majority of American voters now favor legalizing pot.

Even the U.S. drug czar has said that he wants to end the drug war. The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy declared, as of 2009, that it would no longer use such rhetoric. “Regardless of how you try to explain to people it’s a ‘war on drugs’ or a ‘war on a product,’ people see a war as a war on them,” Obama’s first drug czar, Gil Kerlikowske, told the Wall Street Journal that year. Congress raced to pass the harshest possible drug laws in the 1980s; now, both Republicans and Democrats say they want to roll them back.

The United States has also started to embrace a principle that was until recently antithetical to its approach to drugs: harm reduction. Obama’s current drug czar, Michael Botticelli, spoke at the 2014 Harm Reduction Conference, an event that was viewed in drug policy circles as something akin to the pope addressing a conference on birth control. In official meetings at the United Nations, U.S. representatives no longer fight to remove language about harm reduction from official documents.

Indeed, in advance of a special U.N. session on revising drug laws in 2016, the U.S. has indicated that it would support “flexible” interpretations of international drug conventions and would even tolerate national policies that “legalize entire categories of drugs.”

None of this is to say that an American Matt Bowden is around the corner. But with the U.S. busy reckoning with its own drug policy changes, the rest of the world has room to experiment. The World Health Organization is calling for decriminalization of all personal drug use and possession—of cocaine, heroin, and the rest, not just marijuana. They’re joined by the Global Commission on Drug Policy, which includes the former presidents of Mexico, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Poland, Portugal, and Switzerland. Uruguay has fully legalized cannabis, and Jamaica is back to planning for decriminalization.

In the meantime, new psychoactive substances continue to be invented, and continue to do harm—building pressure on governments to come up with a response that actually works. CNN reported recently on the deaths of two American teenagers who had taken a new synthetic substitute for LSD, one far more deadly than the original, in 2012. And according to a 2014 U.S. government report, the number of American emergency room visits linked to synthetic cannabis-like drugs more than doubled between 2010 and 2011, from just over 11,000 to almost 29,000.

If nothing else, the next country that tries to create a regulated market for drugs will learn from New Zealand’s mistakes. For the first time, a nation has taken on the challenge of figuring out how to approve, test, and license substances that will safely get its citizens high. That’s not necessarily a pleasant thought for many people. But neither is drowning in a relentless flood of new and potentially dangerous substances.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psmag.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state.

For more from Pacific Standard on the science of society, and to support our work, sign up for our email newsletter and subscribe to our bimonthly magazine, where this piece originally appeared. Digital editions are available in the App Store (iPad) and on Zinio (Android, iPad, PC/MAC, iPhone, and Win8), Amazon, and Google Play (Android).

Lead photo: Matt Bowden dressed as his “interdimensional traveler” alter ego. (Photo: Dana Lee)