The health risks of radiation exposure are notoriously difficult to measure, but the link between radioactive iodine and thyroid cancer is among the strongest for any radiation-induced disease. The thyroid gland uses iodine to make hormones that are important to development and metabolism. From the Chernobyl nuclear accident in the Ukraine and the U.S. atomic bombings of Japan in World War II, there is good evidence that the ingestion or inhalation of iodine-131 causes genetic damage that in turn can lead to thyroid cancer.

In addition to iodine-131, nuclear fission reactions produce other radioactive iodine isotopes, including I-129. There is a lack of clarity as to iodine-129’s specific health risks. Iodine-131 may be more immediately dangerous; iodine-129 remains problematic for far longer. At any rate, federal policy requires that I-129 be isolated during any future nuclear fuel reprocessing and stored in a geological repository for high-level waste.

Most nuclear waste is a mix of many radioactive elements, the nastiest of which include plutonium, cesium, strontium and iodine. Commercial nuclear power plant waste (that is, spent fuel) can be immobilized and stored in the industry-standard glass logs via a process known as vitrification. But if nuclear waste is reprocessed — that is, sent through a second chemical ordeal to extract the remaining fuel it contains — the concentrated leftovers are another matter entirely. The U.S. has eschewed spent-fuel reprocessing since the 1970s because it separates plutonium from the radioactive soup, making it more accessible to terrorists wanting to make nuclear weapons.

But large-scale reprocessing and the need to dispose of iodine-129 would become an issue here if nuclear power revives as a significant U.S. energy option in a world of global warming. Even if commercial reprocessing never happens in the U.S., there is now no remediation technology available for the significant quantities of iodine-129 that have leaked into groundwater at nuclear weapons production locations, including the Hanford Site in Washington state. Meanwhile, France and England — which produce large proportions of their electricity via nuclear power — are reprocessing spent fuel and disposing of vast quantities of iodine-129 simply by dumping it in the ocean.

Tina Nenoff is part of a scientific team at the Sandia National Laboratory in Albuquerque, N.M., seeking a “waste form” in which iodine-129 can be immobilized. In its elemental state, I-129 is one of the most problematic of isotopes; it will change directly from solid to gas without going through a liquid phase. Because it likes to be a gas and is easily soluble in water, it is highly mobile in the environment. It also has a fairly low melting point, which rules out the borosilicate glass used to vitrify other high-level waste; temperatures high enough to melt glass will evaporate iodine right out of the mixture.

So how do you capture something that evasive and potentially dangerous and imprison it for at least its half-life — some 16 million years? The short answer is that nobody knows for sure, but Nenoff and her colleagues are leading the effort to find out.

Science runs in Nenoff’s family. Her father is a physician, her mother a science teacher, an uncle a chemist. The family always took a lively interest in the arts as well as the sciences. Growing up in Bergen County, N.J., Nenoff often visited New York City museums and performing arts events. She thought she’d follow in her father’s footsteps, but an inspiring high school teacher got her interested in chemistry for its own sake. In college, she still considered it just a prologue to medical school, but when a close friend fell seriously ill she realized, she says, “It wasn’t in me to be a doctor.”

At the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Nenoff worked under the late chemistry Nobelist Alan MacDiarmid, learning how to make organic polymers that would conduct electricity. At the same time, she was filled with awe watching grad students read ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. Here was just the kind of puzzle she liked — the kind that required both imagination and a consuming focus. She accommodated the pull of archeology by minoring in it, analyzing the art on ancient Greek pottery. She also took extensive courses in French language and literature. After earning a doctorate in chemistry at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and a brief stint in private industry, Nenoff arrived at Sandia in 1993.

Nenoff and her colleagues at the national lab are scouring the vast knowledge base of modern chemistry, seeking a permanent waste form for iodine-129, or at least a stopgap form that could tide the nuclear world over until the best is found. Each potential waste form has to be rigorously examined in the lab, undergoing structural analysis at the molecular, atomic and subatomic levels, using X-ray crystallography and scanning electron microscopy as well as tests to determine how well the material stands up to heat and pressure. The properties of likely-looking materials are also modeled and simulated on computers to generate predictions as to their interaction with iodine-129. The most promising candidates are run through their paces in a somewhat larger-scale industrial prototype to see what happens.

Possible waste forms for iodine-129 include both natural and synthetic materials. Given the range of possible solutions and the exquisite degree of “tuning” necessary for each radionuclide, a multidisciplinary team is essential. Nenoff can draw on the talents of a radiochemist, a ceramics specialist, a chemical engineer and various computer modelers and simulators. Her chief partner for the basic chemistry work is the affable, white-haired geochemist Jim Krumhansl.

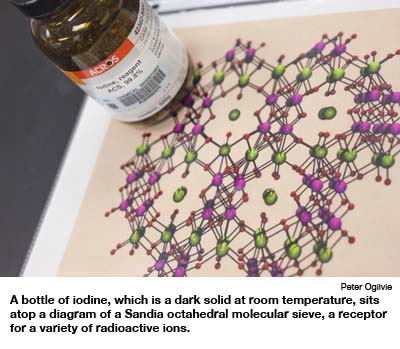

In his lab, Krumhansl keeps a sample of gaseous iodine in a bottle to show visitors its lovely magenta hue, delivering his chemistry lore with a patter of mild wisecracks. He displays a peanut-butter-cup-sized container full of an off-white rubbery goo enclosing some non-radioactive iodine; the material is a common industrial polymer, much like the silicone compounds used to seal plumbing. The Sandia team has found it quite good at grabbing iodine, but not so good at retaining it. They do think it could be useful as a temporary stabilizer for iodine-129 before it’s put into long-term isolation. Federal policy and planning in regard to nuclear waste reprocessing and storage are in flux right now; the scientists don’t know whether they need to come up with one long-term waste form, a shorter-term solution or both.

“This illustrates the problem you don’t want to have,” Krumhansl says. “I can’t tell you what in 16 million years this manmade organic material is going to do.”

Nenoff is a materials chemist, but she doesn’t look like one. Slender, with curly golden-brown hair and wearing a cashmere twin-set set off by a pearl choker, she could be relaxing at a social function on Martha’s Vineyard instead of moving purposefully through the nondescript halls and instrument-jammed labs in one of Sandia’s many buildings on a typical workday, handing out plastic safety goggles and showing off the work of her research team.

The Sandia National Lab was the Manhattan Project‘s nuclear weapons factory during World War II and today is responsible for keeping the United State’s nuclear warheads fresh and ready to go. The campus sprawls across the flat, drought-stricken outskirts of Albuquerque next to Kirtland Air Force Base with a full view of the 11,000-foot Sandia Mountains to the east. It is neither literally green nor has it historically been “green” in the environmental sense. But as the world’s ecological vulnerability becomes more obvious, funding priorities and research agendas are changing, even this deep in the heart of the nuclear establishment.

U.S. commercial reactors had generated almost 60,000 metric tons of nuclear waste by January 2008, according to the Nuclear Energy Institute. The waste is sitting in underground tanks, in pools of blue water or in dry casks at nuclear power plants around the country awaiting transfer to the long-promised, long-term deep geological repository at Yucca Mountain, Nev. Currently the Yucca Mountain project is in limbo, and no other site has been selected.

Nuclear power interests and some environmentalists insist they can help save the world from global warming through a renaissance of nuclear energy, using a new generation of safer reactor designs and resurrecting spent-fuel reprocessing in the U.S. But there are snags. The half-lives of many radioactive elements are so long that it’s unclear if they can be separated from the biosphere long enough for the radiation to decay to safe levels. Although reprocessing reduces the volume of high-level waste, it increases the concentrations of unwanted isotopes in what’s left and multiplies by twentyfold the total volume of low-level and plutonium-contaminated waste that must be stored, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thus many fear a nuclear renaissance might create more problems than it would solve.

At the least, it would probably mean a lot more iodine-129 to store.

So far, the most promising work of Nenoff and her colleagues focuses on zeolites, a class of metal oxide minerals with dense, clay-like textures riddled with very small pores. (Kitty litter is a type of zeolite.) Doping the pores of the zeolite with silver (known as a “getter” in the business) lures iodine-129 into the material, where it is happy to form silver iodide, the same compound used in photography and cloud seeding. Since silver iodide is a solid, the risk of iodine migration is much reduced.

The pore size of the zeolite has been engineered exactly for the silver iodide molecule, which is then trapped for, well, maybe not 16 million years, but probably at least the 10,000 years required for a deep geologic repository. And because the zeolite can be fired like a ceramic, it may be capable of serving as its own container. Ceramics harden and compress at lower temperatures than glass melts, so the risk of vaporizing the iodine during processing is lower than with vitrification. Nenoff hopes to show that copper — much less expensive and environmentally problematic than silver — is also a good “getter.”

Government statements about the health risks of iodine-129 are inconsistent. The Centers for Disease Control has a Priority List of Hazardous Substances that tucks iodine-129 between the roach-motel insecticide chlordecone and plutonium-240 — both pretty nasty customers. Yet an Argonne National Laboratory fact sheet downplays the danger, saying I-129’s long half-life, sparse emissions and low energy “limit the hazards.” Neither the Environmental Protection Agency nor the Department of Energy responded to repeated requests for clarification and comment for this article.

If the iodine-129 problem is ill-defined, that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily small. The world’s two largest emitters of iodine-129 are the spent-fuel reprocessing facilities at Sellafield on England’s west coast and Cap de La Hague on France’s west coast. As of 2004, the two plants had discharged about four tons of iodine-129 into the ocean and were holding another 60 tons in spent fuel waiting to be reprocessed.

Since the ocean already holds most of the planet’s natural supply of iodine, the European nuclear industry has had no qualms about putting the manmade iodine-129 there, reasoning that the radioactive isotope would be largely diluted by the stable form. Just the same, ocean disposal of iodine-129 appears to have resulted in massive increases of radionuclide concentrations. Currents carry the British and French iodine-129 northward, and a 2003 Danish study found concentrations in the Kattegat strait between Denmark and Sweden increased sixfold between 1992 and 2000. Concentrations of iodine-129 in some Arctic waters are 4,000 times their pre-nuclear era levels.

The U.S. government could always change its mind about the dangers of iodine-129. Two of the most likely bidders for reprocessing spent fuel in the U.S. are the existing French and British reprocessors who now put iodine-129 in the ocean.

Still, the U.S. government’s plans to sequester iodine-129 as high-level waste — and its continued support for research like Nenoff’s — suggests significant official unease. And when it comes to nuclear waste, there can be many a slip twixt lab and repository. It appears that Yucca Mountain may remain simply a long ridge of compressed volcanic material, and if it does, the search for a new U.S. nuclear repository will begin. That search will probably necessitate even more research into storage materials, because the chemistry of the waste forms must be tuned to the geochemistry of a specific repository site.

As the country’s approach to nuclear power in the era of climate change is debated and decided, Nenoff maintains the pace and approach her friends have admired since her college days, applying both intense focus and an ability to discern fruitful patterns in the hieroglyphs not of ancient cultures, but of chemistry. For her, finding a “good enough” waste form to contain iodine-129 isn’t an option.

“If the waste form doesn’t work perfectly well,” she says, “then we not only have iodine gas waste, we have iodine gas waste plus this gunk we’ve made that’s now contaminated.

“So you just don’t ever want to create more waste. That’s a big no-no.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.