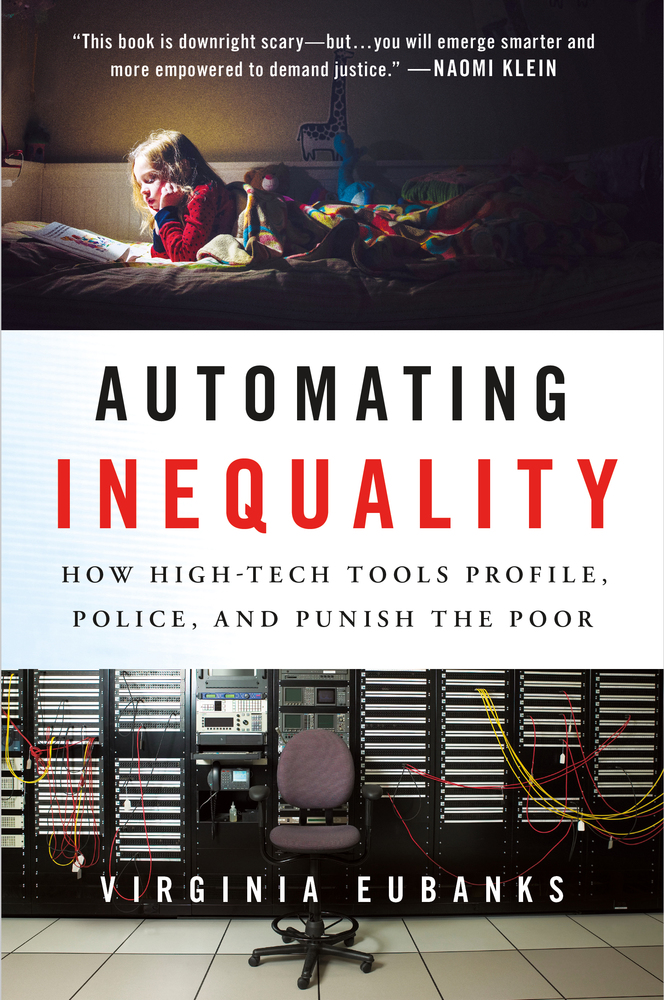

(Photo: St. Martin’s Press)

Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor

Virginia Eubanks

St. Martin’s Press

Imagine walking down a street in contemporary America and suddenly finding yourself in front of a building that advertised itself as a poorhouse. You would be shocked. The word conjures up a paternalistic, punitive approach to poverty that we like to think we’ve moved past: the dank, dusty stuff of Charles Dickens novels, not 21st-century American life.

In her new book, Automating Inequality, the scholar and activist Virginia Eubanks insists that the poorhouse is very much still with us, and very much still working to isolate, surveil, judge, and punish the poor. But the poorhouse of 2018 isn’t an actual building; instead, it’s an “invisible spider web” of computer networks used by the American state to mediate our relationship to poverty. Eubanks calls this web the “digital poorhouse,” and she wants us to dismantle it.

Some books are valuable because they provide us with a definitive, magisterial overview of an important topic. This is not one of those books. Instead, we get the sense of Eubanks plunging into new territory, flashlight in hand, reporting back with her first impressions, suspicions, and fears. Her picture of the digital poorhouse is extrapolated almost entirely from three detailed case studies, all from the last decade, and all representative of broader trends: the switch to a computerized system for determining public-benefit eligibility in several Indiana counties; the rollout of a computer formula designed to optimize the process of getting the homeless people of Los Angeles into housing; and the implementation, in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, of an algorithm designed to predict which children are at the greatest risk of neglect or abuse.

This approach has its virtues. Most important, it gives plenty of space to the voices and experiences of poor people stuck in the frustrating bureaucratic webs of contemporary poverty. Readers will get some sense of the lives of thousands of Indiana residents who one day received confusing, automated notices that they were no longer eligible for Medicaid, food stamps, or cash assistance, with no clear explanation as to why beyond the sinister-sounding “failure to cooperate.” They will hear from homeless Angelenos who submit to intrusive surveys about their criminal histories and mental lives, only to end up still sleeping outside, struggling to keep their lives together. These individual stories are the book’s human heartbeat.

But relying so closely on just three case studies, however detailed, also has clear limitations—especially when it’s not always clear what exact role Eubanks is trying to claim for the “high-tech tools” of her subtitle. I suspect many readers will come to Automating Inequality quite ready to buy into a frightening notion of the hyper-connected digital poorhouse, its methods of discrimination fine-tuned and supercharged by Big Data. We live in a golden era for suspicion of the networks, data collectors, and algorithms that are increasingly integrated into our daily lives. This suspicion is certainly warranted, especially since for so long our shared narratives about technology were uncritically triumphalist. But at times, Eubanks seems in a rush to place digital technology at the center of the plot in the service of her overarching thesis.

Take Indiana, for example. In 2006, the state’s then-governor, Republican Mitch Daniels, had been an opponent of public assistance for decades before he outsourced welfare eligibility to a for-profit computing company. The contract all but required this company to reduce the number of approved applications. Daniels wanted fewer people on the government’s benefit rolls, and he found a way to get that. Even though an eventual public outcry forced a switch back to a state-administered system with more human contact, benefit enrollment in Indiana remains at a historic low. It’s a sad saga, filled with needless suffering. But is it really a story, as Eubanks’ subtitle would have it, of a change wrought by “high-tech” tools? The fancy-sounding computer system was, in practice, barely more sophisticated than a ticket dispenser stuffed randomly with NO slips—window dressing for a transition to callous austerity.

The story of the L.A. housing-match program has a similar dynamic. Eubanks is able to poke all kinds of holes in the methodology of the survey behind the program. Ultimately, though, she makes quite clear that the biggest problem with the software lies beyond the software: There simply isn’t enough affordable housing to accommodate all the Angelenos who need it. “Homelessness isn’t a systems engineering problem,” a lawyer for the homeless tells Eubanks. “It’s a carpentry problem.” So, again, centering the software seems like an odd choice. Eubanks raises the very serious concern that individuals’ survey responses, which can include their accounts of illegal activity, might be all too easily accessed and exploited by police. But, in a book driven by real-world examples, she doesn’t give a single one here. The problem, then, remains plausible but speculative.

(Photo: Jerome Sessini/Magnum Photos)

It’s only in Eubanks’ final example—the Allegheny County child-safety algorithm—that the digital poorhouse comes into focus as a distinct modern entity, not just a speculative future outcome, or a new flavor for old brutality. This is because the Allegheny algorithm is fed not only by referrals from the public and by caseworker notes, but also by records of individuals’ every other interaction with state aid. Coming to the state for help with anything from food stamps to psychological counseling automatically bumps up your numerical score, which inevitably increases your chances of being flagged and investigated as an abusive or neglectful parent. Of course, when middle-class and wealthy people pay private providers for help with their struggles, the database makes no record of it. Poverty puts you on the system’s radar, and poverty makes the system—now armed with a powerful central database—more likely to further impose its scrutiny and judgments on your private life. It might even remove your child from your custody. These judgments pass down through generations: Childhood interactions with social services also bump your score up.

If Eubanks’ first two cases are infuriating, this last one is terrifying. In Allegheny County there are still decent safeguards in place against the possibility of algorithmic error. But Eubanks is worried about what might happen to those safeguards in a different political climate, or against the backdrop of extreme budget cuts. The answers are already playing out in cities and towns across America. It’s likely digitized approaches to poverty are ensnaring more people than ever before, thanks not only to the decline of the middle class, but also to the growth of networked data in American public life. Automating Inequality is a decidedly tentative, preliminary, and at times conceptually cloudy book. But it is also an important book, with the ring of truth. We need more to follow in its footsteps, and beyond—books showing every strand on this spider web, and how they all connect.

A version of this story originally appeared in the February 2018 issue of Pacific Standard. Subscribe now and get eight issues/year or purchase a single copy of the magazine.