The day’s heat rose off the pavement, men squatted on the roadside chewing betel leaf, women in their fading thanaka face paint urged their impish children along: a standard night in Yangon, the largest city in Myanmar. But as I crossed the threshold of the underpass of the Nar Nat Taw Bridge, traditional decorum gave way to bedlam.

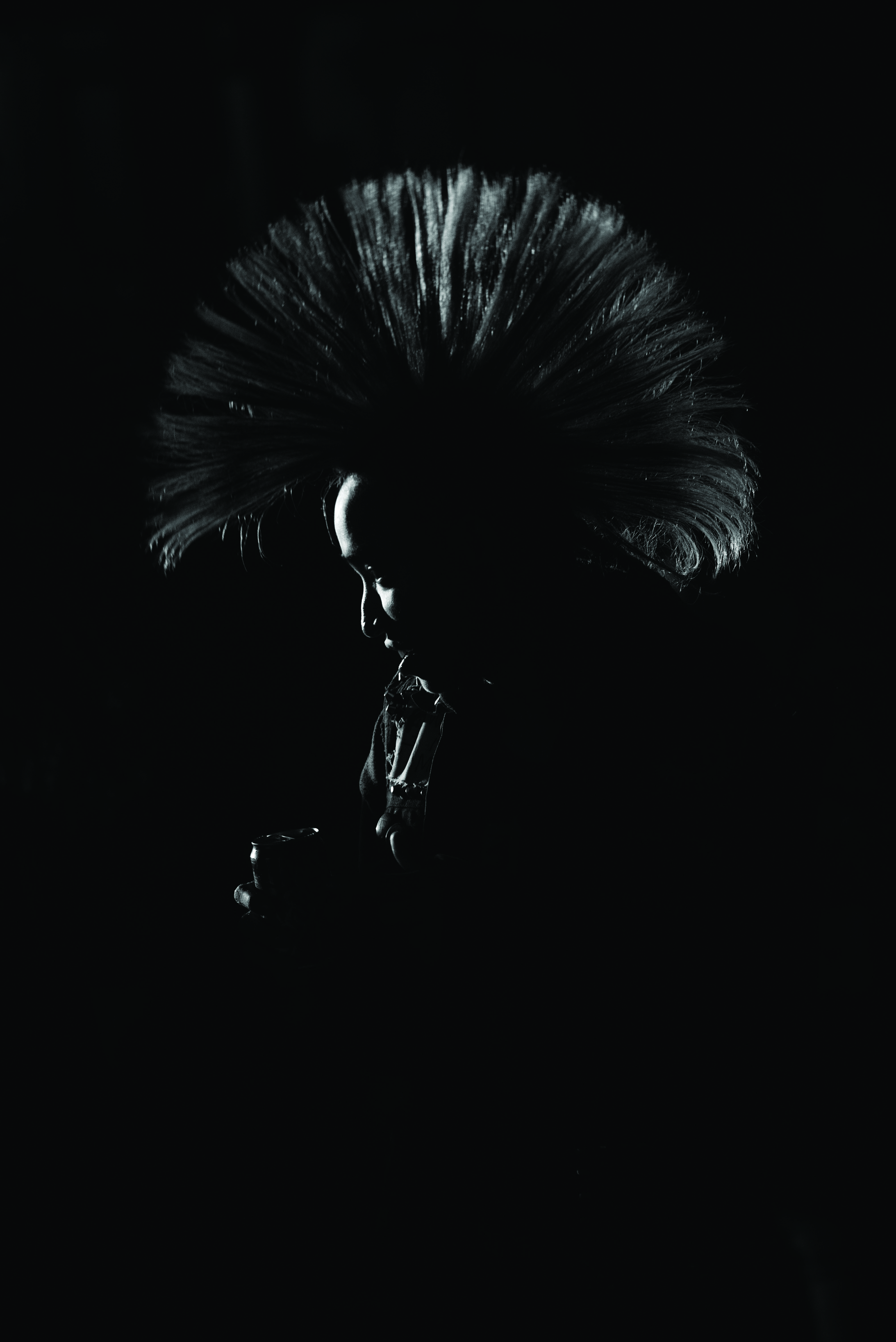

(Photo: Jerome Sessini/Magnum Photos)

I walked past a row of teenagers in studded leather jackets and combat boots leaning against the graffiti-covered concrete wall, smoking cigarettes with an air of impatience. In front of me, a mohawked punk with a Black Flag patch on his vest lay on the dusty ground yelling “FUCK YOU” at nothing in particular, one hand clutching a spiked liter bottle of Coca-Cola, the other brandishing a middle finger toward the sky.

Tonight, in the last hours of 2016, a couple hundred Burmese youth and a handful of curious foreigners had collected in this grimy spot on the outskirts of Yangon to hear some of the city’s biggest underground punk bands in an open-air show billed as a “Fucking New Year Punk Gig.” In the midst of an unfamiliar culture, I’d found something temperamentally familiar: a group of people yearning for a radical rearrangement of their society, choosing music as their medium of opposition. The guy next to me, an older man from Chicago who said he was an erstwhile roadie for Metallica, was feeling it too and leaned in to talk about the raw intensity of the show—before noticing I was holding a camera and telling me to go fuck myself.

The noise and vulgarity was a stark departure from the quiet demeanor I’d witnessed elsewhere as I traveled through the Buddhist nation. Teens in tattered clothes held together with pins and patches danced and crashed into one another in a swirl of glorious sedition. The scene felt like an echo of all the stories I’d heard about the lost punk subculture of ’70s and ’80s New York: the rough, amateurish musicality, the threadbare fashion, the intoxication, the rejection of conventional propriety. And, of course, the hair.

The band Never Reverse was in the middle of a song called “Burning Society” when their amps and lights were suddenly shut off. We stood in darkness and silence. My ears were ringing and I was still waiting for my eyes to adjust when the kid behind me put his hand on my shoulder. “Cop nearby,” he murmured, seeing the confusion on my face. Someone had spotted a patrol car up the road and, not wanting the revelers to be noticed or harassed, unplugged the concert, leaving us hidden in the black of the underpass.

The cooperative quiet was a stunning juxtaposition to the recent chaos. But disappearing into the night is a routine operation for this crowd. In Myanmar, a country long held hostage by one of the most repressive military regimes in the world, the threat of government crackdown is especially ominous.

“It’s really annoying,” a guitarist named Eaiddhi says of the government’s restrictions on free expression. People have been arrested simply for donning punk attire, he tells me.

Eaiddhi had one of his songs banned and another’s lyrics changed by the country’s Press Scrutiny and Registration Division of the Ministry of Information, and says that censorship was one of his biggest hurdles when he started making music. “It took at least three or four months to get permission from the censorship department—unless you bribe them,” he says. “Sometimes they ask you to change the lyrics and sometimes they just ban the whole song.”

Myanmar’s quasi-democratic government, elected in 2012, jettisoned official censorship and disbanded the Press Scrutiny and Registration Division. It now prefers the model of self-censorship, using the infamous threat of section 66(d) of the telecommunications law, passed in 2013, to frighten critics into silence. The law, protested by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, is an ostensible protection against defamation and threats but is more commonly used to imprison dissenters.

Borrowing another control scheme from the playbook of socialist authoritarianism, Myanmar’s military junta tried to consolidate power by keeping the country strictly isolated for decades. But in Myanmar, as in the former Soviet Bloc, punk culture found a way to sneak in and take root among the disenchanted.

“In the past, when YouTube was still banned from the country, a sailor friend of mine bought a Punx Unite album from overseas and let me listen to it,” recalls Maung Nyan, the lead guitarist in Never Reverse. “The first song I heard was ‘Rebel’ by The Casualties.”

The Western influence among this crowd is unmistakable—in their music, fashion, and attitude. But perhaps the most salient similarity in the evolution of punk in New York and Yangon is that both cultures emerged from failed revolutions.

“I was born and brought up in the junta era in Burma [Myanmar],” Nyan says. “I became a punk musician because of the 2007 Saffron Revolution, [a revolution] initiated by monks and the people.”

During the Saffron Revolution, hundreds of thousands took to the streets, including mobs of Buddhist monks, demanding democracy and change. The military responded with a brutal crackdown. Hundreds were killed, thousands were arrested, and more were injured in unprovoked government attacks.

“I tried to find ways to rebel against the junta system. It became too dangerous to demonstrate in the streets,” Nyan says. “Finally, I found a way to demonstrate against the government using music.”

These artists’ disgust with their government is paired with an unforgiving critique of the toxic aspects of the country’s culture: homophobia, misogyny, racism, and a Buddhist nationalist movement that has encouraged ethnic cleansing. But they fall far short of a complete rejection of Myanmar society and culture, and seem to sidestep the nihilism that infects many contrarian music scenes. “It is not possible to go beyond society,” Nyan says. “People may try to say ‘fuck off’ to society, but they end up getting support from it. I am proud to be a punk musician in this country.”

Myanmar punks display a solidarity with the people of their city and country that might surprise early American punks, who lived through the failed utopianism of 1968. Here, there are no Richard Nixon voters, no suburbs of bloodstained wealth, no middle class clinging to post-war material comfort. Young to old, dissatisfaction with the status quo is ubiquitous. If American punk was adversarial and dismissive toward mainstream society, Myanmar punk has found a certain level of mutual understanding and cohesion with it.

About two hours into the New Year’s show I was completely lost in it, pretending I was 17 and basking in a glorious sense of adolescent completion. It was only when I left the middle of the floor to collect myself that I noticed a large crowd had amassed outside the underpass.

Just out of reach of the makeshift stage lights, a semicircle of middle-aged men in traditional Burmese sarongs, mothers carrying babies, children, and families stood together in the dark to watch the spectacle before them. Most had warm smiles on their faces, and when I waved they politely waved back. They didn’t seem shocked by what they saw, nor disgusted or offended. They seemed, most of all, curious.

There I stood, between the mob of punks and an arc of common families, without ever sensing an ounce of animosity in between. Perhaps I was simply seeing a calm moment in an otherwise antagonistic relationship. Or perhaps strange new things don’t frighten those who thirst for change.

A version of this story originally appeared in the February 2018 issue of Pacific Standard. Subscribe now and get eight issues/year or purchase a single copy of the magazine.