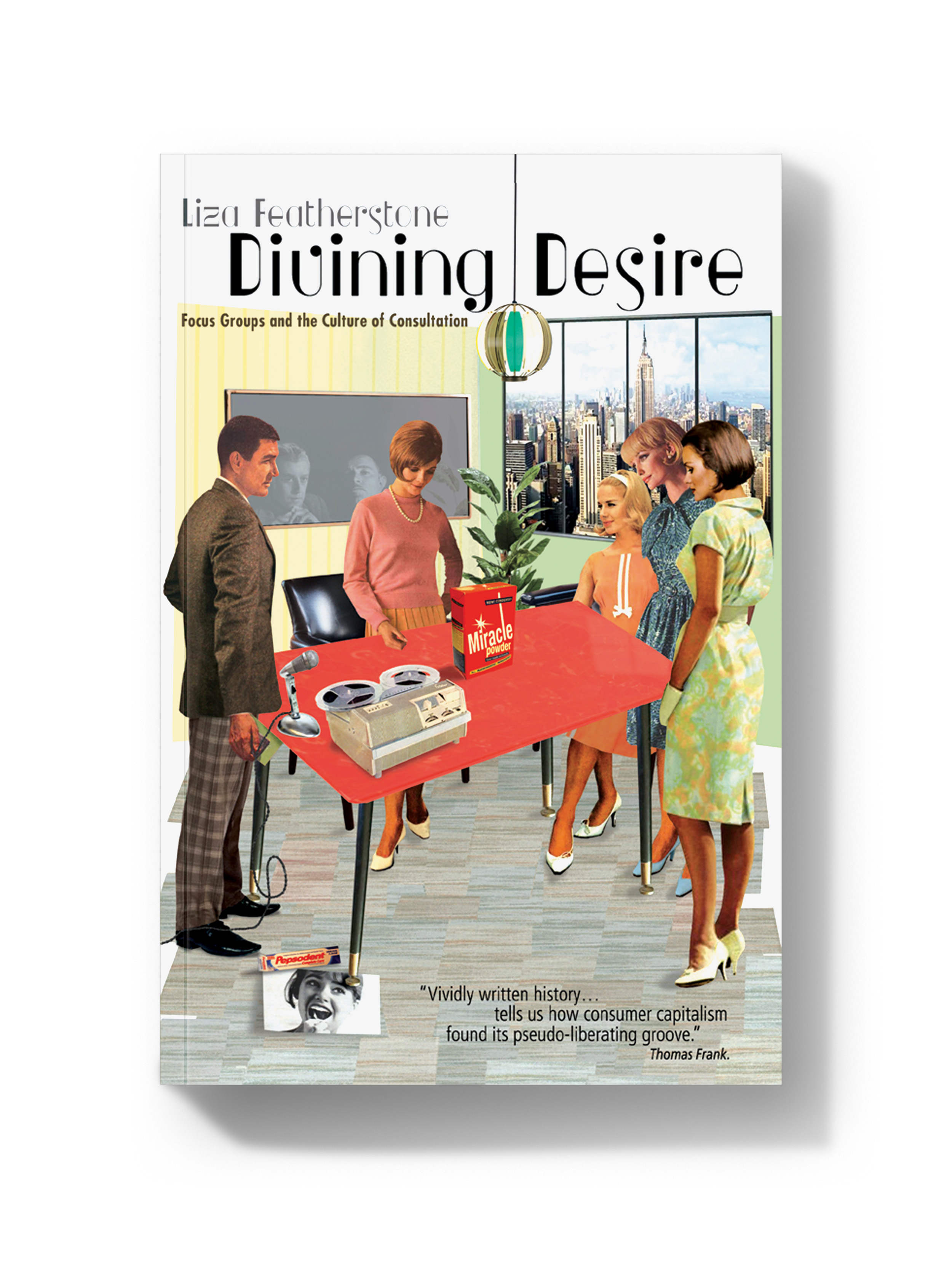

(Photo: OR Books)

Divining Desire: Focus Groups and the Culture of Consultation

Liza Featherstone

OR Books

Every day, all across America, small groups of strangers gather in nondescript rooms. Under the guidance of professional moderators, these strangers “focus” their feelings on paper plates, vodka advertisements, movie endings, and political sound bites. Microphones in the room record everything said for future review. Often, the people funding the meetings, whether paper-plate manufacturers or political campaign consultants, are watching live through one-way glass, hungry for glimpses of how “real people” think.

In her fascinating new book, Divining Desire: Focus Groups and the Culture of Consultation, the political writer Liza Featherstone uses these interviews as a lens on the past, present, and future of the American project. It’s a difficult book to pin down: part history of focus groups; part embedded journalism about focus-group participation; part analysis of the social discourse about focus groups, which so many Americans love to hate. Before I started reading, I assumed that Featherstone—a longtime leftist critic of corporate America’s encroachment on our daily lives and political processes—would hate them too. But she’s up to something more complex, and more interesting.

The focus group began crystallizing into an American institution during World War II, when Columbia University sociologists were recruited to help sell war-skeptical Americans on the idea of fighting Nazis. At first, these sociologists used group interviews to save time and money. But they quickly realized that group dynamics often made it easier, even enjoyable, for people to dig deeper than they did in one-on-one conversation. After the war, group interviewing was repurposed to new ends: figuring out what consumers across the country were willing to spend their money on, and why. The fate of post-war capitalism hung in the balance (or so some thought). Market research exploded and, during the 1980s, returned to political discourse with a force, as a burgeoning class of political consultants deployed Madison Avenue research and messaging techniques in the service of candidates and policy platforms.

The idea of asking what people want before trying to sell them something is, on its face, completely sensible. But America has always had an ambivalent, uneasy relationship to market research; Divining Desire is at its best when exploring this unease. In 1957, the journalist Vance Packard had a smash hit with his book The Hidden Persuaders, a panicked indictment of market research as a predatory force that used creepy psychological techniques to manipulate the unsuspecting consumer. This same suspicion is commonplace today, modified slightly by ambient awareness of the networked focus groups to which our promiscuous Internet cookies contribute nonstop.

In politics, especially, the focus group is a signifier of disconnect and inauthenticity: Politicians, we suspect, use them in lieu of developing their own principles or intuitive sense of what their constituents want and need, or how the people they claim to represent actually speak about their lives. These sentiments are so widespread that publicly denying your use of focus groups has long been an easy way to broadcast your realness. “I can assure you, I’m not going to make any decisions in regard to anybody’s life based upon a poll or a focus group,” boasted George W. Bush, the self-proclaimed Decider-in-Chief.

(Photo: Jarren Vink/Pacific Standard)

Featherstone is certainly aware of the nefarious potential of market research. Profit-mad companies use focus groups to boost sales of products they know to be dangerous; duplicitous politicians use them to rally the support of working Americans for policies that make their lives less stable. Like much of what happens on the Internet, she argues, focus groups make participants feel listened to but give them no real power, conjuring the impression of democracy without giving people any more control over their lives.

Despite these concerns, Featherstone spends a considerable amount of space, if not exactly proselytizing for focus groups, then at least defending them from their most prominent critics. Because it’s not just the hoi polloi made uneasy by focus groups. Our elites hate them too. Featherstone documents a rich tradition of executives and their favorite thinkers heaping disdain on the very idea of listening to what potential customers have to say. Steve Jobs often railed against focus groups, insisting that Apple had no use for them because “it’s not the consumers’ job to know what they want.” Malcolm Gladwell tells his audiences—especially at his lucrative corporate speaking gigs—that focus groups generally fail. Elites and would-be elites eat up denunciations of the fickle, unimaginative consumer, and pass around well-worn stories of expensive failures like the Ford Edsel and New Coke, satisfied that these prove the folly of focus groups—despite ample evidence that, in each instance, other factors were, in large part, to blame.

“Hostility to focus groups,” Featherstone writes, risks becoming “a populism of fools—which really looks more like elitism.” Focus groups are merely a symptom of an America where business and political leaders know little about the Americans whose dollars and votes they’re chasing. By confusing the symptom with the disease, we risk missing what focus groups have to tell us—not about flat vs. ridged potato chips, but about American democratic impulses.

Attending focus groups herself—on Juicy Juice, train travel, and personal finance, among others—Featherstone realizes, like many observers before her, just how hungry people are for the sense, however fleeting, that someone is really listening to what they have to say, in a relatively un-rushed setting where others are sharing and being listened to as well. On a good day, maybe they’re even making some consumer product better, more helpful. Some participants, of course, are just in it for the money: A significant percentage, Featherstone learns, habitually lie about their lives to sneak into as many groups as possible, maximizing their participation fees. Often, these infiltrators are abetted by group recruiters who, eager to fill seats, nudge them toward the most advantageous answers.

In these details, and with help from Featherstone, we can hear a focus group speaking truths despite itself— telling us something important about our desires for connection through conversation, and our impoverished options for finding it. All parties involved know the conversation is a sham of sorts; the elites may not always care, but the rest of us want more.

Or at least some of us do. “I do focus groups,” said Donald Trump in 2015, using his thumbs to point to his brain, “right here.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the December/January 2018 issue of Pacific Standard.