You just can’t keep a creepy clown down. It, the first feature-film adaptation of Stephen King’s sprawling 1986 opus about a group of Maine middle-schoolers who must face their greatest fears in the form of a floppy-shoed foe, has broken box office records for the horror genre, making $123.1 million at the United States box office in its opening weekend. That’s more than Wonder Woman—the highest-grossing movie so far of 2017—made in its opening weekend ($103.1 million) and only slightly less than the latest addition to the Star Wars canon, Rogue One ($155 million). It’s an unlikely success story, considering that cinema attendance this summer was at a 25-year low.

In addition to many other reasons for its success—a trailer that broke viewership records, a genius marketing strategy, the fact that clowns remain forever terrifying—King’s story is clearly still resonating with audiences 31 years after it was published. And like any good work that’s managed to stay in the mainstream canon, It has inspired plenty of analysis, much of it on the lingering horror in King’s clown or the novel’s lasting critique of American amnesia about childhood.

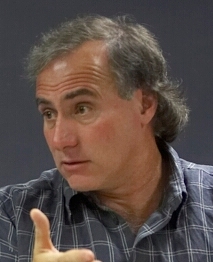

So why does It remain so scary? For an answer, we turned to Anthony Magistrale, an English professor at the University of Vermont and scholar of King books and adaptations. Magistrale, the first author to ever pen a scholarly work on Hollywood adaptations of King, has written over a dozen works on the novelist. As for It, he’s previously argued King’s opus portrays how a community can institutionalize child abuse—”Pennywise’s [the clown’s] actions merely reflect the town’s general indifference toward its children,” he wrote in his 2009 book Stephen King: America’s Storyteller.

In a conversation with Pacific Standard, Magistrale discussed the central thesis of It, and explained what images of children running around town without supervision mean in an era of helicopter parents and “stranger danger” PSAs. Warning: There are spoilers ahead.

Tell me a little about your original interest in the 1986 It, and, in your own words, your conclusion about the story that you penned in Stephen King: America’s Storyteller.

It, coming as it does pretty much in the middle of King’s career, is both a summary and a recapitulation of some of King’s major themes that have appeared until that point. It speaks to King’s attitude toward the gap that exists between children and adults. That gap is clearly demarcated: The children in his fiction, prior to and including It, are victims of child abuse and adult negligence. Because the adults are preoccupied with issues such as drug and alcohol addiction, [there is] a kind of willful indifference to children who are both their biological children as well as their community’s children. Children are left to create alternative relationships with other children or with surrogate fathers.

It speaks to those issues. It’s a very depressing book, but it has extreme moments of hopefulness in it too. The depressing part of It is the social system that King portrays within the Derry community, which is a simulacrum for Bangor [in Maine, where King wrote It]. The hope comes in terms of the children being able to create not only a bond with one another, but also a kind of Wordsworthian hopefulness and the connection that they make back to their childhood as adults. It says that the only way that children can survive is by keeping in contact with this kind of Wordsworthian former self that’s part of being a child. In other words, that the adults must not lose contact with what it is to be a child.

There’s a very important moment in the novel where one of the main characters, Ben Hanscom, comes backs to Derry as an adult and looks at a library, where the adult section and the children’s section are connected by a lit, glassed-in corridor. That’s a little heavy-handed, but it’s the metaphor for the novel: If you don’t maintain that connection between adulthood and childhood, then you’re doomed to maintain the chasm that separates both.

You mentioned that Derry was a simulacrum of Bangor, Maine, which is where King moved to write this novel. In what ways was It a product of its time when the book was released in 1986?

It was the end of an era where children were allowed to run free. After this novel, American attitudes toward childhood began to get more ossified: In other words, we’ve become far more paranoid and protective over children. One of the things that happened in the novel as well as in the film is that the kids are allowed vast amounts of time to not be under adult supervision. I see that as changing, and some of that has to do with the advent of the video game, and multiple screens and the Internet, but also telephones and cell phones. That tends to keep children contained. [Video games] may be violent alternatives to going out and playing, but they’re certainly something that doesn’t worry helicopter parents, who are paranoid, especially post-9/11, about all sorts of things that run rampant in this culture, everything from drugs to terrorism to kidnapping.

Hollywood has been trying to make an It film adaptation for the last eight years. What is it about this story that is resonating again now?

(Photo: University of Vermont)

Why is It coming about now? I think they finally figured out what to do with this rambling opus—make it something that was truly terrifying. Its relevance is that we are a paranoid nation, and that paranoia translates really beautifully within this novel, from the need for curfews to the danger of children just playing. Look at the level of surveillance and fear that has dominated our culture since 9/11. This is not an accident.

In addition to the paranoia in the book, you’ve described how its horror stems from the systemic abuse of children in its setting. Do you think there’s a larger awareness of child abuse than there was in the ’80s?

I think so. Just look at the way in which the Catholic Church has undergone scrutiny that it never underwent before: It’s only been within the last 20 to 25 years that perpetrators have been held accountable. People who have done their best to keep pedophilia a secret—and I’m speaking especially of the clergy here, and those that are in charge of the clergy, like monseigneurs and bishops—are finding themselves in terrible trouble, because they were allowed to get away with this. That’s not so prevalent anymore.

Something that was interesting to me as well in the new movie was that its images evoked other kinds of systemic inequalities: The many shots of gutters reminded me of the Flint Water Crisis, and Henry Bowers’ police officer father, who abuses him, brought to mind unjust policing tactics. The movie puts a new spin on certain elements, and more emphasis on bits that will resonate now. If you read the book now, does it hold up as much?

I really do think it does hold up. There are some universal elements to it. I also think we’re also dealing with an era where a lot of people are finding themselves stressed. They were probably stressed in the ’80s as well, it was after all the age of Reagan, after all, with an emphasis on the family and on conservative values. But what’s changed since the ’80s is the impulse that has led to the election of people like Trump. There’s huge income inequality that is part of American culture now that wasn’t the case in the ’80s. This has created a kind of tension within American culture that speaks to—again—issues like drug abuse. How do we define the opioid problem in this country right now, if we don’t talk about it in terms of class differences?

The fact still remains that we’re talking about a culture that is not at home with itself—that has a superficial patriotism that’s at work, but doesn’t have safety nets. The gap between rich and poor, and liberal and conservatives have grown further apart since 1986 and have become more aggressive and antagonistic.

I’ve always looked at King as a sociological barometer. If he’s going to be remembered 100 years from now, this is how he’s going to be remembered: as somebody who was very capable and very adroit at talking about the anxieties and tensions of end-of-the-20th-century America.

2017 will see even more Stephen King adaptations than usual: In addition to It, we’ve got the release of The Dark Tower, Children of the Corn: Runaway, Gerald’s Game, and 1922. Why is Stephen King having another moment this year?

Well, there’s been a little gap: There haven’t been a lot of King films in the last 10 years; it’s been quiet. And I think filmmakers and screenwriters have been working on his stuff. The last time I interviewed [King], he talked about wanting to direct Gerald’s Game himself. The fact that he isn’t, I think, is a good idea: I think King is best appreciated as the wellspring from which other artists can work. The perfect example is Shawshank Redemption, a novel that is very good that was turned into an absolutely brilliant film.

I think you’ve just had a build-up of work that has been in the pipeline for a long time. They’re variant films: You’ve got It coming from ’86, Gerald’s Game coming from the mid-’90s, and The Dark Tower essentially culminating in the 21st century. But it really began in the ’70s with The Gunslinger. So you’ve got this build-up of all of King works, and they’re finally coming out to greater or lesser degrees. It sounds like It is going to be one of the great masterworks of his adaptations [but] The Dark Tower sounds terrible. And another Children of Corn? Shoot me first.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.