On Tuesday, President Donald Trump defended his comments made over the weekend in which he blamed “many sides” for the violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, that led to three deaths.

“What about the alt-left that came charging at the alt-right?” Trump asked reporters at Trump Tower, in response to criticisms of his failure to quickly condemn white nationalist groups. Trump claimed that he had watched the protests “much more closely than you people watched it,” and that counter protestors had also become “very, very violent.”

“You had a group on one side that was bad. You had a group on the other side that was also very violent,” Trump said. “Nobody wants to say that. I’ll say it right now.”

Trump is hardly the only person to raise concerns about the “violent” or “radical left.” Conservatives have long pointed the finger at left-wing groups like antifa for disturbing otherwise peaceful protests and pro-Trump rallies. And it’s certainly true that antifa embraces violent tactics, as Peter Beinart wrote recently in The Atlantic:

Since antifa is heavily composed of anarchists, its activists place little faith in the state, which they consider complicit in fascism and racism. They prefer direct action: They pressure venues to deny white supremacists space to meet. They pressure employers to fire them and landlords to evict them. And when people they deem racists and fascists manage to assemble, antifa’s partisans try to break up their gatherings, including by force.

But Trump’s comments downplay the fact that it was not a member of any left-wing group, but rather a white supremacist, James Alex Fields Jr., who drove his car into a crowd of counter-protestors on Saturday, killing one 32-year-old woman and injuring at least 19 others. Part of the problem is that the alt-right takes Trump’s false equivalence in this particular case as a pardon. As Senator Marco Rubio (R-Florida) pointed out on Twitter, “The White Supremacy groups will see being assigned only 50% of blame as a win.”

The #WhiteSupremacy groups will see being assigned only 50% of blame as a win.We can not allow this old evil to be resurrected 6/6

— Marco Rubio (@marcorubio) August 15, 2017

Indeed, David Duke, a former leader of the Ku Klux Klan, thanked Trump for his comments condemning “leftist terrorists” Tuesday afternoon.

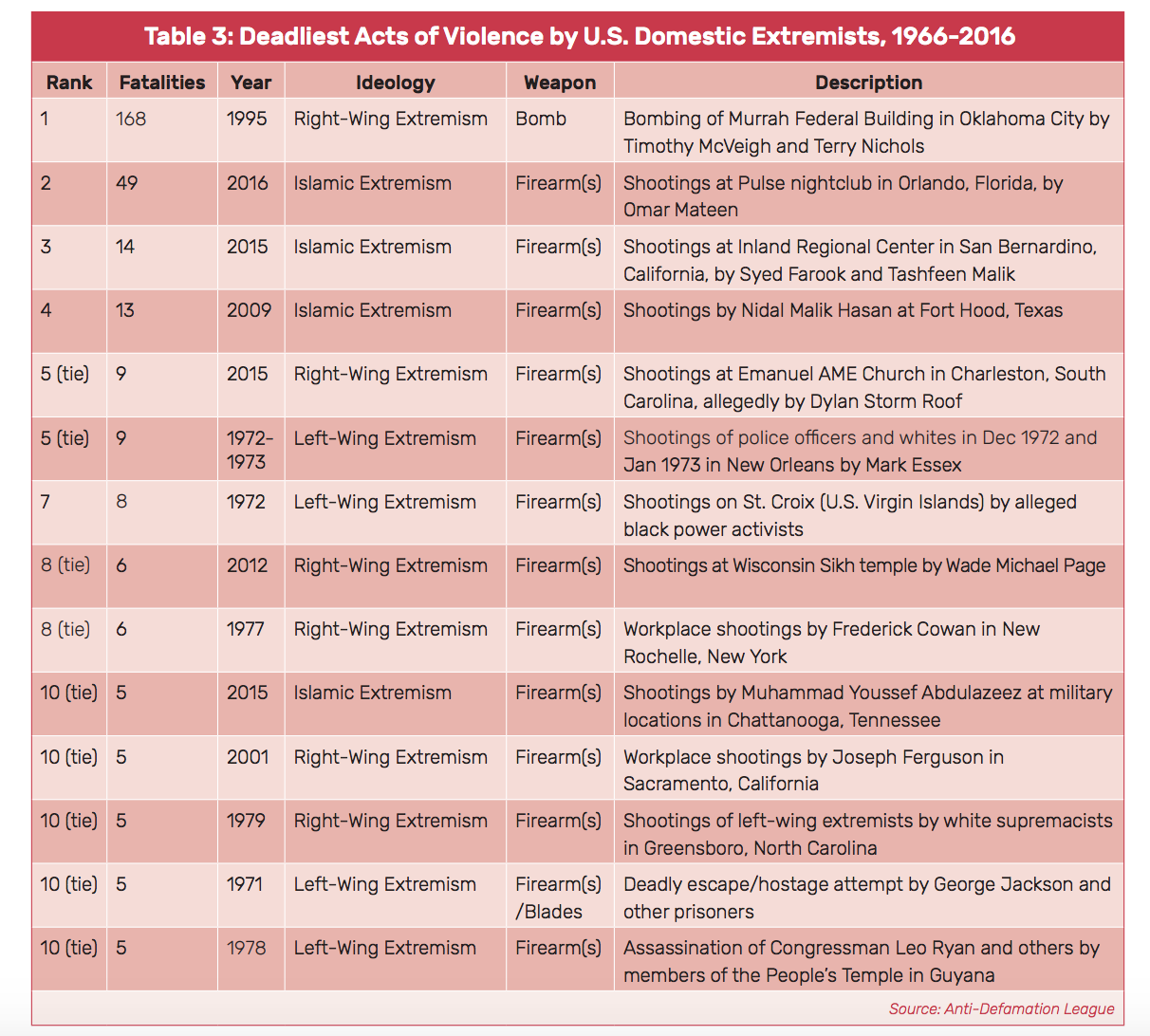

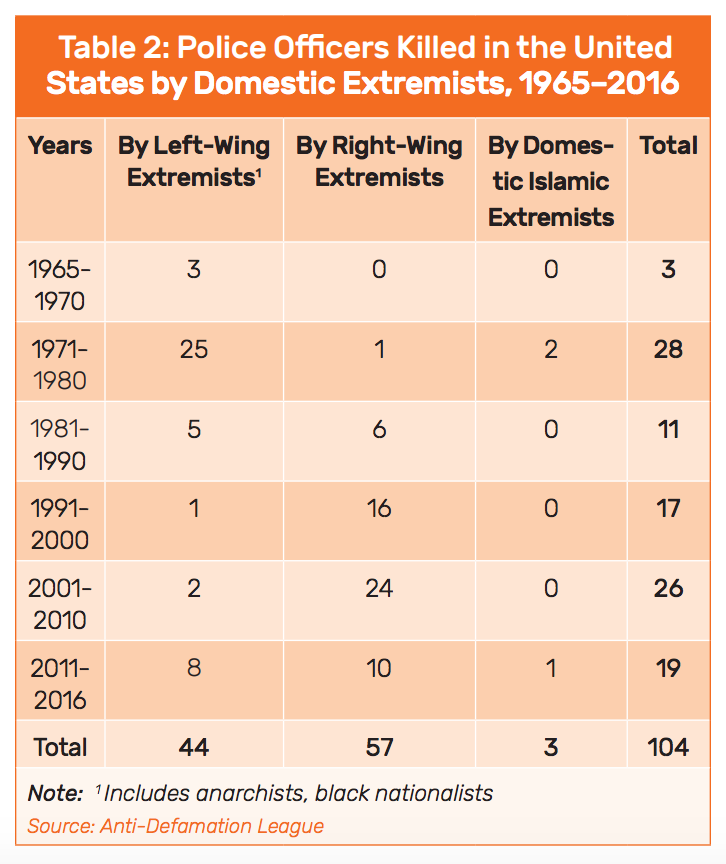

https://twitter.com/DrDavidDuke/status/897559892164304896And, generally speaking, right-wing extremists have been responsible for many more deaths than left-wing extremists since at least the 1970s, according to the Anti-Defamation League; over the last two-plus decades, white supremacists were behind 43 percent of right-wing terror incidents in the United States.

“In the past 10 years when you look at murders committed by domestic extremists in the United States of all types, right-wing extremists are responsible for about 74 percent of those murders,” the ADL’s Mark Pitcavage told NPR back in June, after a lone gunman opened fire on the Republican congressional baseball team.

But that doesn’t mean this pattern will continue to hold true; according to the ADL, increasing polarization and anger could lead to more eruptions of violence from both sides.

The baseball-team shooter, James Hodgkinson, was not associated with any left-wing extremist groups, whose members are typically more likely to engage in violent behavior than those who hold more mainstream, liberal, or conservative, views. “In the wake of the 2016 presidential election, ADL has been tracking growing anger within the American left, directed at President Trump, his administration and political allies,” Oren Segal, of the ADL’s Center on Extremism wrote in June. “In recent months, ADL has been warning law enforcement personnel about the possibility of an increase in left-wing violence as a result of the growing anger. The shootings in Alexandria appear to be an example of this.”

And, to be sure, violence appears to be rising among far-left extremists: A 2016 report from the ADL shows that left-wing extremists killed more police officers between 2011 and 2016 than any other time since the 1970s.

In other words, extremists on both ends of the political spectrum are certainly capable of violence, but it’s worth noting that violent means rarely lead to their desired end. As Michael Fitzgerald pointed out in Pacific Standard in March, while non-violent protests tend to succeed more often than not, violent insurgencies end in failure 75 percent of the time.